Eurozone, European crisis & policy responses

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Goldman Sachs Global Macro Conference - Asia 2011, Hong Kong, 22 February 2011

1. Introduction [1]

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a pleasure to have the opportunity to speak at this distinguished gathering here today.

We are certainly living in ‘interesting times’, as the Chinese say. Slightly ‘too interesting, for too long’ I would add. Over the past few years, we have all witnessed a global financial crisis, which has caused profound changes in the outlook for the global financial system and global economy.

This morning, I will focus on one manifestation of the broader financial turmoil: the sovereign debt crisis experienced by some euro area countries. In my remarks, I will first discuss the origins of this crisis, and then draw some comparisons with the emerging market experience – particularly in Asia. After reviewing how the European authorities have responded to the crisis, I will conclude with some remarks on the outlook for the euro area. While we certainly face considerable challenges at present, I am confident that Europe will emerge stronger from the current episode, not least because some of the existing gaps in the institutional framework for Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) will be filled. In the end, this will make the whole structure more stable and robust.

2. Origins of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe

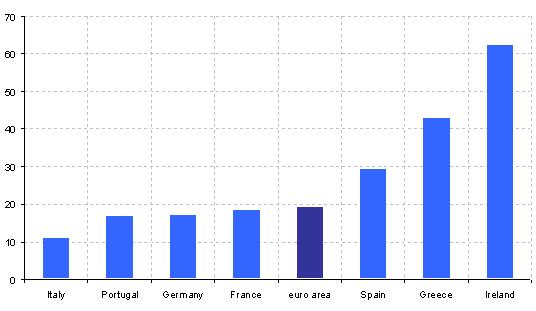

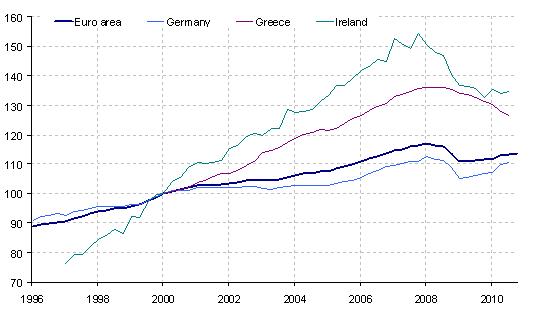

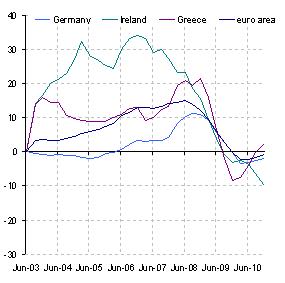

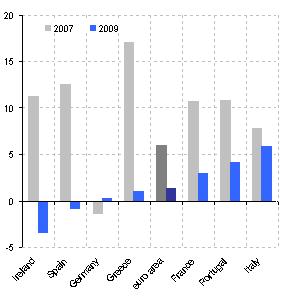

It is striking that those countries which experienced the European sovereign debt crisis in 2010 – notably Greece and Ireland – were among the best performers in terms of growth in economic activity within the European Union (EU) over the decade preceding the crisis (charts 1 and 2). Indeed, Ireland was called the ‘Celtic Tiger’, drawing a parallel with the fast-growing ‘Asian Tigers’ in earlier decades.

While prima facie a paradox, the relationship between strong pre-crisis growth and the severity of the crisis itself reveals much about the origins of the underlying economic, structural and institutional weaknesses that lie at the heart of recent events.

The introduction of the euro in 1999 led to a sharp fall in real interest rates especially in the so-called peripheral countries of the euro area, as nominal interest rates converged to low German levels (Chart 3). In addition, the credibility of monetary policy’s commitment to maintain price stability was bolstered by the institutional changes associated with Monetary Union (Chart 4). The resulting improvements to the growth outlook were further supported by the completion and deepening of the EU Single Market and the prospect of structural reforms underpinning national competitiveness in this integrated market.

In this context, the outlook for income growth in the peripheral countries was widely believed to have been transformed for the better. As a consequence, demand for credit expanded rapidly: households and firms in the periphery sought to borrow, so as to reap the available growth opportunities via investment and enjoy the benefits of prospective wealth gains immediately.

This surge in the demand for borrowing was met with a relaxation of the credit supply (Chart 5). Financing conditions eased significantly as real rates fell. Country risk premia diminished, as peripheral countries adopted a credible and stable currency. Spreads between government bond yields of euro area countries narrowed to very low levels. Financial institutions could borrow more easily abroad, as currency risk diminished. Deeper and more integrated capital markets facilitated greater opportunities for cross-country diversification. And greater competition spurred rapid adoption of financial innovations, with securitisation and risk transfer markets playing an important catalytic role in expanding the loan supply. [2]

Credit growth surged dramatically. No doubt part of the rapid expansion of credit was justified on fundamental grounds. After all, studies by the European Commission during the 1980s and 1990s had promised a sizable growth dividend from the Single Market and Monetary Union. [3] But, in an environment of large-scale structural change in peripheral economies and their financial systems, distinguishing the impact of improved fundamentals from that of ‘bubble-like’ behaviour proved a formidable challenge.

Indeed, with the considerable benefit of hindsight, there can be little doubt that a significant component of credit growth served to create and nourish financial and economic imbalances that have ultimately proved unsustainable, most notably in the housing market. Where mortgages had once been scarce or expensive, they became cheap and readily available. House prices boomed (Chart 6). Institutional and psychological factors fuelled an asset price bubble in real estate.

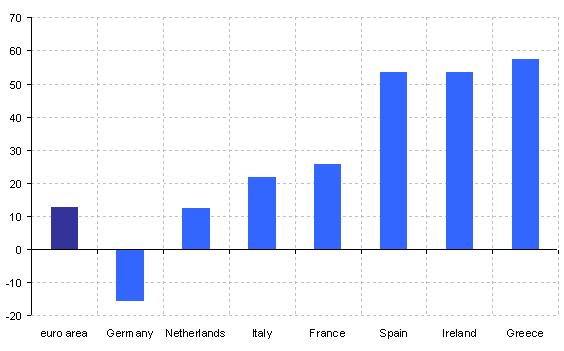

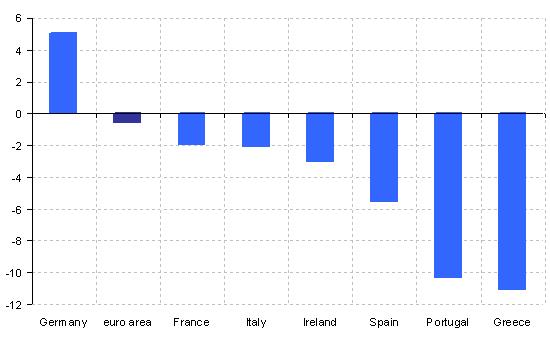

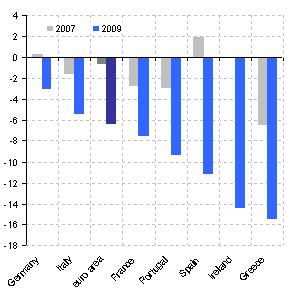

Supported by the dynamism of the real estate market, the peripheral economies grew rapidly. But the growth achieved was not balanced: sectors of the economy associated with the housing boom – construction and financial services – grew disproportionately (Chart 7), drawing resources away from other activities, raising concentrations in loan books and increasing macroeconomic vulnerability to sector-specific shocks. Rapid economic growth led to increased demand for imports, while strong wage growth put pressure on the price competitiveness of the tradable sector. Large deficits on the current account of the balance of payments therefore emerged (Chart 8). Inflows of financial capital from abroad – the proverbial ‘hot money’ – were needed to finance the current account deficit.

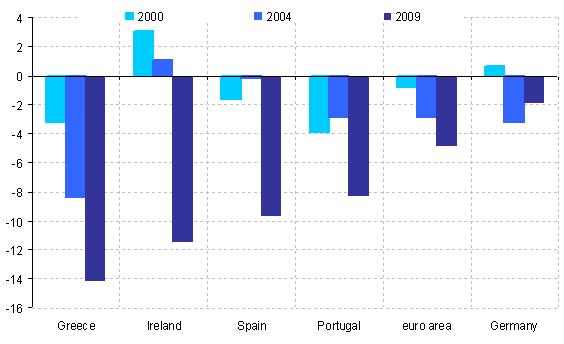

Such unbalanced growth also had important consequences for the fiscal accounts (Chart 9). The housing boom (and its positive impact on broader economic activity and spending) increased tax revenues, dramatically in some cases. These ‘windfall’ increases in tax revenue were treated as structural rather than cyclical in nature, as the housing boom was prolonged and appeared to survive the cyclical weakness in activity in mid-decade. [4] In Greece, tax windfalls allowed successive governments to obscure a fundamental weakness in the fiscal system, which was only later revealed when the public accounts statistics were improved. In Ireland, the windfalls supported the implementation of a pro-cyclical fiscal policy, as governments used revenue strength to justify tax reductions and higher public spending. Massive implicit liabilities towards the financial sector were accumulated as banking sectors grew rapidly.

Ultimately, the real and financial imbalances created by these dynamics proved to be unsustainable. The global financial crisis in 2007-08 was the crucial triggering event (Chart 10). First, the onset of global recession led to a deterioration in growth performance, rendering the fiscal and financial burdens imposed by past behaviour unsupportable. Second, the financial tensions led to a disruption of domestic financial intermediation, with severe consequences for both private and public financing.

In Greece, the banks – which were reasonably strong in a ‘stand-alone’ sense – were undone by revelations about the weakness of public finances. In Ireland, causation ran in the opposite direction: the bloated and failing domestic banking system imposed an intolerable burden on what, prior to the crisis, had been a superficially strong fiscal position. Regardless of the causation, the consequences were the same: as confidence eroded, the inflow of foreign capital dried up. Subject to a ‘sudden stop’ in external financing, [5] the European sovereign debt crisis – itself inextricably linked with problems in the financial sector – erupted, forcing Greece and Ireland to seek financial assistance from the European Union and IMF.

3. What can we learn from the emerging market crises of the past thirty years?

The developments I have just described might give those of you living in emerging economies a sense of déjà vu. And indeed it has become commonplace to draw comparisons between recent events in Europe and the periodic financial crises seen in emerging market economies (EMEs) over the past three decades: Latin America’s debt crisis in the 1980s; the Mexican tequila crisis of 1994; the Asian financial crisis in the second half of the 1990s; and the Argentine crisis of 2001.

Extensive economic literature has analysed these events and identified important roles for many of the phenomena I have just described. [6] It is therefore useful to explore parallels between the emerging market experience and what we are currently seeing in Europe. Here in Hong Kong, it is natural to focus on the Asian experience in the mid- to late-1990s, although events in Latin America are also useful to bear in mind.

To set the stage for a discussion of policy responses, allow me first to set out what I see as the key similarities and key differences between these episodes.

Similarities between euro area and EME experiences

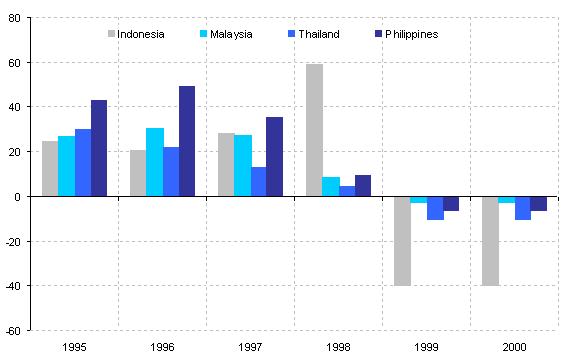

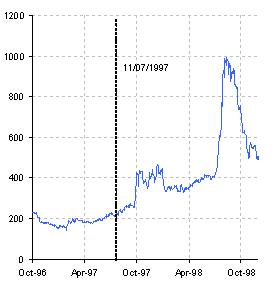

The accumulation of financial imbalances and vulnerabilities prior to the crisis is an important feature of both the European and Asian experience. Over-optimistic expectations of longer-term growth performance stimulated a surge in credit expansion and economic activity, associated with massive inflows of capital from abroad (Chart 11). [7] The risks associated with these capital inflows were under-appreciated by investors and therefore under-priced by markets, in part because the aggregate and systemic consequences of a ‘sudden stop’ in such flows were neglected in the decisions made by individual investors (Chart 12). Rating agencies acted in a pro-cyclical manner, also failing to adequately assess systemic risk (Chart 13).

The inflationary consequences of strong growth led to a loss of competitiveness, as the real exchange rate appreciated (Chart 14). The current account of the balance of payments shifted into deficit, creating a dependency on the inflow of foreign capital (Chart 15). [8] And the rapid pace of economic growth obscured the underlying weakness of public finances, in some cases abetted by creative accounting practices, such as shifting government liabilities off the balance sheet.

The case of Ireland seems particularly close to Asia’s experience in the 1990s: while public finances appeared relatively strong, a vast external debt was being accumulated by the banking system. The implicit government liabilities towards the financial sector arising from deposit insurance schemes and the need to manage systemic risks were neither fully recognised nor appropriately priced (Chart 16).

By contrast, the Greek experience appears closer to that of Latin America. In these cases, fiscal indiscipline, in part initially obscured by creative accounting practices, lies at the heart of the accumulation of financial imbalances, rather than a build-up of external debt on bank balance sheets. Argentina’s crisis in 2001 is a case in point, although the experience was shared by many Latin American countries in the 1980s (Chart 17).

A further important similarity between the emerging market experience and that of the peripheral euro area countries is that the external debt is denominated in a currency which the national authorities do not completely control. In emerging markets, so-called ‘original sin’ – that is, a lack of credibility created by poor macroeconomic discipline in the past – implied that external debt was overwhelmingly denominated in US dollars. [9] In the euro area, debt is denominated in euros. Although this is obviously the currency of euro area countries, the single monetary policy aims at price stability across the euro area and thus cannot take account of national priorities deriving from fiscal or financial weaknesses in peripheral countries.

By implication, neither in the emerging markets nor in the euro area periphery can the real value of the external debt burden be eroded by inflation or devaluation. Any attempt to devalue would simply raise the domestic burden of the external debt. Of course, this was precisely the point: by issuing debt in a currency which they could not control, the national authorities in the euro area ‘tied their own hands’. Before the crisis, they obtained a credibility gain that would lower overall funding costs and thus reduced the probability of a crisis. But when a crisis occurs, the external value of the debt burden cannot be reduced by devaluation.

Differences between euro area and EME experiences

While many of the experiences of the euro area periphery and the EMEs are similar, there are also important differences.

First, in general terms, Europe is more advanced both economically and institutionally than Asia (even if there are notable exceptions, such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Korea). [10] Advanced economies have higher ‘debt tolerance,’ because of their stronger institutions, a more favourable composition of debt and a more stable fiscal revenue base (less dependent on a small set of goods, such as commodities).

Thus while the dynamics of financial crises may be similar, the level of debt at which they occur may be different. Of course, this can be a mixed blessing. The ability to accumulate more exposures may permit the pre-crisis boom to last longer. But it may also mean that the subsequent downfall is deeper.

The second difference is that, by having a national currency, even if it is rigidly pegged to an external anchor, as in the case of Argentina’s dollar currency board prior to 2001, the EMEs retain scope to devalue. By contrast, the European periphery countries have adopted the euro; they no longer have a national currency and therefore can no longer devalue, at least against their main trading partners within the euro area. Ruling out devaluation has pros and cons.

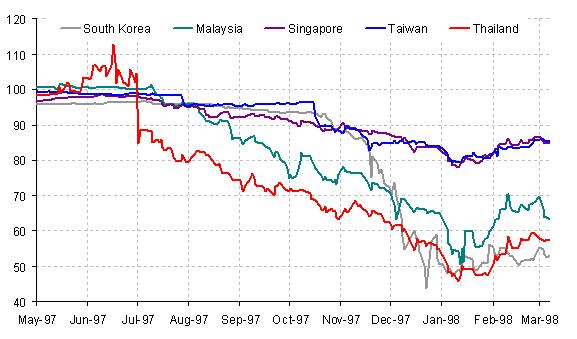

On the one hand, the eradication of devaluation risk eliminates one element of financing costs that may rise rapidly in a financial crisis, even if the currency risk simply morphs into a credit risk. Moreover, ruling out devaluation avoids ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ competitive devaluations that can trigger trade wars and protectionism, and weaken the growth outlook (Chart 18). And, without a devaluation option, peripheral euro area countries cannot fall into a vicious debt-devaluation spiral. Devaluation increases the real value of the outstanding foreign currency-denominated debt burden in domestic currency terms and may thus worsen the economic and fiscal outlook of a country under stress. Any resulting loss of market confidence may trigger further weakening of the domestic currency, thereby exacerbating the problem and creating a steady downward spiral of devaluation and rising debt burden.

On the other hand, devaluation offers some scope to improve external price competitiveness and thus boost growth via better export performance. The benefits of any such devaluation will be greater for countries that have an export-based model of economic growth, relying on price competitiveness to build market share. This is typical of the ‘Asian Tigers’, but may be less relevant for mature European economies where export performance is driven by other factors, such as quality or branding. For peripheral euro area countries, which cannot devalue, the way to improve competitiveness is via domestic wage restraint and structural reforms to boost productivity. In an environment where domestic debt overhangs are large, the former approach runs the risk of creating a debt-deflation spiral: domestic nominal incomes are driven down, while the nominal debt remains unchanged, thereby increasing the real burden of previously accumulated financial imbalances. [11] Yet Europe’s sovereign crises have erupted in the context of a worldwide recovery, led by strong growth and a potential for inflationary pressure in the emerging markets. Such a situation contrasts with the global disinflationary environment of the Latin American crisis in the early 1980s, and the cyclical slowdown affecting Asia in the mid-1990s. Because of the inflationary pressure in some of their many export markets in the emerging world, euro area countries are more likely to regain price competitiveness now than other crisis-hit countries were in the past.

The third difference between the euro area and the EMEs is that European countries generally have more sophisticated domestic financial markets than was the case during the Asian financial crisis. In particular, government debt plays several important roles: sovereign yields are the basis for the pricing of many other instruments; government bonds are widely used as collateral in private repo markets; and public debt is an important asset in the balance sheets of domestic banks and the wealth holdings of the private sector. As a result, euro area countries cannot afford to implement a sovereign default without suffering as a consequence of such a default a major breakdown of their financial, economic and social structure. There is no post-war example of a government in an industrialised economy restructuring its debt. For a euro area sovereign to seek to restructure its debt would be a huge leap into the unknown. This aspect is frequently omitted by financial analysts in their newsletters or by commentators or academics in their short op-eds. And this is the reason why they do not get the point right when they state that default and restructuring is unavoidable in the euro area.

The fourth difference is that, given the much greater depth and intensity of financial and economic integration in Europe, the strength of contagion across financial institutions and markets is potentially more significant within the euro area today than was the case in Asia in the 1990s. That is not to say that there was no contagion in the 1990s. But the cross-border exposures within the euro area are an order of magnitude greater than was the case for such intra-regional cross-holdings in Asian EMEs. This means that the potential for spillovers and a systemic area-wide crisis is much higher and has to be factored into the policy responses.

Of course, greater economic integration in Europe has been accompanied by greater institutional cooperation. Although now supplemented by the (still untested) Chiang Mai Initiative, the framework for economic policy cooperation in Asia involves less deep and intense collaboration than in the European Union. The single monetary policy in the euro area is the acme of Europe’s economic integration. And the situation in the 1990s in Asia was much less developed than now. Several Asian countries (notably Malaysia at an early stage) introduced capital controls in the face of the financial crisis, something which cannot be done in Europe given the depth of financial integration and the commitments made to the free movement of capital within the Single Market in the EU Treaties.

4. Policy responses to the crises

The much deeper set of economic and institutional linkages within the EU and euro area today compared with those that existed in Asia in the mid-1990s has important implications for the policy responses.

In particular, the lack of a regional framework in Asia placed the responsibility for addressing the financial crisis in the 1990s immediately and squarely on the international financial institutions, notably the IMF. By contrast, the close cooperation between EU countries has meant that the IMF has played a less prominent role in the recent crisis, even though it makes a significant contribution to the design and implementation of the adjustment programmes implemented in Greece and Ireland.

I am sure that the density of the EU framework of integration and cooperation has played a very positive part in tackling the crisis. Via both inter-governmental mechanisms (such as the European Financial Stability Facility, EFSF) and supranational initiatives (such as the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism, EFSM), the EU and its Member States have created an important source of external financial support for the domestic adjustment programmes introduced by Greece and Ireland. The availability of this support has also bolstered and underwritten consolidation measures implemented at national level.

The financing programmes have imposed strict conditionality on the recipient countries. They insist upon the implementation of essential measures, namely fiscal consolidation, financial sector restructuring and broader structural reform. While the EU is an equal partner with the IMF in imposing such conditionality, the EU countries that have provided financial support to countries in distress have insisted on IMF involvement because of the credibility this lends to the conditionality of the programme. Its involvement in Asia would be much more difficult. Note that the EU component of the financial support does not enjoy preferred creditor status – a situation unthinkable in other parts of the world. Given the depth of economic ties and trust between countries within the euro area, a sense of ‘common destiny’ is felt by all, leading to this exceptional level of support. As a result, creditors, in particular official creditors, are therefore more closely bound into the success of the programme and have a strong incentive to ensure that the programme’s conditions are fulfilled, thereby underpinning its success.

Aside from their role in fiscal consolidation, the European authorities have also offered support to the financial systems of the most adversely affected countries in the euro area. This has been done via EU/IMF programmes to support restructuring and recapitalisation of crisis-hit banks; and through ECB measures, notably its framework for ‘enhanced credit support’. [12] By introducing a variety of operational facilities, the Eurosystem has ensured that liquidity continues to flow to the peripheral countries, preventing a seizing-up of financing flows in those hardest hit and a significant disruption to the European financial system as a whole.

Indeed, one of the most important contributions made by the EU framework has been to ensure that the policy responses to the financial crisis have taken a sufficiently Europe-wide – or at least euro area-wide – perspective. Given that the responsibility for financial supervision and fiscal sovereignty remains at national level in the EU, at the peak of the financial crisis there was a natural tendency for Member States to resort to national solutions. A number of countries succumbed to this temptation, in the process imposing costly externalities on other Member States. For example, providing government guarantees for all bank liabilities in one jurisdiction prompted outflows of deposits from other jurisdictions, requiring similar guarantees to be offered elsewhere. This may have resulted in an overall level of intervention that was unnecessarily intrusive and undesirable in terms of the incentives created in the financial sector. In short, the existence of considerable externalities and scope for significant spillovers within a financially integrated region like the euro area may have led to individually reasonable actions resulting in a collectively inferior outcome.

Recognising these concerns, the EU institutions have stepped in to ensure that an area-wide perspective, internalising these externalities, is adopted. As we have seen, coordinating both public and private behaviour to achieve a favourable outcome in a multiple equilibrium setting requires both clear and credible programmes at national level, and support and coordination at EU level. After a somewhat hesitant start, the European Union is now moving towards a stronger institutional framework to support this approach.

Looking beyond the horizon of existing programmes, the crucial longer-term macroeconomic and financial discipline requires further institutional change and integration, notably an enhanced Stability and Growth Pact, and the introduction of a new and more effective system of macroeconomic surveillance across EU Member States. The creation of the European Systemic Risk Board to conduct macro-prudential surveillance and the three new European Supervisory Agencies for the financial sector also aims to improve the quality and coordination of financial regulation and supervision.

Having said that, the main responsibility for dealing with the weaknesses underlying the sovereign debt and associated banking crises remains at national level. It is important to recognise that the relevant EU Member States now fully understand and accept this. In contrast to the experience in Asia in the 1990s or Latin America in the 1980s, there is little attempt to blame the sovereign crisis on foreign investors. Responsibility cannot be shifted offshore: the countries most immediately affected know that they have to act.

With the support of the EU and IMF, these countries have embarked on ambitious programmes of consolidation and structural reform to correct their domestic financial and economic imbalances. As I have already said, the origins of the intertwined financial and sovereign crises lay in institutional and economic frailties in the most afflicted countries. It is mainly up to these countries to correct these weaknesses and cure the problem.

A key element of the resolution of the Asian crisis in the mid- to late-1990s was a deep and fundamental restructuring of the domestic financial sectors. This was implemented in what, at that time, was seen as a relatively abrupt manner. The conditionality imposed on IMF financial support was associated with the application of ‘shock therapy’ to Asian countries’ financial sectors: losses had to be written down immediately, banks were closed or sharply restructured and many institutions were sold to foreigners, arguably at ‘fire sale’ prices.

Within the euro area, various buffers – not least, the Eurosystem’s provision of liquidity support – have tempered the stresses in the financial system. This reflects the recognition that, within such a deeply economically and financially integrated region, ‘shock therapy’ adjustments may, through spillovers, weaken the financial system in other parts of the euro area. However, we must also ensure that such liquidity support to the banking sector does not delay or hinder the fundamental reforms required to address the underlying weaknesses the financial crisis has revealed.

In the end, the crisis-hit countries have no alternative: they have to make fundamental reforms to their banking systems, involving substantial restructuring and, in some cases, very significant downsizing. Liquidity support can help to reduce adjustment costs by smoothing the transition. But those costs should not be used as a pretext for delay.

5. Concluding remarks

Financial markets are testing the strength and resilience of the euro area and the willingness and ability of the euro area authorities to preserve the integrity and stability of the euro as a currency.

The institutional response to their challenge has been swift, strong and resolute. As regards monetary policy, the Eurosystem has implemented a set of measures that ensure the provision of liquidity to the euro area financial system, including to the banks of those peripheral countries that are currently subject to the greatest market scrutiny.

With respect to fiscal and macroeconomic imbalances, euro area governments are now strengthening the rules for fiscal and broader economic policy coordination. They have created and are refining facilities that can provide external financial support to those Member States facing the most intense pressures in sovereign debt markets. These developments aim to correct the deficiencies in the institutional architecture of Economic and Monetary Union exposed by the financial crisis. These facilities need to have sufficient resources as well as the flexibility to contain market pressures and coordinate the public and private sectors so as to achieve a sustainable and mutually beneficial outcome in an environment where several equilibria may be possible.

The Asian experience in the mid- to late-1990s demonstrates that radical reform can lead to a sustained recovery – one achieved largely without restructuring public debts. Indeed, one can argue that Asia has emerged from its financial crisis stronger than before: the institutional weaknesses which contributed to the build-up of financial fragilities, but were masked by high growth rates during the pre-crisis boom have been addressed.

Similarly, Europe will emerge from its current travails stronger if the weaknesses revealed by the recent financial crisis are properly identified and corrected through institutional innovation and reform. I am confident that this will be the case.

Seen from this continent, the recent crisis in European sovereign debt markets may be interpreted as a failure of the euro. But in Europe, the crisis is viewed differently. The problems we face today are the result of a flawed implementation of a fundamentally good idea. The bumpy ride of Economic and Monetary Union is largely the fault of the driver, not the vehicle. He has to learn from his mistakes and get some more practice – then he’ll be a better driver. As for the vehicle, it needs better brakes, for even the best of drivers can occasionally make mistakes.

Thank you for your attention.

| Chart 1: Real GDP per capita growth between 1997-2007 |

|

| Note: Growth rate shown in the chart is the percentage increase between 1997 and 2007.Sources: Eurostat and Haver Analytics. |

| Chart 2: Real GDP developments since 1996 |

|

| Note: Quarterly; 2000Q1=100.Source: Haver Analytics and Eurostat. |

| Chart 3: Ex-post real interest rates |

|

| Note: Series calculated as ten year benchmark bonds minus annual HICP inflation. Annual averages.Source: ECB staff calculations. |

| Chart 4: Break-even inflation rates |

|

| Note: Last observation refers to 14 February 2011. Daily.Source: ECB staff calculations. |

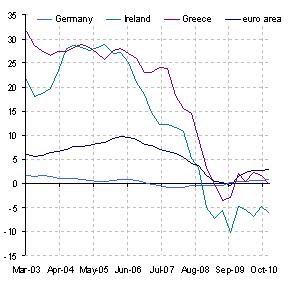

| Chart 5: MFI loans |

MFI loans to households – MFI loans to non-financial corporations   |

| Note: Last observation refers to 2010Q4. Quarterly; year-on-year % change; not adjusted for securitisation.Source: European Central Bank. |

| Chart 6: Real residential property prices in selected euro area countries |

|

| Note: Quarterly; 1998Q1=100.Source: Hiebert and Vansteenkiste (2010). |

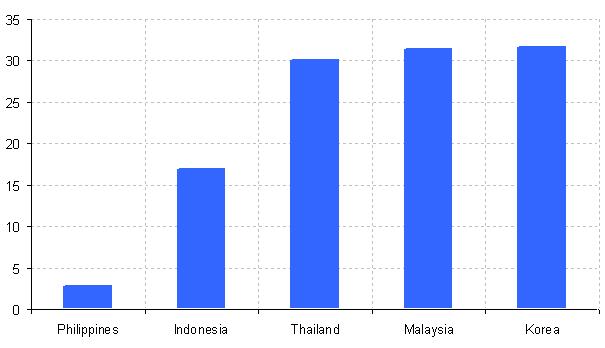

| Chart 7: Growth in real housing construction works between 2000-2007 |

|

| Note: Growth rate shown in the chart is the percentage increase between 2000 and 2007.Sources: Haver Analytics and Eurostat. |

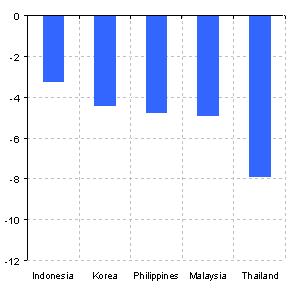

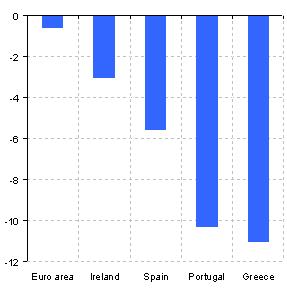

| Chart 8: Current account balances in selected euro area countries |

|

| Note: 2009; % of GDP.Source: Haver Analytics. |

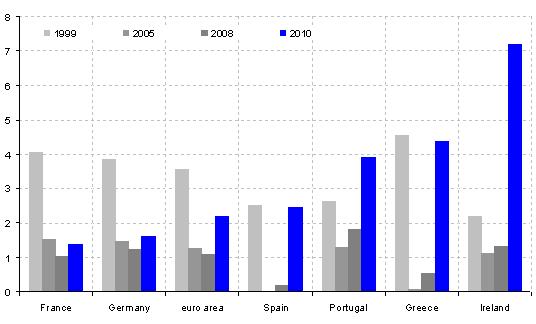

| Chart 9: General government budget balance in selected years |

|

| Note: % of GDP.Sources: Haver Analytics; European Commission. |

| Chart 10: Consequences of the global financial crisis |

Household credit growth (annual % ) – General government budget balance (% of GDP)   |

| Source: Haver Analytics, European Central Bank and Eurostat. |

| Chart 11: Credit growth to the private sector |

|

| Note: annual averages of monthly growth rates.Sources: Haver Analytics and IMF. |

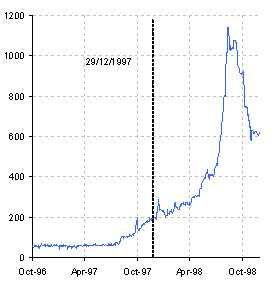

| Chart 12: EMBIG spreads in the run-up to the Asian crisis |

Philippines – Malaysia   |

| Note: in bp.Source: Haver Analytics and JP Morgan. |

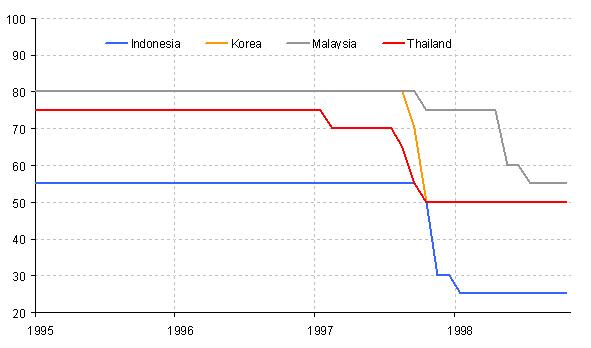

| Chart 13: Sovereign credit ratings of selected East Asian countries |

|

| Sources: Moody’s based on a linear conversion of the ratings (with Aaa equal to 100 and Caa equal to 5). |

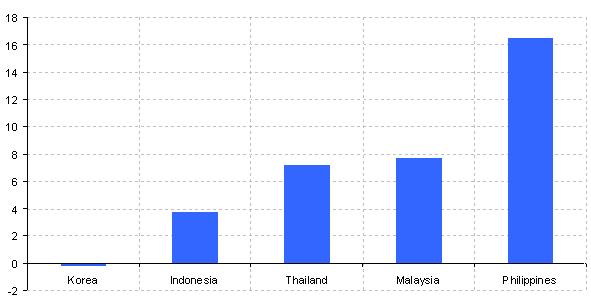

| Chart 14: Average estimated real effective exchange rate overvaluation as of late 1996 |

|

| Note: in percentage.Source: Average values by estimates of Chinn (1998), Goldstein (1998), Tornell (1998) and Berg and Pattillo (1998). |

| Chart 15: Current account balances in East Asia and the euro area |

East Asia (1996) – Euro area (2009)   |

| Note: % of GDP.Source: Haver Analytics. |

| Chart 16: Fiscal costs of recapitalisation as % of GDP |

|

| Note: high scenario.Source: IMF (1999). |

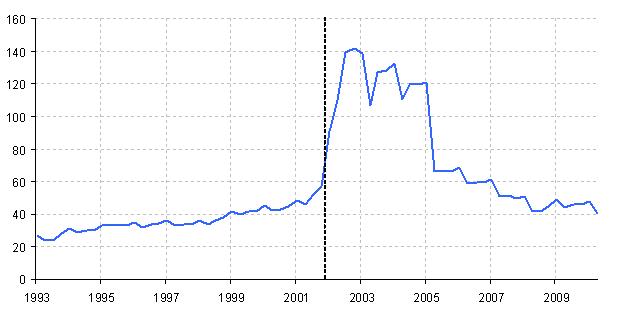

| Chart 17: Argentina public sector debt as % of GDP |

|

| Share of foreign currency denominated debt in 2001: 97.59% Source: Haver Analytics. |

| Chart 18: Exchange rates vis-à-vis the USD for selected emerging Asia countries |

|

| Note: 02/01/1997=100.Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors. |

-

[1]I wish to thank Huw Pill and Isabel Vansteenkiste for their contributions to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

-

[2]See: Altunbas, Y., L. Gambacorta and D. Marques-Ibanez (2009). “ Securitisation and the bank lending channel”, European Economic Review 53(8), pp. 996-1009.

-

[3]See: Cecchini, P. et al (1988). The European challenge 1992, Aldershot: Gower Publishing; and Emerson, M. et al (1992). One market, one money: An evaluation of the potential benefits and costs of forming an economic and monetary union, Oxford University Press.

-

[4]See: Morris, R. and L. Schuknecht (2007). “Structural balances and revenue windfalls: The role of asset prices revisited,” ECB Working Paper No. 737; and Kanda, D. (2010). “Asset booms and structural fiscal positions: The case of Ireland,” IMF Working Paper No. 10/57.

-

[5]See: Calvo, G.A. (1998). “Capital flows and capital market crises: The simple economics of sudden stops”, Journal of Applied Economics 1(1), pp. 35-54.

-

[6]The literature is too large to offer a complete list of references. For a summary, see: Edwards, S. (ed.) (2000). Capital flows and the emerging economies: Theory, evidence, and controversies, University of Chicago Press.

-

[7]See: McKinnon, R.I. and H. Pill (1997). “Credible liberalisations and overborrowing,” American Economic Review 87(2), pp. 189-193.

-

[8]See: Dornbusch, R., I. Goldfajn and R.O. Valdés (1995). “Currency crises and collapses,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2, pp. 219-293.

-

[9]See: Eichengreen, B., R. Hausmann and U. Panizza (2005). “ The pain of original sin”, in B. Eichengreen and R. Hausmann (eds.) Other people’s money, Chicago University Press, pp. 87-102.

-

[10]One measure of institutional quality is reported in the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Competitiveness Report.

-

[11]The classic reference is Fischer. I (1933). “The debt-deflation theory of Great Depressions”, Econometrica 1(4), pp. 337-357.

-

[12]Trichet, J-C. (2009). “The ECB’s enhanced credit support”, Address at the University of Munich annual symposium, http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2009/html/sp090713.en.html.

Banco Central Europeo

Dirección General de Comunicación

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemania

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Se permite la reproducción, siempre que se cite la fuente.

Contactos de prensa