Restarting a Market: The Case of the Interbank Market

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB,ECB Conference on Global Financial Linkages, Transmission of Shocks and Asset PricesFrankfurt, 1 December 2008

1. Introduction [1]

It is a great pleasure for me to speak tonight in front of such a distinguished audience. Tonight, I would like to share with you some concerns about the present state of financial markets, as some of these markets are not functioning properly or are barely functioning at all. Given the relevance of this issue at a global level, I find it quite interconnected with the topics addressed at this conference.

Markets exist for many goods - but not for all. There are many conceivable markets for goods and services that do not exist. Milton Friedman, for example, was famously puzzled by the absence of inflation-linked securities, although we have seen some developments since his times. I am sure each of us would be able to come up with other examples. Reasons for the incompleteness of markets may be related to the obstacles to setting up an environment for trade, such as transaction costs, network externalities in trading, costs related to legal enforcement, or more generally asymmetric information problems. It can happen that society would benefit from the creation of a new market, but that market forces may not be sufficient by themselves to overcome such obstacles. In these cases, the public sector can play a role in the starting of a market. These considerations are particularly pertinent for financial markets, which require significant technical infrastructure, where network externalities are very important, and where asymmetric information plays a paramount role. In fact, it is no surprise that stock market capitalisation and financial market development are an increasing function of institutional and legal development. [2]

I would like tonight to focus on a special activity in the field of market creation, which is the re-starting of a market which has stopped functioning properly. I consider as an example the interbank market. As you are aware, the functioning of the interbank market has been severely affected by the recent events in financial markets. While precise data on market activity are not available, as much of the money market activity (also in normal times) takes place over the counter, contacts with market participants indicate that the turnover, especially in longer-term segments of the money market, has decreased drastically.

Central banks have increasingly become intermediaries for interbank transactions, as witnessed by the steep increase in the size of their balance sheet (the size of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet, for example, has increased very significantly since the breakdown of Lehman Brothers). Especially since the introduction of fixed rate tenders with full allotment in the Eurosystem weekly open market operations, coupled with a narrower corridor for standing facilities, banks have been borrowing very large amounts in the Eurosystem open market operations and at the same time have significantly increased their recourse to the regular deposit facility offered by the Eurosystem. Trading with central banks has thus to a large extent replaced interbank trading.

Unusual as it may seem now, a financial system without a proper interbank market is not unprecedented. In fact, even in some euro area countries, full-fledged money markets came into existence only in recent decades. Also in Japan, starting in the middle of the 1990s, a weakening of the financial sector and a series of bank failures led to a breakdown of the interbank market, in some respects not unlike the situation we are facing today in Europe.

In such a context, there are two questions that arise for a central bank and that I would like to address tonight. First, how is monetary policy affected when the interbank market does not exist? Second, how can the interbank market be restarted?

The current money market environment is characterised by a high degree of mistrust among participants, based on general uncertainty and asymmetric information. I will argue that the public sector plays an important role in re-establishing confidence in the functioning of the interbank market, be it by re-shaping the market environment or by taking a temporary intermediation role. At the same time, the aim is not to permanently replace the market. The public sector needs to ensure that an exit strategy is in place that allows it to withdraw from its interfering role and to leave room for market forces to unfold in a constructive way.

2. Running monetary policy without an interbank market?

Let me start with the first question: why is the interbank market important?

A deep and liquid interbank market supports the main purpose of financial intermediation, the channelling of funds from savers to investment. In the traditional view, banks take in deposits from a large number of consumers and channel these funds to profitable investment projects. A reallocation of funds between banks may be necessary because of the rise of unexpected (or expected) liquidity needs of banks, or simply because banks are heterogeneous and specialise in different activities. Without an interbank market, such reallocation would be difficult and most likely not lead to an efficient outcome. [3]

For a central bank, a key question is how current tensions in the interbank money market influence the financing conditions faced by non-financial corporations and households. Addressing this question is central to understanding how the transmission of monetary policy to the economy as a whole has been affected by the financial turmoil. Indeed, in normal times, the money market plays a central role in the transmission of monetary policy in the euro area. Given the bank-centred structure of the euro area financial system, the marginal cost of funding bank loans (represented by interbank money market interest rates) is a key determinant of bank lending rates and thus of financing conditions. By steering very short-term money market interest rates to keep them close to its official rates, using its regular monetary policy operations, the ECB has been able to influence the longer-maturity rates that are relevant for bank loan rates.

However, in the context of the drastic reduction of turnover in the unsecured markets, especially for longer maturities, large and variable spreads have emerged between the policy rates determined by the ECB and unsecured money market rates (such as the EURIBOR at various maturities) which are the basis for bank loan rates. When no transactions are taking place, the meaningfulness of unsecured money market reference rates (such as the EURIBOR) is open to question. Yet, even if the EURIBOR is not meaningful as an indicator of money market transactions, it is still of importance from the perspective of transmission of information along the yield curve, because the interest rates applied to many outstanding loans are indexed to, or at least priced against, the EURIBOR. [4] Moreover, many derivative contracts relate to benchmark interest rates.

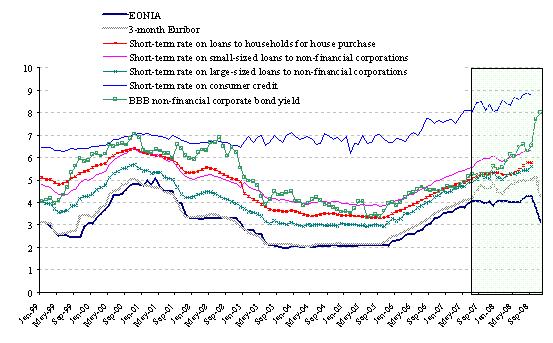

The dislocation in the usual relationship between short-term rates is illustrated by Chart 1, which shows developments in EONIA and EURIBOR rates, short-term MFI lending rates and the BBB-rated non-financial corporate bond yield since the start of EMU. Chart 1 suggests that in the most recent period during the turmoil, bank lending rates departed from their usual co-movement vis-à-vis EONIA. [5]

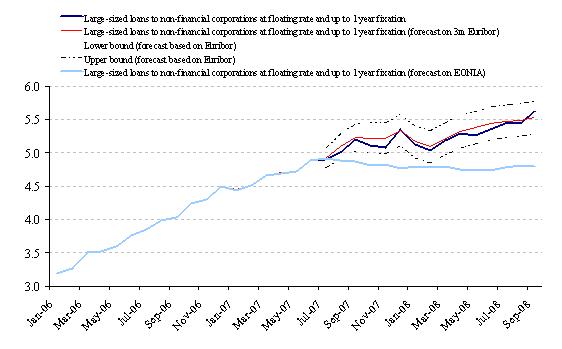

More formal empirical pass-through results suggest that despite the tensions in the unsecured money market and the resulting widening of the EURIBOR-EONIA spread up until October 2008, euro area banks so far seem to be continuing to adjust their short-term retail rates to changes in the term money market rates (see Charts 2 and 3). [6] Thus the persistence of money market tensions is hampering the smooth transmission of monetary policy.

Furthermore, it is not just the pricing of loans but also the availability of bank credit that is affected. While many euro area banks tend to depend less on wholesale funding than their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, typically having large retail deposit bases, even their ability to grant new loans depends, at least to some extent, on the possibility of using the interbank market as a marginal source of funding, especially in case of an unforeseen shock. Consequently, a complete drying-up of the interbank market has important implications for the supply of loans beyond the interest rates charged. This is all the more important as even well-managed banks become more and more dependent on obtaining funds in the overnight market, as term borrowings mature and can no longer be replaced.

Notwithstanding the importance of a functioning interbank market, central banks do have to find a way to influence the provision of credit also in its absence. In France until the mid-1980s, for example, no developed interbank market, as we know it today, existed. In this environment, the Banque de France determined the level of interest rates using bilateral relationships with a few major banks in the country, which were the only counterparties to its open market operations. Given the two-tiered structure of the French banking system, it was indeed able to steer the general level of interest rates, even though this took place in a less developed system without markets for sophisticated financial products.

In Japan, in the first half of this decade, the situation was somewhat different, as money markets were shallow not only because of the high credit risk in unsecured transactions, but also because of the extremely low level of nominal interest rates. Unable to lower interest rates further, the Bank of Japan tried to encourage the provision of credit by its policy of quantitative easing. With interest rates very close to zero, interbank trading dried up almost completely. The case of Japan illustrates well the importance of a well-functioning interbank market also for other financial products. Without a price for short-term liquidity, the market for term lending stopped functioning. Furthermore, the basis for other financial markets, such as repo, bond and certain derivatives markets, disappeared, and these markets became less liquid as well.

In the present environment, the intermediation role taken by the central bank replaces to some extent money market activity. There are limits, however, to the extent that a central bank can perform this function. First, not all participants in the money market are banks and thus eligible to interact with the central bank. This holds even for the Eurosystem, which has, compared with other central banks, a very large counterparty base. Second, the central bank cannot provide liquidity at all maturities. It can in fact only offer a standardised range of products, while the market could display much more variation. Third, the central bank treats all counterparties equally: banks obtain liquidity at uniform rates, and they can post the same collateral. In an interbank market, on the contrary, banks can vary loan rates, depending on the credit risk of the borrower. Thus, there is a role for the collection of information (or peer monitoring) here, which serves to find the appropriate valuation of liquidity. [7]

3. Creating and restarting an interbank market

Given the benefits of an interbank market, its revival is of high importance to central banks right now. The revival of a market that once existed is quite different from setting up a completely new market. In many countries, including many of the Eastern European economies, central banks supported the creation of completely new money markets. Such support is helpful if the existence of such a market is beneficial to its potential users, but especially when there are obstacles to setting it up. For instance, trading on markets may be much more beneficial once a certain critical mass of trading volume is reached; this is the concept of network externality. Also, conventions may need to be agreed upon before trading picks up in a particular market segment – in the context of the interbank market I am thinking of conventions like the establishment of certain reference rates that contracts can be based upon, such as the EURIBOR rates. Finally, only sufficient technological progress may make a market viable. For instance, short-term repo markets were in the past difficult to establish because settlement was costly and time-consuming – this was much facilitated with the advent of fully computer-based real-time settlement with straight-through processing. No individual market player can have the financial resources and the incentives to pay the fixed costs needed to set up a market, although an association of private players conceivably could.

The reactivation of a market is a different story and requires a different set of measures. The previously mentioned measures helped to overcome problems related to the infrastructure of markets, or the absence of conventions. These initiatives could help if there was a need by private agents to have such a market. Reviving a market, on the other hand, alludes to a situation in which the necessary infrastructure is in place, and in which market participants have full knowledge about products and procedures, but simply choose not to participate. The challenging task here is to encourage banks to participate again in a market, that is, to create a need to do so. More than in the setting-up of a new market, in the reactivation of the market the key hurdle to overcome is asymmetric information.

A main factor behind the drying-up of a market is the lack of trust that loaned funds will be repaid. This is based on two concerns: [8] the first is the general uncertainty about the state of the financial sector, and in particular, the future path of asset prices. The second is the currently very high degree of asymmetric information about counterparty risk. [9] As is well understood since the work of Akerlof [10], asymmetric information can lead to reduced market activity, in which only the “worst” parties are willing to trade. In the extreme, this can lead to a complete breakdown of the market: bankers, who have to decide on extending loans in an environment of extreme uncertainty, are reluctant to lend in a market in which no-one else lends. Banks with comparatively healthier balance sheets should theoretically have every incentive to lend in the market in order to signal their condition and possibly attract external financing on better terms; in equilibrium, all banks should therefore be lending to each other in order not to signal their poor quality. However, in the current environment of low confidence and trust this virtuous mechanism has difficulties to develop. The fact that transactions in the money market are over-the-counter, and therefore not widely known, could also contribute to preventing this positive signalling mechanism.

How can such market malfunctioning be avoided? In theory, there are two types of remedies to this: the first is to foster a general decrease of asymmetric information about the quality of goods that are traded in a market. For the interbank market, this would imply that better information on a bank’s credit exposure is available to potential lenders. In other words, the banking sector needs to be put on more solid grounds again. Here, one factor is to improve banks’ solvency. The second factor is to ensure that liquidity problems do not turn into solvency issues. [11] Thus, a second measure to foster interbank market activity is to ensure its liquidity. [12]

Finally, a further reason for market activity not to pick up is related to network problems. If one side of the market is basically non-existent – I am referring to the lending side of the term market – then this may reduce the incentive for participants to be the first one to act. A liquidity manager of a bank may not dare to do trades that are considered exceptional compared with others, because he may be punished more severely for any losses. Herd behaviour exists not only in booms, but also in busts, or even when markets do not exist. This has to do with benchmark remuneration practices which are very common in the financial industry. [13] The result of such practices can be multiple equilibria, some of which are characterised by a high trading activity, some by a lower one. Thus, a further action to remedy the situation could entail the steering of markets from one equilibrium to another.

4. From theory to practice: reviving the interbank market

I will now examine in more concrete terms the measures that I identified above.

The first way to limit adverse selection in the interbank market is to increase transparency. Currently, more than a year after the start of the financial turmoil, the distribution of risks among financial market players is still not entirely known. This asymmetric information is a fundamental reason for the heightened solvency concerns that led to the cutting of credit limits and the elevation of rates in the unsecured interbank market. In principle, more information about the allocation of these risks should help in re-assuring banks. As I mentioned earlier, sound banks should have an incentive to disclose detailed information in order to signal their quality. In doing so, they have to make sure that this clearly distinguishes them from more troubled banks so that a pooling equilibrium is avoided. [14] It is well conceivable that sound private banks form “clubs” in which they mutually trade.

The second measure is a reduction of credit risk in the banking sector. In the past months, in particular after the failure of Lehman Brothers, which led to an intensification of tensions in money markets, [15] European governments have discussed and put forward packages that aim at alleviating risks associated with bank assets, improving banks’ solvency and generally enhancing confidence in the banks. These include capital injections, public buying of distressed assets and issuance of government bonds that are deposited with banks. Furthermore, interbank lending guarantees (usually through new debt issuance guarantees) have been provided. These plans aim specifically at addressing the problems that hinder banks from lending to each other – that is, they can help the recapitalisation of banks that are solvent and fundamentally sound, but do not have sufficient capital, so that concerns about counterparty credit risk are alleviated. Any improvement can, of course, only be gradual, but some positive effects are already being seen in the money markets, for instance the drop of three-month EURIBOR rates that followed a wave of government rescue plan announcements.

Let me now address the third type of measure, which relates to the need to ensure that liquidity problems do not turn into solvency problems. One factor potentially triggering such a development is the classical bank run by depositors. In fear of massive runs on the banking sector, many governments, in September 2008, issued or enhanced widespread guarantees for depositors in case of a bank failure. But naturally, liquidity conditions are under the direct control of the central bank, so let me turn to the measures employed by the ECB. Since the start of the credit turmoil in August 2007, the ECB has reacted quickly and forcefully to alleviate tensions in money markets. Any measures that the ECB has taken, or might be taking in the months to come, are mainly addressed at this issue. As the monopoly supplier of central bank money, the ECB has sufficient means, valid scope and abundant flexibility to intervene. It is not, however, in a position to address banks’ credit problems. [16]

The ECB’s actions during the past one and a half years were able to stabilise the overall liquidity situation in the market, and thus avoided that individual banks’ liquidity problems could be a factor aggravating the crisis. In the first wave of measures (from August 2007 until September 2008), [17] the ECB used its general and flexible framework of monetary policy implementation to change the timing and the maturity of liquidity provision. Namely, the ECB adopted front-loading practices, where a large amount of liquidity was offered at the beginning of each reserve maintenance period and progressively reduced towards its end. It also increased the average maturity of its open market operations. Finally, it made use of swap lines with the Federal Reserve. These liquidity measures aimed to reassure banks that they would not be “squeezed” for liquidity at the end of the maintenance period, by allowing them to fulfil their reserve requirements early.

When from September 2008 market tensions dramatically intensified, a new set of temporary liquidity measures was announced by the Eurosystem on 8 October. First and foremost, all regular open market operations are now conducted as fixed rate tenders with full allotment, so that banks’ aggregate demand determines the liquidity provision to the market. Second, the width of the corridor between the two standing facilities was narrowed symmetrically to half its former size, in order to keep short-term rates under tighter control. Finally, the list of assets eligible as collateral in Eurosystem credit operations was expanded.

The aim of this second wave of measures was to assure banks that the ECB was willing to provide sufficient liquidity under all circumstances, and to eliminate fears that liquidity problems could turn into a series of bank failures. The ECB however faced a conflict between trying to achieve, on the one hand, ample liquidity conditions and smaller fluctuations of short-term interest rates, and on the other hand, to maintain an active interbank market for short maturities. Indeed, these second-wave measures were characterised by a major increase in the intermediation role of the ECB with respect to interbank money markets. Notably, the average activity in the overnight segment of the money market (which had increased after the failure of Lehman Brothers because of the replacement of longer-term lending by the rolling-over of shorter-maturity loans) declined by around 40%. Possibly, however, the activity in interbank markets would also have declined further in the absence of the ECB’s measures, as they were introduced at a time when interbank markets had all but disappeared already.

The benefits of recent ECB actions can be regarded from two perspectives. First, several of the new measures can help to re-activate the market in a direct way. The expansion of the collateral framework allows banks to post a larger variety of assets as collateral for Eurosystem operations. This should, first, increase banks’ availability of assets that can be used in the repo market, such as government securities. Moreover, it would increase the value of all eligible collateral that banks have at their disposal and promote its use in interbank transactions, given that at any time it can be used to obtain liquidity from the central bank.

Second, the narrowing of the corridor between standing facility rates, as well as the introduction of fixed rate tenders, constitute an effective protection against liquidity risk. More specifically, these measures should reassure the markets that liquidity is available at a low opportunity cost, when needed. This should provide important help to banks at the current juncture, because it effectively guarantees access to liquidity for all banks in need, thereby eliminating liquidity risk. In that sense, if a bank knows that it will always be able to get unlimited short-term funding from the central bank against adequate collateral, it might become less restrictive in extending term credit in the interbank market.

5. Further steps and open issues

Both the governmental initiatives to address credit concerns in the banking sector, as well as central banks’ liquidity provision, have helped to stabilise the situation. Three unanswered questions remain: Will these measures be sufficient to let the financial markets return to normality? What are the downsides of the proposed measures? What else can be done?

Whether the measures put forward by governments will be successful will depend crucially on their design. So far, their announcement has halted the widening of money market spreads, but they have not resulted in a significant reduction either. Some positive signs can be extracted from anecdotal evidence of at least some renewed activity in the term money market, and also in the Short Term European Paper (STEP) market, where issuance by financial institutions has slowly, but steadily, increased over the past three months. In interpreting this evidence, one should keep in mind that the market is currently preparing for the year-end, which regularly causes market tensions, and there is hope that some recovery could take place early next year.

These measures are often criticised on three grounds. First, they can be slow to implement, and, inevitably, this also affects the speed of recovery in the markets. Second, in some cases, taxpayers’ money is used to refinance an industry which has, in the past years, reaped substantial profits. [18] Third, these measures are prone to create moral hazard: that is, while they alleviate present tensions, they may be taken for granted in the future, lead to further imprudent behaviour in the banking sector, and thus sow the seeds for possible new crises. While this might be true, I believe that at the present stage, the financial crisis has reached a level where our first priority has to lie with the resolution of present problems, and there has been no alternative to acting firmly. At the same time, to limit moral hazard implications, a clear exit strategy needs to be put in place for the extraordinary interventions.

I would also like to stress that a careful design of these measures is crucial, to avoid negative side-effects as far as possible. I would like to single out some problematic aspects of government guarantees on interbank deposits. Such guarantees can indeed help in reviving the interbank market, as they eliminate credit concerns in unsecured lending transactions. However, they would entail a wide re-nationalisation of money markets and thus reverse a long process of liberalisation. Here, it is essential that the guarantees do not interfere with the Eurosystem’s ability to steer conditions in the money market. Moreover, depending on the national implementation of such measures, a substantial distortion of the various national segments of the euro area money market could result, thus impairing a common monetary policy across the euro area. For example, in its recent Opinion on the draft Austrian law on the stability of the Austrian financial market, the ECB has made it clear that “ uncoordinated decisions among Member States should be avoided as they may involve a fragmentation of the euro area money market”. [19]

Another question is whether the ECB’s measures to ensure central bank liquidity should be further amended. On the one hand, the high degree of central bank intermediation that we are currently seeing may be needed to keep banks afloat. On the other hand, the market may be ready to take a more active role, in which it relies less on central bank financing. Indeed, a situation, in which banks simply find transactions with an intermediating ECB safer, cheaper and more convenient than trading with their peers, would be an unwelcome scenario from the point of view of the ECB, among other reasons because it would make an exit more difficult. It should be stressed that our intermediation role is clearly a temporary measure which should be reversed as soon as possible. [20] In this regard, at some point the ECB may start thinking about measures that would help to reactivate the money market, such as a re-widening of the corridor in some way or other. Such a widening would reduce the intermediation role of the Eurosystem and would be a necessary measure to reactivate some segments of the money market. However, it is not a necessary condition, so one cannot be sure to which extent the money market would be revived. This would depend on other obstacles to trading – such as low credit limits – that cannot be addressed via liquidity measures.

To find the appropriate timing of further changes to the way it supplies liquidity, the ECB needs to carefully weigh the benefits of reassuring banks with regard to their liquidity concerns against the potential costs of a further, potentially massive intermediation role for the central banks, which could make the revival of the interbank market more difficult.

Three additional considerations have to be kept in mind. First, in the recent period some improvements have been noted in the financial markets, or at least it seems that the situation has not deteriorated further. EURIBOR-OIS spreads have come down and some activity has re-emerged in term markets, albeit very limited. Second, the combined effect of our measures and the government measures may take a while to be felt. Third, interbank spreads in the US and the UK are even higher than in the euro area, in spite of the lower level of interest rates. There might thus be an international dimension to the problem that can hardly be tackled with national measures only.

The above considerations suggest that work still needs to be done to induce banks to be active again in markets. However, it should be recalled that ultimately, the main factor behind the malfunctioning of the interbank market is counterparty risk, and this risk can disappear only if the commitment to avoid bank failure is credible. As I recalled in a recent speech, euro area countries have committed themselves solemnly, at the 12 October Paris meeting, to ensuring adequate capitalisation of the banks. [21] The implementation of this commitment is lagging. Furthermore, the meaning of “adequate” is subject to interpretation. Supervisory authorities continue to use their regulatory measures, and rightly so. However, markets consider that this is not sufficient and would like to see banks being further capitalised, in light of the uncertainties about the economy and about their balance sheets. Public authorities in all countries have made public money available for such recapitalisations and the ECB has defined a common pricing scheme, which would ensure a level playing-field. However, there is the problem of the “first mover”, and banks are afraid to apply for such recapitalisation because of the stigma that would be attached to it. There is thus a coordination failure that needs to be addressed by public authorities. Ideally, all banks should be provided with extra capital, in a way that is not penalising but sufficient to reassure markets that indeed no bank will be allowed to fail, even if the economy deteriorates further. This type of recapitalisation, in excess of prudential requirements, would be a way to restore confidence in the financial system and tackle the macroeconomic problems that would emerge if banks start curtailing loans to the private sector as the preferred way to achieve the capital requirements that markets request. It is important that the European authorities in charge of competition and state aid realise that such capital injections are nor aimed at addressing individual banks’ solvency but rather to promote macroeconomic and financial stability and should thus be assessed on criteria that are not only legalistic. Any time that is spent to delay these recapitalisations results in delaying the stabilisation and recovery of financial markets.

6. Conclusions

I would like to conclude by re-iterating that a fast revival of the interbank market is of high importance for central banks. Different public authorities have already taken a number of steps to increase confidence in banks and the banking sector. These types of measures may be enhanced and refined further, and will hopefully reduce credit risk, which is one of the major sources of reduced interbank market trading activity. The Eurosystem has, since the start of the turmoil, adjusted its liquidity provision to banks and ensured that banks have continued access to liquidity, to avoid situations where illiquidity might raise solvency problems. These actions have helped to stabilise the banking sector. At the same time, in an environment with remaining major concerns about credit risk in the banking sector, the ECB has increased its role as intermediary in the interbank market. When considering possible further measures to revive the money market, the ECB must carefully balance the objective of steering short-term money markets and ensuring sufficient liquidity in the banking sector, on the one hand, and its wish to foster a reactivation of the money market, on the other hand.

Finally, I would like to emphasise that both central banks and governments have done a lot to support the banking system to help it cope with the recent challenges and to restore confidence in the market. These measures, which constitute a safety net for the financial system, should act as a catalyst to recreate an environment in which financial institutions act again as financial institutions, and start again lending to each other.

Chart 1: EONIA, EURIBOR, short-term MFI rates and BBB-rated non-financial corporate bond yields(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB and ReutersNote: Last observation: end-November 2008.

Chart 2. N-step ahead forecast of the rate on large-sized loans to non-financial corporations at a floating rate and with up to one year initial rate fixation(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB and ReutersNote: Model-based forecast based on Jan. 1994-June 2007 sample. Last observation: Sep. 2008.

Chart 3. N-step ahead forecast of the rate on loans to households for house purchase at a floating rate and with up to one year initial rate fixation(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB and Reuters.Note: Model-based forecast based on Jan. 1994-June 2007 sample. Last observation: Sep. 2008.

-

[1] My thanks go to Cornelia Holthausen, Christoffer Kok Sørensen, Kleopatra Nikolaou for their input in the preparation of these remarks.

-

[2] Notably R. La Porta, F. López-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer and R. Vishny (1997), “Legal Determinants of External Finance”, Journal of Finance, 52, pp. 1131-1150, and R. La Porta, F. López-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer and R. Vishny (1998), “Law and Finance”, Journal of Political Economy, 106, pp. 1113-1155, find that countries with well-defined and adequately enforced investor rights have more liquid bond and primary equity markets.

-

[3] For a discussion of the economic functions and benefits of a well-functioning interbank market, see P. Hartmann and N. Valla (2008), “The Euro Money Markets”, in X. Freixas, P. Hartmann and C. Mayer (eds.), Handbook of European Financial Markets and Institutions, Oxford University Press.

-

[4] Many loan contracts have clauses that allow the interest rate to be de-indexed from the EURIBOR in the event of “market disruption”. However, such clauses have not been widely invoked as yet and the legal and economic implications of so doing remain uncertain.

-

[5] The only exception to this apparent change in the long-term relationship seems to be the case of short-term rates on consumer credit, which have been typically found to be rather sluggish. Also the corporate bond yield displays a more volatile pattern than bank lending rates.

-

[6] Whether short-term retail interest rates in the euro area over the past year have followed more closely the EONIA rate or EURIBOR rates can be analysed using the standard vector error-correction model of the bank interest rate pass-through where short-term retail bank lending and deposit rates are regressed against either the EONIA rate or a term money market rate.

-

[7] The importance of peer monitoring for interbank lending has been spelled out in J.-C. Rochet and J. Tirole (1996), “Interbank lending and systemic risk”, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, pp. 733-62, and M. Manove, J. Padilla and M. Pagano (2001), “Collateral Vs. Project Screening: A Model Of Lazy Banks”, RAND Journal of Economics, 32, pp. 726-44.

-

[8] See N. Cassola, M. Drehmann, P. Hartmann, M. Lo Duca and M. Scheicher (2008), “A research perspective on the propagation of the credit market turmoil”, ECB Research Bulletin, June.

-

[9] Adverse selection in the interbank market has been identified as a source of liquidity hoarding in e.g. ECB (2007), “Recent issues in the euro area money market: causes, consequences and proposed mitigating measures”, Financial Stability Review, December, pp. 89-91.

-

[10] G. Akerlof (1970), “The Market for ‘Lemons’. Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 84, pp. 488-500.

-

[11] Heider et al. study the effects of asymmetric information and counterparty credit risk on the structure of the interbank market and analyse the effects of different policy responses; see F. Heider, M. Hoerova and C. Holthausen (2008), “Information asymmetries in the interbank market: theory and policy responses”, presented at the 2008 UniCredit Conference on Banking and Finance, Vienna, 6-7 November.

-

[12] A decomposition of the spread in the unsecured market into a liquidity and a credit risk component is done in ECB (2008), Financial Stability Review, June, Box 10, pp. 82-84.

-

[13] See J. Zwiebel (1995), “Corporate Conservatism and Relative Compensation”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 103, pp. 1-25, and H. Hong, J. Kubik and A. Solomon (2000), “Security analysts’ career concerns and herding of earnings forecasts”, RAND Journal of Economics, 31(1), pp. 121-44.

-

[14] A. M. Spence (1973), “Job Market Signaling”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 87, No. 3, pp. 355-374.

-

[15] Heider et al. (2008) map different phases of recent money market tensions into equilibria that are characterised by varying degrees of adverse selection.

-

[16] J. Taylor (2008), “A black swan in the money market”, NBER Working Paper 13943, points out that indeed the actions of the Federal Reserve did not help to alleviate tensions related to credit concerns.

-

[17] For details, see ECB (2008), “The Eurosystem’s open market operations during the recent period of financial market volatility”, ECB Monthly Bulletin, May.

-

[18] For some measures, such as guarantees, the actual credit exposure of the Treasury might be limited, as the sheer announcement, not its actual use, could prove to be effective.

-

[19] See the Opinion of the European Central Bank of 20 October 2008 at the request of the Austrian Ministry of Finance (CON/2008/55).

-

[20] However, according to W. Buiter (2008), “Central banks and financial crises”, paper presented at the annual Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s symposium at Jackson Hole, the temporary replacement of short-term market segments by central bank intermediation is not in itself harmful.

-

[21] “Restoring Confidence”, Madrid, 25 November 2008 (www.ecb.int).

Banco Central Europeu

Direção-Geral de Comunicação

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A reprodução é permitida, desde que a fonte esteja identificada.

Contactos de imprensa