From Tuscany’s 19th century currency, the fiorino, to the euro: dialogue on international finance

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBin the Sala Luca Giordano at the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence15 May 2008

I’m very pleased to come back to Florence to consider a highly topical subject linked to the effects of the financial turmoil on the world economy.

To understand the current economic situation and the current short to medium-term prospects we need to take a step back and consider the imbalances that were building up on our continent until mid-2007, imbalances that were evidently unsustainable and that underlie the corrections we are going through.

We have to distinguish three main imbalances.

In chronological order, the first one concerns international payments. Over the years, the United States has accumulated huge deficits on its current account which have grown out of a lack of domestic savings. The US economy was essentially growing by borrowing from the rest of the world. In 2007 the US current account deficit amounted to over 6% of its GDP.

For years the problem of the sustainability of America’s external imbalance has been emphasised, especially in Europe, which feared the risk of a disorderly unwinding with destabilising effects on the financial markets. The typical response from the other side of the Atlantic to such fears was that in a globalised world these imbalances are physiological and do not cause problems so long as they are financed with capital inflows. Moreover, the status of the dollar as sole international reserve currency used to guarantee such financing. In the end, the theory (which in fact is no more than an accounting identity) was put forward according to which America’s deficit was in reality the other side of the coin of an excess of savings in the developing countries, resulting inter alia from the fixed exchange rate policy vis-à-vis the dollar. The adjustment had therefore to start first of all from a modification of the policy of the other countries, rather than from the recovery of the savings capacity of American households. In synthesis, the prevailing theory up to recently was that the US imbalance was physiological and its correction, if any, would have implied no painful adjustment on the US economy.

The second imbalance that has built up in recent years relates to the development of financial products that have loosened the ties between lenders and borrowers. Securitisation, which has enabled lenders to spread risk better, restructuring it and selling it to others, has however reduced the incentive to value it correctly, either by those who originated the product or those who acquired it. The sub-prime mortgages in the United States are an example of how certain risks can be underestimated if they are sold on to others, perhaps with opaque contracts. The loss of trust in certain kinds of financial contract, in particular in relation to their liquidity, has reduced the incentive to finance such operations, giving rise to chain reactions in all the markets.

In this case too, the alarm was raised some time ago. I recall, for instance, a Financial Times article at the end of January 2007, six months before the start of the turbulence, which quoted a comment made by the President of the ECB at Davos, namely that international markets were underestimating risks and had to prepare for a substantial adjustment in the prices of financial assets.

The response of the market operators to these warnings, in particular from the other side of the Atlantic, was: “We’ll keep dancing until the music stops”. One should not interfere with the market mechanism or lean against asset prices. Financial innovation, also in mortgage markets, was a positive development as it allowed households, also the less well-off, to finance consumption and investment.

Not everybody shared this position. As early as February 2005, Paul Volcker, former Chairman of the Federal Reserve had drawn attention to the imbalances in the US economy, ranging from the balance of payments deficit and the possible bubble in house prices to the excessive household indebtedness. In his view, a correction of these imbalances was inevitable.

The third imbalance is the one that results from globalisation and from the escape from poverty of hundreds of millions of people, notably in China, India and elsewhere in Asia as well as in Africa, a change which is putting pressure on energy and agricultural commodity prices. The imbalance between growth in global demand and rigidity of supply points to scarcities that are reflected in prices. The uncertainties of the financial markets have in the end contributed to price tensions.

Also in this instance, the alarm was raised some time ago, although little notice was taken. The price of oil, for example, was around USD 20 a barrel in 1999 and in the eight years thereafter it rose fivefold (tripled when priced in euro). Fortunately, European countries have resisted the temptation to reduce energy taxes, which would have led to an increase in demand and therefore ultimately raise the rich countries’ oil bill. On the other hand, other industrial countries have continued to keep energy taxation at very low levels, in order to support consumption. In some cases production of “bio-fuels” has been encouraged, which has led to further distortions in energy and food prices. The main oil and energy companies until two years ago have continued to price oil at USD 40 a barrel in their industrial plans, thus underestimating the need – and the opportunity – for investment in order to increase supply.

The combination of these three imbalances is the source of the economic slowdown under way, above all in the United States, accompanied by strong inflationary pressures and by financial turbulence unfolding since the last summer.

Overcoming the current economic phase implies some correction of the imbalances I have just mentioned.

Two questions come to mind:

How long will the current critical economic and financial phase last?

What can economic policy do to speed up the correction and alleviate its costs?

The reply to the first question is that probably more time will be needed than is thought to overcome the current adjustment because the imbalances that underlie this critical period go back a long way and will take time to unwind.

Time will be needed, in particular, before American households start saving again in a significant way, to run down part of their debt. In the short term, this may involve slower growth for some years.

Time will be needed before the financial operators regain trust in the capacity to resort to sound sources of finance so as to be able to reduce their current high appetite for liquidity. Some financial instruments will remain relatively illiquid, until the prospect of a capital gain will not become realistic gain. It will not however be possible to return to the very low levels of risk remuneration seen in recent years. Credit institutions will have to rethink their business models in order to better assess the opportunities for growth based on the availability of capital.

Time will also be needed before the supply of commodities can react to demand in such a way as to keep prices down. As for agricultural commodities, the use of new productive land implies long-term investments and implementation times. Climate change could increase the variability of supply. The same applies to energy commodities. Without a stronger policy of energy saving, in particular in the US, the equilibrium between demand and supply cannot be ensured at moderate price levels.

In brief, there are, above all, structural factors at the heart of the current crisis which will take time to recover. This suggests that to accelerate the adjustment economic policies of a structural rather than cyclical nature are necessary.

Let's turn to those economic policies. What are the do’s and don’ts in the light of both economic analysis and of past experience?

Let’s start with the don’ts. What do the errors of the past teach us and, in particular, what was done in earlier crises, in 1929, 1974-75, 1992-93 and in 2001-2002?

There are at least four errors that should not be repeated.

The first error that should be avoided is to allow that some exogenous price increases lead to a generalised higher inflation on a permanent basis. The rise in headline inflation must remain temporary and limited to food and energy prices, and not spill over other sectors of the economy. From this standpoint, the gravest danger is to index wages to inflation and, in particular, to inflation of external origin. This is a well-known finding in the economic literature and broadly confirmed by experience. The countries with wage indexation mechanisms are those that have least capacity to cope with external shocks like the oil price increase. They tend to feed into a wage-price spiral, with negative effects on purchasing power and employment. This experience is not unique to the 1970s. Even today in the euro area, countries like Spain that still have indexing mechanisms have above-average inflation. Unemployment has started to rise again – the first sign of an economic slowdown; the unemployment rate in Spain is at around 9%, compared with 8% in the middle of last year. In Italy, where there is no automatic indexing, the unemployment rate is below 6%, the lowest level since the early 1980s.

It would be especially damaging for employment and inflation if the reform of the Italian wage bargaining system currently under debate, aimed at tying wage levels more strongly to productivity, were to contain inflation indexation clauses. Even worse would be the situation if a possible indexation were to be tied, as some are advocating, to a price index of frequently purchased goods, such as that developed by ISTAT for analytical purposes and reflecting only the frequency of purchases, not their economic value.

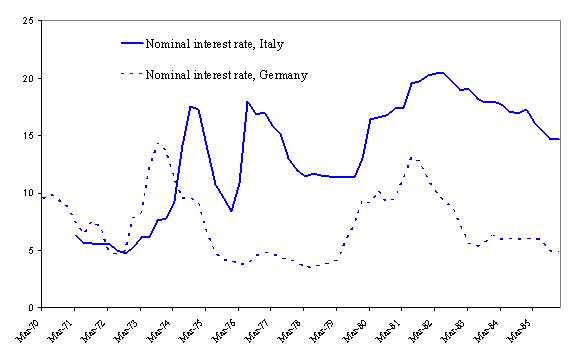

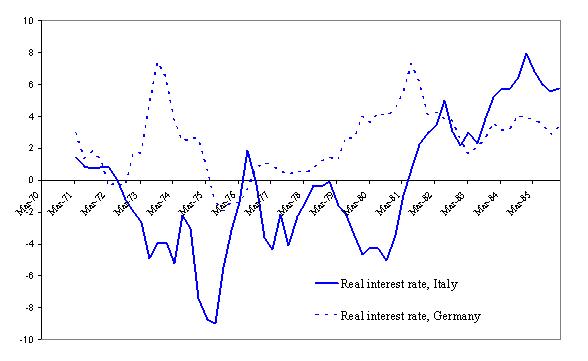

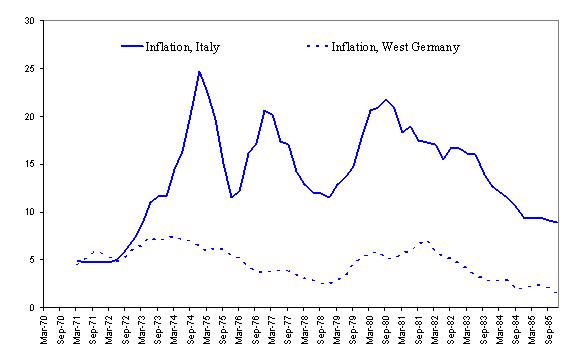

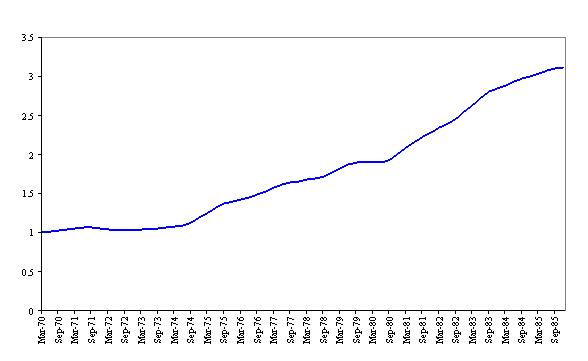

The second error to avoid is to tackle the effects deriving from a supply shock, like that connected to the increase in the oil price, with policies to stimulate demand. If the increase in oil price and other commodities is protracted, anticyclical policies simply postpone the adjustment by several months, making it more expensive. From the first oil shock – in the mid-1970s – it is possible to gain very clear insights that ought not to be forgotten. The comparison between the experience of Germany, which avoided using monetary and fiscal policy to compensate for the loss in purchasing power caused by the increase in oil price, and that of Italy, which instead sought to stimulate domestic demand is illuminating. The German economy and that of other countries which followed the same path emerged stronger from that difficult phase of adjustment than countries like Italy which followed the illusions of Keynesianism and only engineered a higher inflation rate. [1] The depreciation of the exchange rate did not allow to increase market share on a sustainable basis. Italy is still paying for that error, with a public debt above 100% of GDP and a debt burden that weighs heavily on taxpayers.

The third error that history invites us not to repeat is to put up protectionist barriers to stop or impede the economic and financial integration under way at global level. Experience shows that such measures damage economic growth and tend to worsen crises. The 1929 crisis was characterised not only by its deepness but also by the policy mistakes committed at the time, which introduced protectionist barriers with the aim of protecting national economies from international competition in the hope that this would succeed in better coping with the crisis. Many countries adopted measures to restrict trade with the aim of favouring local production at the cost of imports and trying to protect jobs. In June 1930 the United States introduced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which imposed disproportionately high duties on imported goods. Other countries took retaliatory measures. International trade declined (some say it contracted sharply), deepening the depression and delaying the recovery. [2]

At the current juncture one the few factors supporting growth is international trade, driven in particular by emerging economies. Without this contribution, growth would be stalling completely in advanced economies. Under these conditions, thinking of curbing international trade would be a mistake in the same way as in 1929.

To isolate a country from globalisation means weakening it economically. The empirical evidence shows that there is a clear relationship between a country’s degree of integration in the global economy and its economic performance over a relatively long period of time. It is the more integrated countries that compete better and develop, not those which shut themselves off from competition.

The microeconomic evidence confirms the macroeconomic trends. Firms, including Italian ones, which have restructured and are exposed to international competition have become more productive, have started to regain market share, have improved their productivity and started to pay their employees higher wages. By contrast, firms which are protected from competition and benefit from having a monopoly or from national or local restrictions on trade, and perhaps even benefit from state aid tend to pass their higher costs onto consumers. I don’t need to tell you that there are some Italian firms which are flourishing without state aid, while others don’t have real growth opportunities and continue to be a burden on taxpayers because they receive support from the public sector.

Finally, protection from international competition means higher prices, as quotas and tariffs are a form of taxation. This weakens consumers’ purchasing power, and particular affects the poor. There is really no need to favour price increases in these times of higher inflationary pressures.

The fourth mistake that needs to be avoided is to intervene in financial markets without considering the perverse incentives that may result from these actions. Whatever measure aimed at supporting financial institutions in distress due to market turbulence should not allow those who have made mistakes to avoid paying the price for them. Should this happen, they would be tempted to do the same thing again.

The measures taken in recent months by central banks, including the ECB, aimed at supporting market liquidity but, at the same time, not to relieve investors from solvency risks, go in this direction. Even the rescue operations undertaken in the US in order to protect systemic stability have been accompanied by some form of penalty for the managers as well as the shareholders who had not paid enough attention to their behaviour.

It is also important to minimise regulatory changes that could induce investors to cover up their losses, especially during an adjustment of market prices, as this could weigh on transparency and market confidence. It is surely desirable to support long-term as opposed to speculative investment, and protect long-term investment from the perverse effects of market volatility, but this should be accompanied by supervisory measures that would certify that the investment in question is really a long-term one and is not subject to liquidity risks.

Let me now turn to the things that should be done. Also in this case I would like to highlight four of them. Three of them involve actions at European level, as either the competence has been transferred to that level or the international partners are of such large size that it would be futile for individual European countries to address them separately.

A first important step has already been taken: it is the euro. I will not dwell on the benefits that citizens and firms gain from having a stable currency like the euro in such a financial crisis, even though they do not often realise them. It is important not to forget it.

Let me just recall how the US recession in the early 1990s affected Europe in 1992-93, leading – in the presence of uncoordinated economic policies within Europe – to serious economic and financial turbulence. The ERM crisis and the exit of the Italian lira and the British pound in the autumn of 1992 as well as the widening of the fluctuation bands of the ERM led to large changes in competitiveness, with an overall contractional impact even on the stronger economies such as Germany.

It is difficult to imagine what would have happened in recent months without the euro. If the past is a good guide to understand the future, we can be sure that Italian inflation and interest rates would be higher, with negative repercussions on consumption and investment. We can only guess what our oil bill would now be if we had a weak currency instead of the euro. Likewise, just imagine the situation for households having mortgage debt who would have to pay substantially higher interest rates.

Monetary stability requires a monetary policy focused on medium-term price stability. Especially in a phase of higher uncertainty such as the one we are currently experiencing there must be no doubt about the priorities of the central bank, or about its strategy and independence. There can certainly be no doubt about the attitude of the European Central Bank. Those who had doubts in the past must have now changed their minds.

The second line of action concerns financial markets. On this matter there is now a precise action plan, agreed at international level within the framework of the Financial Stability Forum. Within 100 days a number of regulatory, and self-regulatory, measures need to be approved, aimed at improving transparency and risk management. Among these measures some are particularly relevant: the introduction of standards for disclosing the exposure to off-balance sheet items; asset valuation methods where the underlying asset is illiquid; more generally, a higher degree of transparency for banks’ exposure to structured financial products. Rating agencies are called upon to improve their evaluation and to reduce possible conflicts of interest. As far as regulators are concerned, more international cooperation is required, for example through the creation of a “college of supervisors” for large and global financial groups.

The third priority is to tackle the problems related to global imbalances, together with other main players of globalisation in the relevant bilateral and multilateral fora. Globalisation cannot be stopped. Governments must act, within the framework of existing rules. In this regard, Europe has a major responsibility.

Concerning international trade, Europe can only gain from the completion of the Doha round, so that WTO rules are respected, particularly regarding intellectual property rights. The recent price increases of agricultural products should make it easier for the EU to make some concessions on the Common Agricultural Policy, in order to eliminate the subsidies which tend to distort international prices. This would be an advantage for European producers and consumers alike.

Regarding currencies, it is important to continue talking with those countries which still peg their currencies to the US dollar, although their economies show a higher growth rate and a strongly positive balance of payments. Pegging to the US dollar slows down the adjustment of global imbalances. A speeding-up of the appreciation of the exchange rate of the yuan vis-à-vis the US dollar as well as the euro would be in the interest not only of the international community, but of China itself. In the past 12 months, the exchange rate of the Chinese currency has gained approximately 9% vis-à-vis the US dollar, while losing about 3% vis-à-vis the euro. Only in the past months have markets experienced the inverse process, with the yuan gaining also against the euro.

The appreciation of the yuan would allow China to effectively counteract internal inflationary pressures and to reduce the balance of payments surplus, which fuels the accumulation of global imbalances. The increase in food prices should ease fears that an appreciation of the yuan could penalise the income of rural areas, which are still quite sizeable.

The euro area has to act together, exerting some pressure on the IMF, which last year adopted a resolution to effectively strengthen its surveillance of currency markets.

Lastly, regarding energy issues, it is necessary that developed countries, including Europe, put a stronger emphasis on energy savings and climate change. The experience accumulated in recent years has confirmed that although energy saving measures can slow down growth in the short term, costs connected to energy waste can be much greater in the long run.

I will now close with the fourth line of action, which is linked to the previous one, though being on a more national scale. The ability of a European country to become part of the globalisation process depends not only on EU-wide initiatives but also on internal measures aimed at supporting economic growth. In essence, there are only two ways of absorbing the shock deriving from price increases in raw materials and to prevent it from becoming a reduction in purchasing power. The first way is to increase productivity in order to allow wages to grow in a non-inflationary manner. The second is the reduction in the price of items other than energy and food. Of course, these are not easy ways, but they are the only ones which can allow European economies to grow while preserving the purchasing power of its citizens, even in the presence of a worsening in the terms of trade.

The measures which should be taken are well known: they are in the field of competition, the liberalisation of markets, services and labour and above all the development of human capital, which constitutes the first basis of productivity and hence income. This is the path taken by those European countries which have experienced higher growth than others in the past months and years, while at the same time sharing the same currency, the euro.

The data released today on real GDP growth in the first quarter of this year confirm that those countries which have followed the path of improvement, structural reform and cost discipline have shown a greater resilience and have managed to achieve growth even when faced with a negative external shock.

This is the way to go if we want to move away from the current stalemate.

Figure 1. Nominal short-term interest rate, Italy and West Germany, 1970-1986

Source: OECD.

Figure 2. Real short-term interest rate, Italy and West Germany, 1970-1986

Source: OECD.

Figure 3. Inflation rates in Italy and West Germany, 1970-1986

Source: OECD.

Figure 4. Competitiveness as measured by the relative unit labour cost, Italy vs. Germany (1970=1)

Source: European Commission.

-

[1] See Figures 1-4 in the Annex.

-

[2] See, for example, D. Irwin (1998): “The Smoot-Hawley Tariff: A Quantitative Assessment”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 2, pp. 326-334.

Banque centrale européenne

Direction générale Communication

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Allemagne

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction autorisée en citant la source

Contacts médias