Creating stability in an uncertain world

Speech by Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB,at the conference "Brexit and the implications for financial services" jointly organised by SUERF and hosted by Ernst & Young,London, 23 February 2017

Resilient recovery in the euro area

The economic recovery in the euro area is continuing at a moderate, but firming, pace, and is broadening gradually across sectors and countries. Real GDP growth has expanded for 15 consecutive quarters, growing by 0.4% during the final quarter of 2016 according to the Eurostat flash estimate. Economic sentiment is at its highest level in nearly six years and unemployment is back to single-digit figures. Looking beyond the euro area, the global economy, too, is showing increasing signs of a cyclical upturn.

The euro area economy has been resilient in the face of a number of risks and uncertainties at global level. One example of its improving resilience is the fact that domestic demand is now the mainstay of real GDP growth. Previously, growth in euro area was closely correlated with the strength of international trade, but that relationship has weakened recently; last year’s growth would not have been possible in view of the lacklustre international conditions.

Our monetary policy measures have been a key contributor to these positive economic developments. The comprehensive set of measures introduced since June 2014 has worked its way through the financial system, leading to a significant easing of financing conditions for consumers and firms. Together with improving financial and non-financial sector balance sheets, this has strengthened credit dynamics and supported domestic demand.

The recovery has been accompanied by a broad-based improvement in measures of confidence. Measured confidence for industry, construction, services and households is in positive territory, and particularly strong for measures of future expectations. This is in line with the normally high correlation between measures of confidence and economic activity. Households and businesses which are confident about the future are more likely to spend and invest than those which are concerned.

Despite the resilient recovery in the euro area, and strong indicators of confidence across all sectors, measures of political and policy uncertainty have been rising recently, although asset markets are not significantly pricing in tail risks. The recent bouts of uncertainty are a source of concern, and represent a downside risk to the economic outlook. Today I would like to discuss the potential impact of uncertainty on economic activity and the role of institutions in counteracting uncertainty and providing stability.

Uncertainty and economic developments

The economic literature – both theoretical and empirical – finds a link between heightened uncertainty and lower economic activity in the short run. There are usually fixed costs involved with investment, from creating new capital such as building a factory to hiring new staff, which cannot be recovered if the investment decision is reversed. So faced with an increase in uncertainty, businesses pare back investment plans. Similarly, if households fear unemployment or lower income from employment in the future they may reduce consumption today.[1]

The literature uses a number of different measures of uncertainty. Such measures usually move with each other, and generally peak in recessions. At the current time, most measures of uncertainty for the euro area do not appear especially elevated. The economic recovery has been resilient and steady for a number of years, the financial sector is more robust than it was pre-crisis, and most measures of financial sector volatility are markedly below the peaks witnessed during the crisis.

Chart 1: Measures of euro-area uncertainty

Sources: ECB (for SSCI), Baker, Bloom and Davis (for EPU), BIS and ECB (for financial market uncertainty), European Commission, Eurostat and Haver (for macro conditional variance) and ECB calculations. CEPR for recession periods.

The one indicator of uncertainty that appears elevated, and has been so since the UK referendum is political uncertainty.[2] This measure counts how frequently newspaper articles cite “uncertainty”, “economy” or similar, and particular policy words, such as “deficit” or “regulation”. A number of recent events have sparked this rise in political uncertainty. Since the US elections, the outlook for that country’s fiscal policy and trade policy has been uncertain. In the run-up to the elections in several European countries, the headlines are reflecting political uncertainty about the future attitude of Member States towards European integration. Not to forget the process of withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union and the significant uncertainty that inevitably surrounds the future relationship between the UK and the EU27.

These recent bouts of political and policy uncertainty have come on top of the existing and more enduring sources of “structural” uncertainty about the economic outlook in advanced economies. What do we really know about the impact of new technologies and innovation on tomorrow’s economic landscape? Will secular stagnation be the new economic reality? Various authors have suggested that recent innovations have had only limited effect on productivity and growth in advanced economies. Others have expressed concern that these innovations may polarise societies still further and may even have negative effects on employment. Technology optimists meanwhile predict the advent of a bright future, with the diffusion of innovation bringing about significant productivity increases and high levels of well-being.

It is important for us economists to be humble when forecasting the future. Debating concepts such as ‘secular stagnation’ may be fashionable now, but we should remember only a decade ago it was fashionable to debate the ‘Great Moderation’. By the same token, the observed resilience of a moderate economic recovery and strong confidence indicators should not lead to complacency. Respondents to survey questions can be influenced by what they consider to be a normal benchmark. If the new normal after the Great Recession is below its pre-crisis level, the same levels of confidence indicators can point to lower growth rates than before the crisis.[3] Indeed, measures of capacity utilisation are high in an environment of persistent economic slack. How resilient the recovery really is to policy uncertainty is also not known. The World Bank’s Global Trade Watch[4] report suggests that policy uncertainty is already weighing on world trade.

Of course, uncertainty about the future has always been with us. The incidence of natural disasters such as droughts, floods and earthquakes, the doubt of whether contractual promises will be honoured and the fear of your possessions being taken by force are all factors that can affect economic activity.

Humankind, over the millennia, has put in place various mechanisms to help cope with uncertainty. For example, putting in place narratives to filter and process the vast array of information available and arrange it in order – a cognitive trick to make sense of an uncertain world. Building institutions has been key to providing economic stability. Inclusive institutions are essential for economic development.[5]

The importance of economic narratives

Following financial crises, political uncertainty is often elevated. According to a recent study,[6] votes for extreme parties can increase by on average 30%, while government majorities shrink, parliaments end up with a larger number of parties and become more fractionalised. Thus the political landscape becomes more gridlocked at precisely the moment when decisiveness is typically required.

This can delay necessary policy responses, such as cleaning up the financial sector, which prolongs the post-crisis recovery. And such uncertainty, reflected in the media, can gradually build a narrative of doom and gloom around the economy or around the existing institutions – a seeping pessimism, which over time alters investors’ and consumers’ expectations, and thereby their behaviour.

Robert Schiller[7] has recently elaborated on the epidemiology of narratives relevant to economic fluctuations, ranging from the Great Depression of the 1930s, to the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and today’s climate of political uncertainty. Popular narratives can drive economic developments. For example, when people hear stories of declining prices and then postpone their purchases: talking about deflation feeds deflation. But the relationship is more than just one way: actual events play some role in the development of popular narratives. Overall, popular narratives act as potent multiplier of economic shocks – the “animal spirits” of Keynes.

Today’s information and communication technologies have opened up a vast field of research into the role of narratives as determinants of economic developments. These technologies have also greatly accelerated the diffusion of narratives in our societies; it is surprising how easily fake news can flourish nowadays.

This is a serious matter. The outcome of the UK referendum can be partly attributed to the decades-long development and spread of negative popular narratives about European integration. More generally, the events I mentioned earlier are the culmination of a broader anti-establishment and anti-globalisation narrative that has gained more traction in advanced economies. As narratives often are key determinants of economic and political outcomes, it is important to be wary of them.

The stabilising role of institutions

Institutions contribute to stability, especially in times of uncertainty, and help anchor expectations. In times of political gridlock, effective institutions are vital since they can deliver their mandates decisively and outside of the push-and-pull of the political process. This in turn foreshortens the crisis and the self-fulfilling cycle of weak economic performance and gloom-and-doom narratives.

For example, while bank failures are always possible, the existence of appropriate institutions can mitigate their impact. A sound supervisory framework, for instance, makes failures less likely, while resolution plans contribute to seamless unwinding of failed institutions. This is also true of shocks exogenous to the economy. In the case of natural disasters such as earthquakes,[8] building standards – properly enforced – can reduce deaths, and disaster recovery plans can help after the event.

The move over recent decades to grant independence to central banks owes much to the problem of time consistency. When monetary policy was under the control of governments, there was always an incentive to “cheat” and deliver higher than expected inflation to temporarily increase output. The existence of this incentive, and the inability of governments to credibly commit to the right policy, gave rise to de-anchored inflation expectations.

Independent central banks with a clear mandate to maintain price stability have been successful in anchoring inflation expectations. Having an explicit inflation objective provides its own stabilising narrative – people can trust the central bank to deliver inflation, and can base their economic decisions on that expected inflation rate. In recent years, the ECB has been an anchor of stability, creating an effective bulwark against deflationary narratives when they appeared in the euro area. By acting forcefully, the ECB has prevented deflationary dynamics from materialising.

But institutions need to be strong in order to deliver in the face of shocks. To put this in perspective, consider how two periods of global economic integration have fared under different institutions. Global economic integration has fluctuated over time and is now higher than at any time in the past. Another period of high integration, in the decades prior to World War I, ended abruptly as a financial crisis of global proportions, accompanied by a credit crunch, broke apart bilateral arrangements and paved the way for several rounds of retaliatory tariff increases.

Multilateralism has been a cornerstone of economic expansion since World War II. The current legal framework for world trade, embodied in the multilateral World Trade Organization, has proven much more robust to the recent global financial crisis. It has played a key role in preventing the re-emergence of protectionism in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

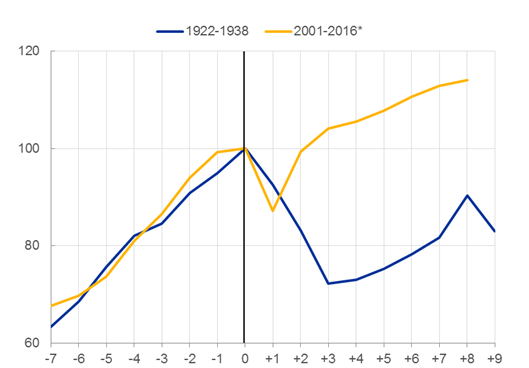

Three stylised facts emerge from comparing the evolution of world trade in goods in the periods 1922-38 and 2001-16. First, the pre-crisis expansion was very similar in both eras. Second, world trade collapsed in 1930 and 2009, immediately after the two shocks, but the decline was sharper in 2009, even though the total decline in the 1930s was larger. Third, the subsequent recovery has been noticeably stronger in the most recent episode.

Chart 2. The evolution of world trade in goods during the Great Depression and the Great Recession

(volumes; 1929 and 2008=100, respectively)

Sources: ECB staff calculations based on data in Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016)[9] and CPB Trade Monitor data.

Notes: The year 0 on the horizontal axis is 1929 in the case of the Great Depression (blue line) and 2008 in the case of the Great Recession (yellow line). 1922-1938 trade flows are constructed using current country borders. Data for 2016 are available until November.

On both occasions, falling output was the main driver of the trade collapse, but protectionism after the Great Depression was largely due to the emergence of a new political constituency opposed to free trade which, in many cases, was able to develop convincing narratives for the continuation of protectionism even when the crisis was over.

Institutions provide stability by their very nature of being hard to change. But that inertia can lead them to lack the agility to deal with new challenges. Failure to react can fertilise counter-narratives. But there is also a chance for new institutions to be founded which improve on previous institutions. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created in the United States in 1933 to reduce the effect of failed banks on depositors. Following the recent financial crisis, the international institutional architecture was strengthened with the inauguration of the G20 summits and the creation of the Financial Stability Board. In the euro area, the establishment of the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism has strengthened the financial system and made it more resilient to future shocks.

While the current multilateral framework has so far protected against rising protectionist sentiment, it is worth recognising that anti-globalisation and anti-establishment sentiments have not disappeared. There is an increasingly common belief that the benefits of globalisation have not been distributed widely enough and that it has reduced protection for workers. Let me take a few moments, then, to remind you of the successes of the post-war institutions in Europe.

The European Union as provider of stability and protection

The European Union and the Single Market have successfully delivered decades of peace and growing prosperity throughout Europe. There has been a steady process of strengthening trade and economic links, based on the foundations of democracy, a strong social model and the rule of law. These institutions are Europe’s answer to the questions posed by globalisation, a democratic way to reap the benefits of economic integration while still protecting consumers and workers.

The Single Market is more than just a customs union or a dense network of free trade agreements between countries. It is in fact an innovative forward step in economic evolution. It provides the legal framework for trade between Member States, underpinned by the four fundamental freedoms – free movement of goods, services, labour and capital.

This framework is vital to give companies confidence to invest and integrate across national borders. For trade to flourish, businesses need to be certain that contracts will be honoured, competition rules will be fairly enforced, property rights respected and standards adhered to. In ensuring the rule of law, the Single Market reduces barriers to trade, labour mobility and competition and increases technological diffusion between countries. Take as a recent example the abolition of mobile phone roaming fees across the Union, which was a decision based on the principles of the Single Market that protects consumers.

This is not to say that the European Union is perfect. Strong institutions should always strive to improve and make sure their policies bring more value to citizens. We should also be clear about what European institutions are and what they are not. There is a widespread narrative according to which Brussels imposes its decisions on Member States. Yet all regulations and directives adopted in Brussels are decided according to a political process involving the governments of all Member States, which are all represented in the Council, and elected representatives of all European citizens. The Union has built over time a set of strong institutions for Member States to decide together matters of common interest.

But it is important to recognise the tensions that exist between the individual priorities of nation states and the pooling of national sovereignty for mutual gain. The regulations for the Single Market need to be strong enough to promote innovation, but not so tight that they stifle it. By the same token, countries have to be able to pursue their own social agendas where these do not clearly clash with the principles of the Single Market. The principle of subsidiarity is important.

Take as an example the fiscal framework under the Stability and Growth Pact. There are important rules to ensure government finances are run in a sustainable fashion. Yet beyond the parameters for fiscal sustainability, the framework allows for wide divergences in aggregate tax rates, the share of the public sector in total output and for national priorities in public spending. These are at the discretion of each sovereign Member State.

Conclusion

Let me return then to my original observation of the apparent disconnect between elevated measures of political uncertainty on the one hand, and other measures of uncertainty at more benign levels and robust measures of confidence on the other hand.

One of the reasons why prevailing political uncertainties do not weigh on confidence is perhaps the existence of strong institutions at both national and international level. Markets continue to believe in the strength of the rules-based international order and its institutions. It has been a steady process of strengthening economic integration, and households and businesses demonstrate by their current decisions on consumption and investment that they believe that there will be no sudden reversal of this process.

This should however not lead to complacency. An alternative explanation is that adherents of the anti-establishment narrative truly believe that the future will be brighter once current institutions are swept away and are acting coherently with that world view. History has proven that accidents are possible, that protectionism can succeed periods of free trade. We should all be wary of the filters that our own narratives put on our ability to process information. Brexit proves that there is a possibility for European integration to go into reverse. A more widespread reversal of European economic integration would durably jeopardise economic prosperity.

Let me end on one final comment. The success of our monetary policy measures throughout the crisis has laid the ground for a new narrative, that of the ECB being the “only game in town”. We have proven able and willing to take the measures necessary to support a sustained adjustment of the path of inflation back to our objective. This new narrative deserves a word of caution: there is only so much monetary policy can do. Monetary policy alone cannot ensure all macroeconomic goals are met. It cannot by itself bring about any redistributive measures required to bring the benefits of globalisation to all. A greater contribution is required from other policies. Structural reforms are also required to build resilience to country-specific shocks and ensure the full diffusion of innovation across the Single Market to maximise the benefits to all citizens. Carrying out these reforms will continue the decades-long progress of European economic integration and ensure that the benefits of stability and protection will be maintained in the future.

[1]For a more detailed discussion of the economic impact of uncertainty, see “The impact of uncertainty on activity in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2016, ECB and “Uncertainty about Uncertainty”, speech by Kristin Forbes, External MPC member, Bank of England, 23 November 2016.

[2]This measure is derived from a method proposed by Baker, S., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. (2015), “Measuring economic policy uncertainty”, NBER Working Paper Series No 21633.

[3]European Commission, European Economic Forecast, Winter 2017. Box 1.2 “A ‘new modesty’? Level shifts in survey data and the decreasing trend of ‘normal’ growth”.

[4]Trade Developments in 2016: Policy Uncertainty Weighs on World Trade by Constantinescu, C., Matto, A., and Ruta, M. (2017)

[5]On the importance of inclusive institutions, see Acemoglu D. and J. Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty.

[6]Funke, M., Schularick, M., and Trebesch, C. (2016), “Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870-2014,” European Economic Review, 88(C): 227-260.

[7]Robert Schiller (2017) Narrative Economics, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 23075

[8]Noy, Ilan, (2009), "The macroeconomic consequences of disasters," Journal of Development Economics, vol. 88(2): 221-231.

[9]Federico, G. and Tena-Junguito, A. (2016), “A new series of world trade, 1800-1938”, EHES Working Paper, No. 93.

Banque centrale européenne

Direction générale Communication

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Allemagne

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction autorisée en citant la source

Contacts médias