Assessing the new phase of unconventional monetary policy at the ECB

Panel remarks prepared by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB, at the Annual Congress of the European Economic Association, University of Mannheim, 25 August 2015

It is a great pleasure to participate in this policy panel and to share the stage with such distinguished fellow participants.

My plan today is to present some key features of the monetary policy measures recently implemented by the ECB. As you all know, in January this year the ECB launched the most recent addition to its suite of tools – the public sector purchase programme (PSPP), popularly referred to as quantitative easing. Together with a programme of targeted liquidity provision and a programme of private sector asset purchases, the PSPP marked a new phase of the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy. Previous non-standard measures were mainly aimed at redressing impairments in the monetary policy transmission mechanism and fostering a regular pass-through of the monetary policy stance. Their implications for the ECB’s balance sheet were accommodated in a merely passive way to satisfy the liquidity demand created by banks. In contrast, with the new measures implemented since June 2014, the Governing Council is more actively steering the size of the ECB’s balance sheet towards much higher levels in order to avoid the risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation in a situation where policy rates have reached their effective lower bound.

General considerations underlying the new phase of unconventional monetary policy

The launch of the new phase of non-standard measures in June 2014 must be viewed in the context of the decline in inflation rates since the second half of 2013, which was accompanied by persistently fragile euro area growth prospects, even after the sovereign debt crisis abated over the course of 2012. The economy was still in recession for most of 2013 and annual GDP growth figures only became positive in late 2013, leaving significant economic slack. A weak recovery took hold over the course of 2014 with growth rates around and below 1%, but the outlook deteriorated again during the autumn, with inflation turning negative later that year. The 2015 GDP growth forecasts for the euro area in the ECB staff macroeconomic projections had declined from 1.7% in June to 1% by December. At the same time, and in contrast to previous developments, weak growth was accompanied by a prolonged period of declining inflation, which went from 3% at the end of 2011 to -0.2% in December 2014. Credit supply conditions in the euro area remained tight, despite signs of improvement, as indicated by the responses to bank lending surveys. These developments were particularly worrying because they were accompanied by a decline in longer-term inflation expectations.

This combination of very low growth in both output and prices was clearly suggestive of a shortfall in aggregate demand and called for further easing of the monetary policy stance. Key ECB interest rates reached their lower bound – with a negative rate for the deposit facility – and further unconventional measures were deployed, drawing in part on the experience of other central banks. Besides lowering key interest rates in June and September 2014, which took the deposit facility rate into negative territory, the Governing Council has implemented the following set of unconventional monetary policy measures over the past year.

In June 2014, as part of a set of credit easing measures, the Governing Council announced the introduction of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), offering medium-term credit at fixed rates to banks that are willing to extend credit to the private sector.

In September and October 2014 the Governing Council initiated a programme of outright purchases of private sector assets, in particular of covered bonds and asset-backed securities.

In January 2015 the Governing Council expanded the purchase programme to include public sector assets. The Governing Council explicitly committed to purchasing a total amount of EUR 60 billion every month from March 2015 until at least until September 2016. Furthermore, the Governing Council has kept the programme open-ended by committing to keep it in place until we see a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation that is consistent with our medium-term inflation objective. The programme aims to maintain market neutrality by purchasing assets across the whole maturity spectrum between two and 30 years. The purchases are allocated across countries according to the ECB’s capital key and any losses emanating from the programmes would be shared between the national central banks and the ECB in an 80%/20% ratio.

The effects of the measures have to be assessed jointly and taking into consideration that some of the measures started to produce results before the decisions were actually taken. This is particularly true of the PSPP, which was adopted in January; a survey of market participants conducted in October 2014 showed that over 50% were already anticipating that such a programme would shortly be adopted.

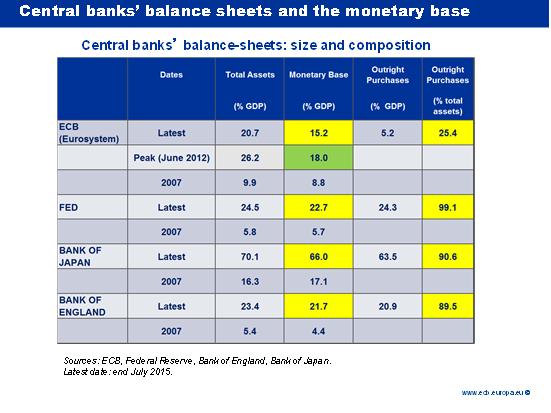

The distinguishing feature of the new phase of our unconventional monetary policy is the switch to a more active steering of the ECB’s balance sheet.

Figure 1

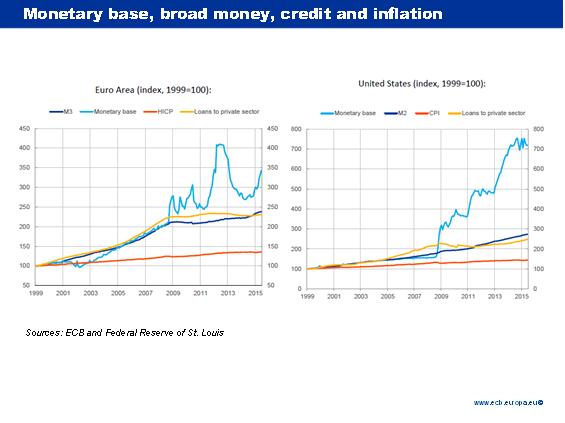

It is important to emphasise the nature of this new phase. Our intention is not to expand our monetary base in the expectation that, through the workings of a stable multiplier, this will result in an increase in monetary aggregates, which will in turn cause an upward movement in inflation by whatever means conceived by the traditional quantitative approach. Our main reason for adopting a large-scale asset purchase programme was to harness several new channels for the transmission of an expansionary monetary policy. The expansion in the monetary base and total balance sheet is rather a consequence of these new types of monetary stimulus. Recent experience shows abundantly that those traditional relationships are not working well in the new realities of the financial system (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

The first channel through which these new unconventional monetary policy measures are expected to stimulate aggregate demand is by signalling the ECB’s commitment to maintain an accommodative monetary policy stance. [1] The TLTROs are a particularly clear example of this signalling channel. With their pre-specified interest rate and their maturity extending over many years, these operations provided information on the likely path of future interest rates. In the case of asset purchase programmes, the signalling channel operates more indirectly, through the expansion of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet.

The second channel results in part from the first, and relates to the direct impact on medium-term inflation expectations that a LSAP programme implies. It is expected that when forming expectations about future inflation, market players factor in the effect of this non-standard policy measure.

Non-standard measures can also stimulate activity through a third channel, specifically by lowering the effective cost and availability of credit to the non-financial private sector. Again, the TLTRO programme does this, providing explicit incentives for banks to extend their credit supply. The effectiveness of this programme was reinforced by the conclusion of our comprehensive assessment of the quality of banks’ balance sheets in autumn 2014, which provided strong incentives for banks to speed up the repair of their balance sheets.

The fourth channel of transmission of the new unconventional monetary policy, which is specific to the asset purchase programmes, operates through portfolio rebalancing. By means of its purchase programmes, the ECB exchanges longer-term and relatively less liquid assets for very short-term and highly liquid central bank money. This mitigates liquidity and duration risks in private sector portfolios and, given liquidity and Value at Risk constraints, reduces the required compensation for holding risky and illiquid assets. [2] As a result, the programmes encourage portfolio rebalancing and support asset prices. The ensuing improvement in the balance sheet position of investors and banks eases leverage constraints and allows banks to extend more credit at lower costs to the private sector. [3] Better financing conditions improve growth prospects, increase profitability and mitigate default probabilities in the non-financial sector. These positive feedback effects further improve the condition of the balance sheets of investors and banks, and increase their willingness to extend new credit in a self-reinforcing positive spiral.

Evaluating the new phase of unconventional monetary policy

In order to correctly assess the effects of our policies, we should use what would have happened had we not adopted these measures as a benchmark for comparison. Of course, this is virtually impossible to do since there are no sufficiently reliable and complete models to construct the counterfactual world. We can only analyse how the variables related to the transmission channels or the end results have evolved since we started the new policy. This is what I will do below.

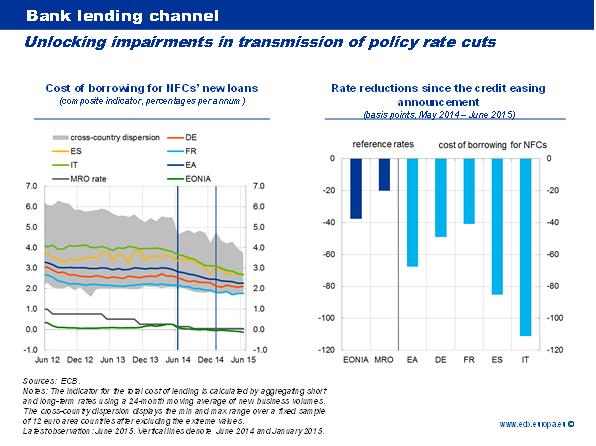

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows the evolution of lending rates in the euro area. It shows that the sequence of interest rate cuts implemented by the Governing Council between mid-2012 and mid-2014 was not transmitted to the effective borrowing costs faced by firms. By June 2014 we had cut the main refinancing operation (MRO) rate by 95 basis points, bringing it to 0.05%, down from 1% in June 2012. However, the decline in lending rates for loans in most countries was much smaller, with the median lending rate applied to small-sized loans in the median country having declined by not more than 30 basis points. Since June 2014 the transmission of policy rates to lending rates has improved considerably, with declines in lending rates becoming more pronounced as well as more widely distributed across euro area countries.

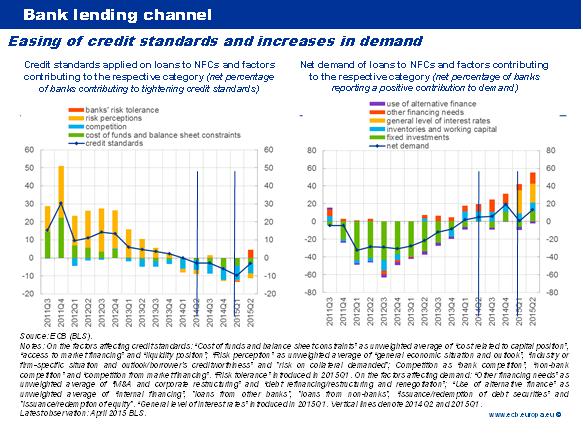

Figure 4

Our quarterly bank lending survey confirms the improvements in broader credit conditions since the introduction of our new non-standard measures. The survey, addressed to the senior loan officers of a representative sample of euro area banks, provides information on financing conditions in euro area credit markets and on banks’ lending policies. The left-hand chart in Figure 4 shows that banks have consistently eased their credit standards for loans to non-financial corporations over the past year. The easing of credit standards stems, notably, from the lower cost of funds and balance sheet constraints, as well as from greater competition among banks. Both developments were clearly objectives of our measures, in particular of the TLTROs. The right-hand chart in Figure 4 shows net credit demand conditions and their contributing factors. Easier access to credit has been coupled with a consistent increase in firms’ demand for loans. The general level of interest rates, according to the survey respondents, is contributing most to the recovery in loan demand.

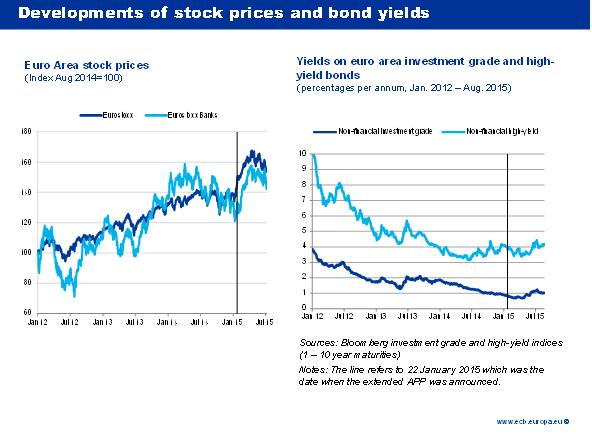

As I have already mentioned, an important transmission channel for asset purchases relates to the fact that different assets are imperfect substitutes. Consequently, interventions by the central bank that affect the supply of various assets available to private investors influence the prices of many other assets, including investment grade bonds, equities, real estate and foreign assets, with consequences for the exchange rate. Figure 5 shows the increase in equity and bond prices (the latter illustrated by investment grade corporate bond yields).

Figure 5

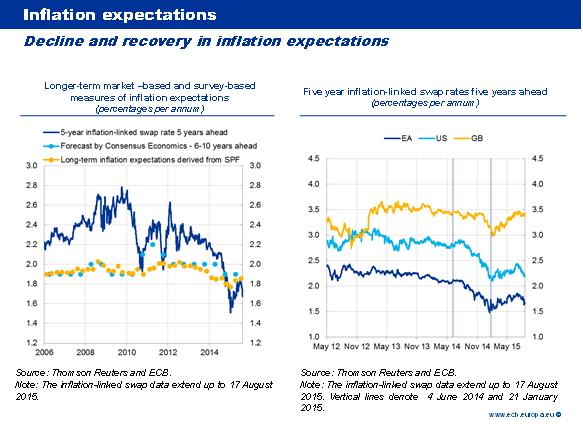

The ongoing deterioration of long-term inflation expectations was a major factor in the extension of our purchase programme in January this year. Figure 6 shows the evolution of these expectations over the past decade and since 2012. Euro area longer-term inflation expectations (both market-based and, to a lesser extent, survey-based) had been falling since early 2013, reaching an all-time low by early 2015.

Figure 6

Expectations of inflation five years ahead, as expressed in the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters, fell from 1.98% in the first quarter of 2013 to 1.77% in the first quarter of 2015. The five-year inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead fell from 2.4% to 1.5% over the same period. Since January 2015 this declining trend has been reversed. Both market-based and survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations have recovered from their lows. While broadly similar dynamics in market-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations have been observed in other countries, the decline in the euro area somewhat preceded them and was more prolonged.

I will now turn briefly to macro developments, both in terms of inflation and economic growth.

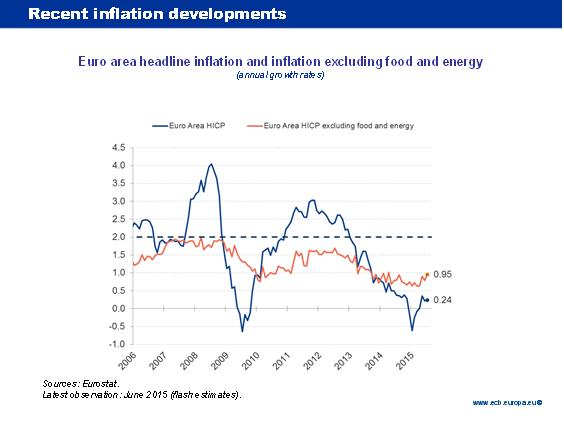

Figure 7

Since last April headline inflation has turned positive but remains very low, affected by the renewed decline in oil prices. Core inflation, excluding food and energy, continues however to firm, reflecting the ongoing economic recovery which is evolving in accordance with our baseline scenario. The latest round of our staff macroeconomic projections indicates that by 2017 inflation will be below, but close to, 2% and that GDP growth will also be hovering around 1.9%.

We do not deny that there are risks and shortcomings associated with the type of policies that we have been forced to adopt in view of our mandate to safeguard price stability in a symmetric way. Very briefly I will refer to several of these:

Medium-term inflation risks are very low and central banks have enough instruments to deal with them.

The exit strategy may involve the possibility of losses for the central bank. However, as Ben Bernanke has said, this is a possibility that, measured against the gains from a stronger economy and the previous contributions to government budgets, is “not a true social economic risk”. [4]

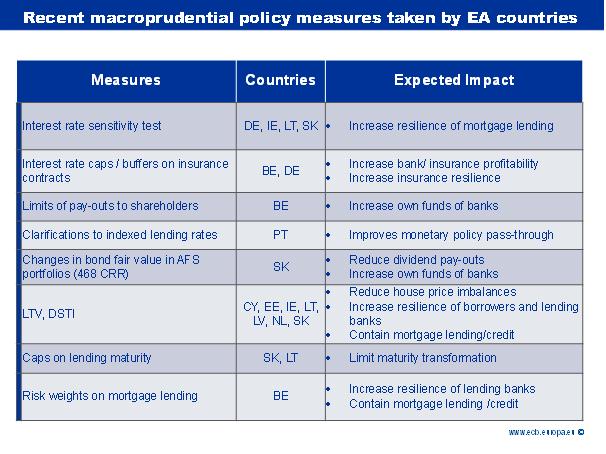

Financial stability risks, stemming from search for yield and higher leverage, are real, but monetary policy cannot be inhibited in the pursuit of its priority goals. Those risks must be addressed by macroprudential policies of a regulatory and administrative nature, and the policy toolkit available to central banks in this respect should be enlarged for that purpose.

Potential laxity of credit risk management by financial institutions in a climate of low rates. Supervision, appropriate risk management governance and the regulation of provisions should deal with this problem

Wealth effects and increased inequality. The stronger economy and lower unemployment that result from the LSAPs mitigate but do not eliminate this possible side effect.

Sometimes the criticism directed at our policies implicitly attributes responsibility for the low interest-rate environment to central bank policies. But the truth is precisely the opposite: central banks are simply reacting to and trying to correct a situation that they did not create. Indeed, medium and long-term market interest rates are mostly influenced by investors and market players, as the recent so-called “bund tantrum” illustrates. More importantly though, it should be pointed out that for a few decades now we have been witnessing a sort of secular trend towards lower real interest rates. This trend is related to secular stagnation in advanced economies, resulting from a continuous deceleration of total productivity growth and an increase in planned savings accompanied by less buoyant investment prospects. Monetary policy short-term rates are low because of those developments, not the other way around. At the same time, our monetary policy has to be accommodative precisely in order to normalise inflation and growth rates, thereby opening up the possibility of higher interest rates. Furthermore, in the present short-term conditions, with no fiscal room for manoeuvre, it is monetary policy that has the capacity to create the hope that this normalisation will protect savers in the future and improve net margins for banks.

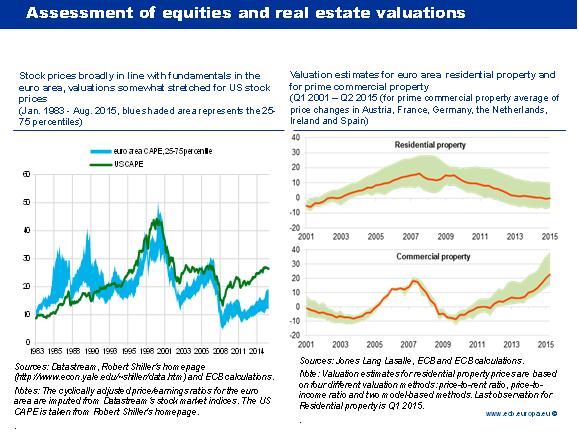

Regarding the risks associated with the search for yield and rich asset valuations, it is important to highlight that there are currently no signs of a general situation of asset overvaluation in the euro area. Figure 8 shows that in spite of the increase since the beginning of the year, equity prices are still fairly valued, with a Schiller cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio of 14, as against 26 in the United States. Likewise, real estate prices can also be shown to be broadly in line with fundamentals.

Figure 8

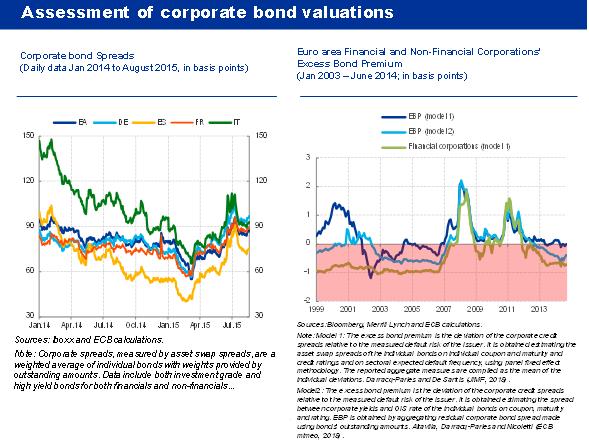

Corporate bond valuations are assessed as fairly valued or as only slightly overpriced, depending on the model used though, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9

Naturally, the heterogeneity of the euro area means that averages disguise different situations in member countries. In this respect, there are a few examples of higher pressure on housing or equity prices. The new competences of the ECB in the area of macroprudential policy ensure that, besides the initiative of national authorities themselves, a general assessment of developments in all euro area countries is made. Accordingly, the ECB could decide to use its own powers to trigger a tightening of macroprudential tools and to exert its coordinating role in relation to possible spillovers of the measures taken in particular countries. Macroprudential policy is active in the euro area, with dozens of macroprudential measures having been adopted in several countries, as Figure 10 illustrates.

Figure 10

Conclusions

Our new non-standard measures have successfully improved financial and credit conditions in the euro area and contributed to supporting the normalisation of price stability, as well as the ongoing economic recovery. I am confident that full implementation of the private and public sector asset purchase programmes, as announced, will lead to a sustained return of inflation rates towards levels consistent with our definition of price stability, underpinning the firm anchoring of medium to long-term inflation expectations. As always, the Governing Council stands ready to use all the instruments available within its mandate to respond to any material change to the outlook for price stability.

References

Bhattarai, S., Eggertsson, G.B. and Gafarov, B., “Time Consistency and the Duration of Government Debt: A Signalling Theory of Quantitative Easing”, unpublished manuscript, 2014.

Curdia, V. and Woodford, M., “The Central Bank Balance Sheet as an Instrument of Monetary Policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 2011.

Del Negro, M., Eggertsson, G.B., Ferrero, A. and Kiyotaki, N., “The Great Escape? A Quantitative Evaluation of the Fed’s Liquidity Facilities”, FRB NY Staff Report 520, 2011.

Eggertsson, G. and Woodford, M., “The Zero Bound on Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2002.

Gertler, M. and Karadi, P., “QE1 vs. 2 vs. 3: A Framework for Analyzing Large-Scale Asset Purchases as a Monetary Policy Tool”, International Journal of Central Banking, 2013.

Vayanos, D. and Vila, J.L., “A Preferred-Habitat Model of the Term Structure of Interest Rates”, NBER Working Paper 15487, 2009 .

Wessel, D. (ed.), Central Banking after the Great Recession: Lessons Learned and Challenges Ahead, Brookings Institution, 2014.

[1]See Eggertsson and Woodford (2003) and Bhattarai, Eggertsson and Gafarov (2014).

[2]See Del Negro, Eggertsson, Ferrero and Kiyotaki (2011) and Vayanos and Vila (2009).

[3]See Curdia and Woodford (2011) and Gertler and Karadi (2013).

[4]in Wessel, D. (ed.) Central Banking after the Great Recession: Lessons Learned and Challenges Ahead, Brookings Institution, 2014.

Banque centrale européenne

Direction générale Communication

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Allemagne

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction autorisée en citant la source

Contacts médias