Careful with (the "d") words!

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBThe European Colloquia Series Venice, 25 November 2008

1. Introduction [1]

First, I would like to thank the organisers of this session for having invited me here today to share with you my views on the economy, in Europe and worldwide.

In uncertain times, such as those we are currently living in, policy-makers must act with extreme caution. Economic agents and market participants listen to and read our words very carefully, in an effort to gain a better understanding of economic developments and possibly also to anticipate policy decisions. Under these circumstances, the safest thing for us to do would be to keep quiet, thus avoiding the emergence of misunderstandings which have the potential to affect the market. On the other hand, it is our responsibility to intervene in the policy discussions that are taking place in the current conjuncture, especially if we feel these discussions are taking the wrong track.

The issue that I would like to address here today has been raised in several quarters over the last few weeks. In my speech, I do not intend to attract more attention to it, but rather to react to what, in my view, has been an imperfectly informed discussion. It is important to make this clarification. When a policy-maker discusses an issue like deflation which – rightly so – raises emotional feelings, the reaction might be to ask: “why did he discuss such an issue?” Indeed, when the discussions on this issue began, in late 2002, markets reacted negatively. They probably thought that policy-makers were talking about deflation in order to prepare economic agents for it to happen.

My motivation is different. I would like to discuss the phenomenon of deflation because several observers, journalists, analysts and academics have started to talk about it in a way which, in my view, is imprecise. Referring to things in the right way, using the appropriate words – this should form the basis of any sound analysis. And this is what I would like to do today. It is not my intention to influence market expectations about future interest rate policy, but rather to explain how central banks analyse the economic situation and interpret data with a view to detecting risks of deflation. As I have already said in the past, it is much more useful for market participants to have a good understanding of the analytical framework supporting policy decisions, than for them to try to dissect each and every speech of the various members of the policy-making body to detect any indication of the next policy move.

One thing that I would like to emphasise from the start is that economic history has taught us that deflation risks should be considered objectively, rather than emotionally. On the one hand, the underestimation of deflation risks might ultimately lead to deflation. Overestimation, on the other hand, might sow the seeds of the next crisis.

2. What is deflation?

Deflation is defined as a decline in the level of prices, such as the consumer price index. This decline has three main characteristics: it is (i) generalised, i.e. it affects all prices; (ii) persistent, i.e. it lasts for some time, over several years; and (iii) expected by economic agents. It is often associated with a reduction in aggregate demand. An important indicator of a deflation is the self-perpetuating nature of the process. [2] The expectation of future price reductions induces households to postpone consumption and firms to reduce wage costs and delay investment, also in view of the higher rate of return. This depresses aggregate demand, which puts additional downward pressure on prices. The appreciation of the exchange rate might further exacerbate this tendency. A well-known example of a self-reinforcing price–income mechanism is Japan’s experience in the 1990s, also referred to as the “lost decade”.

A deflation triggered by a sharp fall in aggregate demand, possibly accompanied by unpredictable changes in economic sentiment (the Keynesian “animal spirits”), which induces producers to cut prices on an ongoing basis, is a serious cause for concern, particularly if it manifests itself in conjunction with a protracted economic slowdown and risks to financial stability. This can result in a self-perpetuating downward spiral, in which conventional economic policy options are severely restricted. The financial system may find itself in a situation not unlike the Keynesian “liquidity trap”, where private sector expectations that the nominal and real values of financial and real assets will fall lead agents to cling to any liquid, safe asset as tightly as possible.

These self-perpetuating effects may arise through various channels, such as via onerous debt burden, personal and corporate bankruptcies, financial crises or other adverse conditions. According to the “debt-deflation hypothesis”, first mentioned by Irving Fisher in 1933, falling prices increase the real debt burden and adversely affect firms’ balance sheets, which may result in a rising number of insolvencies and make banks more reluctant to grant loans. This leads to a further slowdown in investment, creating additional deflationary pressures. Furthermore, if consumers expect a further decline in prices and face excessively high and positive real interest rates, this may give rise to a general reluctance to purchase, causing a further decrease in aggregate demand and a further downward movement of the price level. In addition, in all cases on record, a sudden and sharp drop in asset prices, resulting in significant losses of wealth, has been a crucial factor in amplifying and propagating the initial disturbance. All the above-mentioned factors, sometimes in combination with policy failures, may add to the severity and length of the downturn.

3. What is not deflation?

Not all declines in the level of prices are deflation. First, individual prices can and do fall. In the euro area, for example, the price of computers has fallen substantially, which nobody has complained about. Even the overall consumer price index, such as the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area, can fall from time to time on account of seasonal factors as well as in the wake of significant changes in import or energy prices. The consumer price index might also fall if, following an exogenous shock, the equilibrium price level is lowered and the economy is flexible enough to adjust to this quite rapidly. I would call this adjustment disinflation, which can entail a temporary negative inflation in order for the price level to achieve its new equilibrium level. Disinflation can also be associated with negative growth in aggregate demand, at least temporarily. However, the quicker the adjustment of prices takes place, the lower the output cost of the adjustment will be.

The difference between deflation and disinflation is neither the possibility of a negative price change, nor the association with a fall in output. The difference is that, in a deflation scenario, expectations of price changes become negative and induce agents to postpone consumption and delay investment decisions. It is these negative inflation expectations that push the (ex ante) real interest rate up, above its equilibrium level, even when the nominal interest rate is brought down to zero.

What could push agents to expect negative inflation, thereby causing us to enter into a deflation scenario rather than a standard disinflation, is unclear. One possibility is that agents are not fully rational and form adaptive expectations. As they observe the start of the disinflation, since a negative inflation rate is then necessary to achieve the new equilibrium, they may think that this negative price change is likely to persist for some time. Negative inflation expectations might thus become entrenched. Given the zero bound on interest rates, the negative inflation pushes real rates up, thereby adding recessionary forces to the economy, which might add fuel to the price declines.

Another hypothesis is that the disinflation process is not quick enough to stabilise the economy at the new equilibrium. As in the case of asset markets that do not function properly, when the equilibrium price is not achieved rapidly enough and the adjustment process is slow, the price dynamics will take longer and might even overshoot, generating destabilising patterns. The same could occur for the real economy, as a lack of flexibility in the markets delays the adjustment of the price level, thus generating negative expectations. This scenario might be aggravated if policies aim to stabilise the economy at the “wrong” equilibrium, thereby delaying adjustment towards the new equilibrium. I would conjecture that the more the economy is kept away from its equilibrium, the more the adjustment, in terms of prices and output, might become non-linear. This could happen especially if the classical transmission mechanisms of monetary and fiscal policies are impaired, owing to a loss of confidence in the financial system, for instance. More work needs to be done in this field, in particular in order to gain a better understanding of how price expectations are formed in the face of a negative demand shock.

4. Detecting deflation

Although we have experienced deflation in the past, these experiences have been quite rare. Most of us would immediately think of the deflation during the Great Depression, and the recent occurrence in Japan. The sustained deflationary episodes of the Great Depression in the 1930s and those in Japan in the second half of the 1990s have some underlying factors in common. Both episodes followed long periods of exceptionally optimistic views on potential output and major speculative stock price and asset price bubbles. In both cases, exchange rate appreciation contributed to increasing deflationary pressures. However, there are also obvious differences between the two episodes. Monetary policy clearly had a more damaging impact in the United States. As shown by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz already long ago, the initial downturn in August 1929 and the Great Depression that followed were mostly due to restrictive monetary policy, which added substantial fuel to the rapid and strong decline in demand. From August 1929 to March 1933 the real gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States fell by almost 30%, or 7.6% on a yearly average. Similar drastic declines in average annual output also occurred in other countries, for example, in Canada (-8.4%), Germany (-2.7%), United Kingdom (-1.0%) and France (-2.2%). This contraction was transmitted to the rest of the world via the fixed exchange rate linkages of the gold standard and by “golden fetters” which prevented the monetary authorities of gold standard adherents from following the expansionary policies needed to offset the collapsing demand and a rash of banking panics across the world (Bernanke and James (1991)), without triggering a speculative attack on the gold parity (Eichengreen (1992)).

Monetary conditions also played a role in the case of Japan. With hindsight, it could be argued that the monetary policy was overly accommodating during the creation of the bubble, and possibly too tight as the recession started in 1991. In any case, it is now obvious that deflationary risks were not recognised at the time. Furthermore, weakness in the supervisory system and ingrained practices in the banking sector prevented the economy from resolving the problem of non-performing loans, with lasting implications for the recovery of output. Although the price level decline in Japan led to a protracted slump, it was still considerably weaker than the fall in prices in most countries during the Great Depression. The inflation rate fell below zero in 1995 and then remained negative until 2005, averaging 0.1% per annum. However, overall production did not suffer as much during this period. GDP growth came to a standstill in 1992-93, declining from its previous peak of above 5% in 1990. Between 1995 and 2007 Japan’s per capita GDP grew at an average yearly rate of only 1.2%, against 1.8% in the euro area and 1.9% in the United States.

Looking at the current situation, inflation reached a peak just a few months ago. In July inflation in the United States hit 5.6%, the highest rate since 1991. In the same month inflation in the euro area surged to 4% and, in September, consumer price inflation hit 5.2% in the United Kingdom. These high inflation rateswere mainly the result of the surge in commodity prices in the first half of the year. Since then global economic growth has slowed down sharply and the commodity boom has turned into a bust. The price of a barrel of crude oil has dropped sharply, from a peak of USD 147 per barrel in July to below USD 50 per barrel in recent days. Against this background, the latest releases have shown a significant decline in inflation rates, though in most countries they remain above the respective medium-term objectives for price stability. According to the data, there is clearly no country in deflation right now.

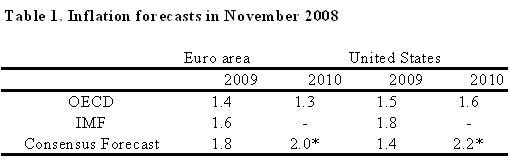

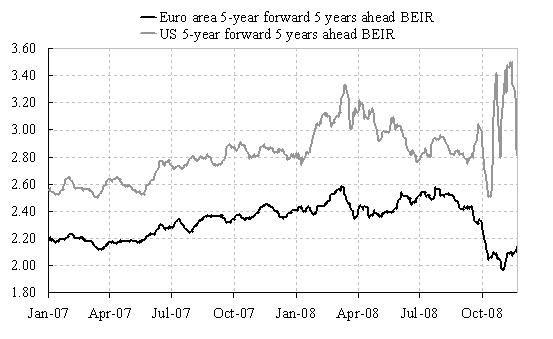

Looking ahead, the inflation outlook is bound to change substantially. If raw material prices remain at their current levels, the year-on-year change in the energy-related component of the consumer price indices will turn sharply negative in many countries in 2009. As a result, global inflation can be expected to drop quickly over the next few months, but it should remain in positive territory. For the euro area, the latest inflation forecasts for 2009 are as follows (see Table 1): 1.4% from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 1.6% from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and 1.8% from Consensus Economics. For 2010, many forecasts foresee a rise in inflation in the euro area, except for the forecast of the OECD at 1.3%. Consensus Economics projects inflation at 2.0%. To my knowledge, no individual private sector analysis or forecast is projecting deflation in the euro area either; this is true, in particular, for the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters. The longer term expectations for inflation, as measured by the five-year forward five years ahead break-even inflation rate derived from inflation-linked bonds, hover around 2%. Moreover, the available forecasts and expectations do not foresee any material risk of deflation in the United States either.

Overall, while a number of factors suggest that inflationary pressures will decline significantly, there are currently no signs of any deflationary expectations. As long as inflation expectations remain firmly anchored, deflation will remain a rather remote risk.

5. Deflation and monetary policy: strategy and implementation

In recent years we have acquired considerable knowledge on the causes, nature and dynamics of deflation. The insights we have gained, including recognising that our knowledge is imperfect, are invaluable for policy-makers. I will now conclude by summarising the pertinent issues for monetary policy.

How can central banks prevent, or at least minimise, deflation risks and how can they effectively counter such risks if they materialise? By using an appropriate strategy to anchor expectations and taking robust decisions, by employing policy instruments in an effective and credible manner and by ensuring that the markets and the public at large are fully informed of and understand the central banks’ intentions and actions. Of course, the conduct of monetary policy should always be characterised by these elements but, in terms of preventing and counteracting the risk of deflation, they become indispensable. Let me now examine each of them in turn.

The ability of the monetary authorities to anchor expectations to their objective of price stability is crucial and can be considered a first line of defence against deflation risks. The anchoring of inflation expectations can be greatly facilitated by a quantitative specification of the objective of price stability. In choosing this quantitative objective, due consideration should be given to, among other things, potential deflation risks. When the European Central Bank (ECB) evaluated its monetary policy strategy in 2003, it confirmed its quantitative definition of price stability. At the same time, it clarified that, in the pursuit of price stability, it will aim to maintain inflation rates close to but below 2% over the medium term. This clarification was partly meant to underline “the ECB’s commitment to provide a sufficient safety margin to guard against the risks of deflation” and also to “address the issue of the possible presence of a measurement bias in the HICP and the implications of inflation differentials within the euro area”. The quantitative definition of the monetary policy objective can help to make expectations of future price developments “mean-reverting”, thus ensuring that they do not depart from the central bank’s stated objective. Needless to say, the ability of the central bank to anchor expectations ultimately depends on how effective it is at achieving its goal.

This requires, especially in an environment of low inflation and low interest rates, the central bank to use a strategy which provides a robust basis for decision-making and an effective framework for communicating policy decisions. A robust strategy is one that can be expected to work well enough under different assumptions concerning the channels and dynamics of the monetary transmission mechanism, including alternative hypotheses regarding the type and degree of nominal rigidities and the nature and formation of expectations.

The ECB’s strategy combines economic and monetary analysis in assessing the outlook for price stability and the associated risks. It is suited to the conduct of monetary policy in an environment of low inflation. Monetary analysis not only serves to “cross-check”, from a longer term perspective, the assessment based on the economic analysis, which focuses on a short to medium-term horizon; it can also provide useful information on the evolution of asset prices and help signal misalignments in the asset markets that – if left unchecked – may unwind in a disorderly way. [3] A robust approach to assessing the risks surrounding the economic outlook can insure against taking no action or making decisions too hastily, which can both be regretted with hindsight. In this respect, historical evidence supports the conclusion that monetary aggregates can play an important role when inflation is low or negative and the nominal interest rate is constrained by the zero lower bound. [4]

With regard to policy implementation, the old saying that “prevention is better than cure” is also applicable when concrete deflation risks emerge. The potentially complex deflation dynamics suggest that the central bank should act promptly and, possibly, in a pre-emptive fashion. By acting decisively and early, the central bank can reduce the probability that the zero interest rate will become a binding constraint and that conventional monetary policy will become ineffective. A swift easing of policy may also help to stabilise asset prices, counter a disproportionate widening in the market risk premium and thus prevent a sharp decline in the provision of credit.

However, such an approach, aimed at insuring against a possible deflation risk, does come at a cost. First, it may contribute to, rather than obviate, a worsening of market sentiment if it is interpreted as a signal that the central bank has made a more pessimistic assessment of the economy than market participants. In the past, sharp reductions of policy rates have been found to lead to a deterioration of market sentiment. A policy of insuring against a deflation risk, without clear evidence that the risk is actually materialising, might in fact create a focus for agents’ expectations of negative inflation, thus increasing its likelihood. Second, if the transmission of monetary policy does not function properly, the lowering of policy rates is not transmitted to the real economy and is thus not effective. We can see that, in the current environment, rates offered to end users have fallen much less than policy rates. This undermines confidence in the effectiveness of monetary policy, which might aggravate the problem. Therefore, it is preferable to devote efforts to improving the transmission mechanism, in particular by strengthening the solvency situation of the banking system. Third, if all ammunition is exhausted earlier in the process, before there is any evidence of a deflationary shock, this reduces the room for manoeuvre in case other adverse shocks occur. For instance, if foreign exchange markets do not display a major appreciation of the exchange rate, which in the past has always been associated with deflation, monetary policy should maintain some room to counter this undesired development if it were to occur in the future. Finally, if deflation risks eventually subside, too loose a monetary policy stance can fuel excessive risk taking, which can then give rise to a new asset bubble, leading to even greater problems. Allow me now to spend a few moments considering this issue.

The counterargument is that the real problems caused by lowering rates would emerge if rates were kept at low levels for too long, something central banks have been reproached for in the first half of this decade. To avoid this scenario, the solution is not to avoid cutting rates to a low level in the first place, but to raise them quickly enough when the deflation fears evaporate. However, this strategy is not time consistent. In order to be credible, a policy of low interest rates aimed at insuring against a deflation risk must affect the whole yield curve. This requires the central bank to commit to maintaining low rates for a prolonged period of time. [5] This is the only way to create the incentive to invest in risky assets rather than holding on to money. However, the longer interest rates are held at a low level, below the equilibrium level, the greater the need for a quick tightening to reverse the course and bring the policy back in line. Such a tightening would induce a substantial repricing of risk, however, and a potential downloading of these risky assets from investors’ portfolios. The more agents have accumulated risky assets on the expectation that rates will remain low, the more the decision to finally increase policy rates will produce some disruption in asset markets. The experience of 1994 is quite interesting in that respect. Thus there is a natural tendency to postpone the decision to tighten policy until there is clear evidence that a solid recovery is taking place. Raising rates too early would be feared to be jeopardising this recovery. Meanwhile, the more the rate increase is delayed, the sharper it should be to catch up on lost ground, [6] although a similar problem to the one just explained would still emerge. To avoid creating turbulence, the tightening tends to be conducted at a measured pace, which inevitably leads policy to be behind the curve.

To sum up, if interest rates are pushed very low for fear of deflation and then this deflation does not materialise, sooner or later market participants will have to shed the risky assets that they accumulated in their portfolios as a result of this low level of rates and account for capital losses. Monetary policy might postpone the timing of such portfolio reallocation, keeping rates low and thus maintaining the incentive to avoid capital losses, but at a certain point it will become unavoidable. The inclination could be to postpone it as long as possible, but the risk then is that when the adjustment finally comes, on top of other adjustments in the economy, its effects could be very disruptive. This story might sound familiar. It should encourage prudence in the conduct of “insurance” policies. Although they might sound costless in the short term, the bill might then come when least expected, and with a surcharge.

6. Conclusions

In my opinion, the term “deflation” is often misused as a catch-all phrase to describe every kind of negative development. This can obviously be dangerous, as it could lead to the wrong policy advice, much like a wrong diagnosis may lead to the prescription of an overly aggressive medical treatment. The patient may think that this is harmless, and costless if he is insured. But, as doctors know, there is no benign medicine and patients are always invited to carefully read the list of side effects and possible complications.

The best contribution that monetary policy can make to avoiding the negative scenarios that I have described today is to be implemented within a framework that ensures both a clear definition of price stability and a medium-term strategy in which the relevant economic and financial indicators are taken into account. This is the way the ECB has conducted monetary policy, also in turbulent times. But this is not sufficient. It is essential that the transmission mechanism of monetary policy is improved, so that the monetary impulse is transmitted effectively to the real economy. This requires decisive action, in particular by national governments, to ensure the solidity of the financial system and restore confidence in financial markets.

* This refers to the first two quarters of 2010, as reported in the survey in September 2008.

Figure 1. Five-year forward five years ahead break-even inflation rates in the euro area and the United States

(Five-day moving averages of daily data; as percentages per annum)

Source: Bloomberg and ECB calculation.

References

L. Benati, “Investigating Inflation Persistence Across Monetary Regimes”, Quarterly Journal of Economics , No 123(3), 2008, pp. 1005-1060.

B. Bernanke, “Deflation: Making Sure “It” Doesn’t Happen Here”, Remarks before the National Economist Club, Washington DC, 21 November 2002.

L. Bini Smaghi, “Three Questions on Monetary Tightening”, Nomura Conference, 26-27 October 2006. Available at: www.ecb.int.

M. Bordo, C. Erceg and C. Evans, “Money, Sticky Wages and the Great Depression”, American Economic Review, 2000.

M. Bordo and A. Filardo, “Deflation and Monetary Policy in a Historical Perspective: Remembering the Past or Being Condemned to Repeat It”, Economic Policy, Vol 20(44), 2005, pp. 799-844.

M. Bordo, J. Landon Lane and A. Redish, “Good versus Bad Deflation: Lessons from the Gold Standard Era”, NBER Working Paper No 10329, National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2004.

C. Borio and P. Lowe, “Asset Prices, Financial and Monetary Stability: Exploring the Nexus”, BIS Working Paper No 114, Bank for International Settlements, 2002.

J. Bradford De Long and L. Summers, “Is Increasing Price Flexibility Stabilising?” American Economic Review, No 76(5), 1986, pp. 1031-1044.

L. Christiano, R. Motto and M. Rostagno, “The Great Depression and the Friedman-Schwartz Hypothesis”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, No 35(6), Part 2, December 2003, pp. 1119-1197.

C. Goodhart, “Beyond Current Policy Frameworks”, BIS Working Paper No 189, Bank for International Settlements, 2004.

O. Issing, “Central Bank Perspectives on Stabilization Policy”, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, Vol. 87(4) (fourth quarter), 2002.

J. M. Keynes, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”, London, McMillan, 1936.

S. Kuroda and I. Yamamoto, “The Impact of Downward Nominal Wage Rigidity on the Unemployment Rate: Quantitative Evidence for Japan”, IMES Discussion Paper No 2003-E-12, 2003.

-

[1] I thank L. Dedola, K. Forster, C. Kamps and M. Rostagno for their input into the preparation of these remarks.

-

[2] A mere decrease of prices of some categories of goods, in individual sectors or in certain regions should also not be termed deflation. In a market economy, such relative price adjustments are a response to changes in supply and demand – for example, differences in sectoral productivity developments – and are essential for an efficient welfare-enhancing allocation of resources. Deflation per se only occurs when price declines are so widespread that broad-based indices of prices register ongoing declines. This is particular relevant for the euro area, as the consequences of deflation in the whole area would also be very different from a decline in prices in any individual euro area country (Issing (2002)).

-

[3] See O. Issing (2002) and C. Borio and P. Lowe (2002).

-

[4] See M. Bordo and A. Filardo (2005).

-

[5] See B. Bernanke (2002).

-

[6] See L. Bini Smaghi (2006).

Banque centrale européenne

Direction générale Communication

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Allemagne

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction autorisée en citant la source

Contacts médias