Substitution between debt security issuance and bank loans: evidence from the SAFE

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2023.

This box investigates whether the recent deterioration in bond market financing conditions incentivises firms to substitute bond issuance with bank loans, and whether this substitution affects lending to other firms. As monetary policy has gradually been normalised, the financing costs of firms have been rising. In the latest round of the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), euro area firms reported that their need to issue bonds increased by more than the demand for such bonds by investors, resulting in a broad-based increase in corporate bond financing gaps. Although relatively few firms in the SAFE issue bonds (around 9% between 2009 and 2022) compared with the number of those using banking products (slightly over 50%), a deterioration in bond market financing conditions could have broader implications for bank lending conditions for firms.[1] Since bond issuers are usually larger firms that are able to substitute towards other sources of financing, particularly to bank loans, such substitution may negatively affect lending to other firms that have no access to the corporate bond market.[2] This box thus reviews the main characteristics of euro area bond issuers, investigates whether they substitute bond issuance with bank loans as bond market conditions worsen, and explores whether a deterioration in bond market conditions within euro area countries is associated with a deterioration in bank lending conditions for SMEs.

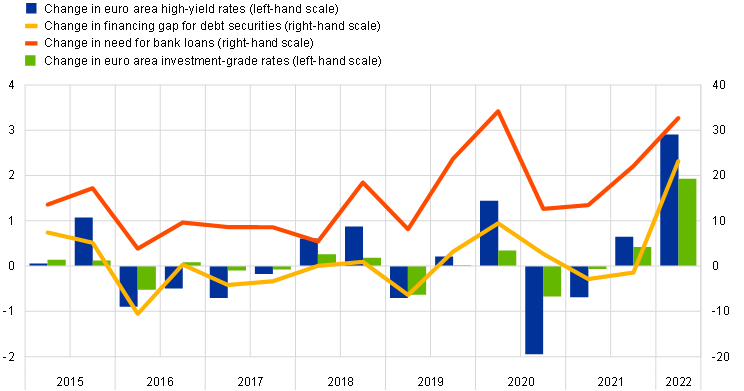

Amid the ongoing monetary policy normalisation, euro area firms reported a widening of their debt securities financing gap, which has historically been associated with higher demand for bank loans (Chart A). Amid the ongoing normalisation of monetary policy, corporate bond yields increased significantly during the latest SAFE round (covering April to September 2022) – both in absolute terms and relative to other sources of debt financing for firms.[3] Historically, an increase in corporate bond yields tends to correlate with a widespread increase in financing gaps for corporate bonds reported in the SAFE (Chart A). Additionally, the net share of firms reporting an increase in their corporate bond financing gap and the net percentage indicating an increased need for bank loans tend to move in tandem, possibly indicating that firms consider the two sources of financing to be substitutes for each other. Consistent with this, while a net 29% of firms issuing bonds reported an increase in their financing gap for debt securities during the last survey wave, a net 32% of bond issuers reported an increased need for bank loans. Looking at aggregate volumes, corporate bond issuance declined during 2022, while credit growth to firms started to slow down as well.[4]

Chart A

Changes in financing gap for debt securities, demand for bank loans and corporate bond yields

(percentage points (left-hand scale) and net percentages of firms)

Source: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE) and IBOXX.

Notes: Net percentage of firms indicating an increased financing gap for debt securities and an increased need for bank loans in the SAFE. Only firms reporting bank loans and debt securities as a relevant source of financing are included. The changes in euro area corporate bond yields are based on the average yield over the survey rounds, each covering six months.

Corporate bonds are more often issued by larger and profitable firms, which tend to have a more diversified funding structure. Based on a probit model, Chart B shows how different firm characteristics relate to the probability of issuing corporate bonds.[5],[6] As shown in the chart, being a medium or large company is an important characteristic of bond issuers. In fact, the average medium or large firm (with more than 50 employees) issues corporate bonds 4 percentage points more often than smaller-sized firms. Firms that report a recent increase in profits, growth in investment or employment likewise tend to issue bonds more often than others. Additionally, firms counting on an additional source of financing are, on average, 4 percentage points more likely to rely on corporate bond issuance, implying that bonds are usually not the only source of finance.[7] Firms with a diversified funding structure avoid over-reliance on bank lending, as they can substitute it with other sources of financing – particularly with corporate bonds. This is beneficial, especially during a credit crunch or an intensified period of bank risk aversion as in the global financial crisis.[8]

Chart B

Marginal impacts of firm characteristics on whether firms issue debt securities

(average marginal effects with 95% confidence bands)

Source: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), ECB calculations.

Notes: Average marginal effect on issuance of debt securities, based on probit regressions, of a change from 0 to 1 in dummy variables that only take those two values and a unit change in the variable measuring the number of financial instruments. The dependent variable is a dummy equal to 1 if firms report debt securities as a relevant source of finance and have used them as such. The regression includes five explanatory dummy variables, each of which is equal to 1 if firms reported that they had, respectively: (1) more than 50 employees (medium-large), (2) past increases in profits, (3) past increases in investment in fixed assets, (4) past increases in working capital and (5) past increases in employees. The degree of funding diversification is measured by the number of financial instruments used by the firm (from one to eight). Sector, country and time fixed effects are included in all specifications. Results are weighted to ensure representativeness. The bands shown are 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered by country. The sample includes all rounds of the SAFE, covering the period March 2009 to September 2022.

Bond-issuing firms tend to substitute bond issuance with bank loans as corporate bond market conditions deteriorate, as measured by increasing financing gaps for bonds in the SAFE. The recent widening of the debt securities financing gap and the increased demand for bank loans by bond issuers could indicate substitution between financing instruments. In a similar vein, euro area banks reported that, especially for large firms, the substitution away from debt securities increased the demand for bank loans in the second and third quarter of 2022.[9] To study the substitution between bond issuances and bank loans, only firms reporting both sources of financing as relevant in the SAFE are considered. A probit model is used to estimate the effect of a rise in bond financing gaps on the probability that firms report an increased need for bank loans.[10] To ensure that the results are not driven by particular periods, the sample is split into five distinct phases of the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP) and pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), which also coincide with shifts in the overall monetary policy stance. These are: (1) before the APP (March 2009 to September 2015), (2) before the slowdown in net purchases under the APP (October 2015 to September 2018), (3) during the slowdown in net purchases under the APP (October 2018 to September 2019), (4) during the PEPP (October 2019 to March 2022) and (5) end of net purchases (April to September 2022).[11] For all sub-periods, the estimated substitution effects are statistically significant and positive: firms report an increased need for bank loans when their financing gaps for debt securities widen. While the substitution effect is estimated to be weaker during periods of higher net purchases under the ECB’s asset purchase programmes, i.e. (2) and (4), it is significantly higher only in the most recent period, end of net purchases (5). The differences in the estimated degrees of substitution could indicate that the substitution by firms away from bonds may depend on sufficiently adverse changes in bond markets. Large net asset purchases by the ECB support an improvement, or at least limit a deterioration, in bond market conditions, potentially causing fewer firms to substitute bond issuance with bank loans.

Chart C

Effect of an increase in bond financing gap on need for bank loans at the firm level, by sub-periods

(average marginal effects with 95% confidence bands)

Source: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), ECB calculations.

Notes: Sub-period specific average marginal effects of an increase in a firm’s debt securities financing gap on the probability that the firm’s need for bank loans increases. The effects are based on a probit model in which the dependent variable is equal to one if a firm reports an increased need for bank loans, with the regressors being the direction of change in the firm’s financing gap for bonds, in the firm’s availability of bank loans and in the firm’s profitability (where a value of 1 indicates an increase, 0 indicates no change and -1 indicates a decrease in the respective measure). The model also includes firm size, sector, country and time fixed effects. The data are reweighted to ensure representativeness. The coefficients on the change in the financing gap are sub-period specific (by means of interaction with sub-period specific dummy variables), where the sub-periods considered are before the APP (March 2009 to September 2015), before the slowdown in net purchases under the APP (October 2015 to September 2018), during the slowdown in net purchases under the APP (October 2018 to September 2019), during the PEPP (October 2019 to March 2022) and end of net purchases (April to September 2022). The bands shown are 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered by country.

A widening of the corporate bond financing gap in euro area countries is associated with worsening bank lending conditions for SMEs, which could be due to crowding-out effects (Chart D). The substitution towards bank loans by corporate bond issuers could have broader implications if their increased demand crowds out lending to other firms, such as SMEs. While it is difficult to empirically isolate crowding-out effects, the reduced-form relationship between changes in the country-level corporate bond financing gap and bank lending conditions of individual SMEs in the same country, as estimated here using a probit model, provides an indication.[12] The model is estimated using three different dummy dependent variables: (1) bank loan availability, (2) banks’ willingness to lend, and (3) bank loan interest rates. The dummy variables equal one if the individual firm reported an increase and zero otherwise. In each case, the model suggests a statistically significant relation between the country-level corporate bond financing gap and bank lending conditions for SMEs. A broad-based increase in the country-level financing gap for corporate bonds of 10 percentage points, as measured in the SAFE, implies that SMEs in that country are 0.4 percentage points less likely to report an increase in bank loan availability and 0.7 percentage points less likely to report an increase in banks’ willingness to lend.[13] At the same time, a similar increase in the country-level financing gap for bonds is associated with a higher probability of 0.8 percentage points that SMEs report higher bank loans rates. These effects are economically sizeable: in the last SAFE round, the corporate bond financing gap increased by a net 25 percentage points for firms also relying on bank loans. Based on the estimates above, this would be associated with changes in the share of SMEs reporting increased availability of bank loans, banks’ willingness to lend, and bank loan rates of roughly -1 percentage point, -1.75 percentage points and 2 percentage points, respectively. This corresponds to around 5%, 8% and 7% of the respective sample means. While these findings could be driven by the general development in financing conditions (simultaneously affecting bond market and bank lending conditions), they suggest that deteriorations in corporate bond market conditions have implications for firms not issuing bonds. In a similar vein, several papers have found that the ECB’s corporate sector purchase programme also benefited firms that do not issue bonds, as banks’ lending constraints are relaxed when bond issuers substitute away from bank lending.[14] Indeed, the deterioration in corporate bond markets might also be contributing to the tightening in bank lending conditions for firms.

Chart D

Effect of a wider country-level bond financing gap on bank lending conditions for SMEs

(average marginal effects with 95% confidence bands)

Source: ECB and European Commission Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), ECB calculations.

Notes: Average marginal effect of a unit increase in the country-level financing gap for debt securities (the difference between the change in demand and change in supply) on bank lending conditions reported by SMEs based on probit regressions. The country-level financing gap for debt securities is calculated as a weighted average of firms that consider both debt securities and bank loans relevant. The model is estimated using three different dependent variables: (1) availability of bank loans, (2) banks’ willingness to lend and (3) bank loan interest rates. In all cases, the dependent variable is a dummy equal to 1 if firms reported an increase. The model is estimated for SMEs that consider bank loans to be a relevant source of financing, but not bonds. The model controls for the change in the need for bank loans and the change in profit reported at firm-level, as well as dummies capturing country, sector and survey wave. The bands shown are 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered by country. The sample includes all SAFE waves, covering the period from March 2009 to September 2022.

In this box, a deterioration in corporate bond market conditions is defined as a widening of the debt securities financing gap (difference between the change in demand for and the change in the supply of debt securities financing) as reported by firms in the SAFE.

See “Taxonomy of financing patterns of euro area SMEs and real effects” in “Non-bank financial intermediation in the euro area: implications for monetary policy transmission and key vulnerabilities” Occasional Paper Series, No 270, ECB, revised December 2021.

See Section 5, “Financing conditions and credit developments”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2022.

See “Monetary developments in the euro area: November 2022”, press release, ECB, 29 December 2022.

Besides individual firm characteristics, the development of a country’s financial system and economic growth are often positively related to the use of market-based finance, see De Jong, A., Kabir, R. and Nguyen, T., “Capital structure around the world: The roles of firm- and country-specific determinants”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 32, Issue 9, pp. 1954–1969, September 2008.

The econometric specification is described in detail in the notes to Chart B.

In the SAFE, firms indicate that they rely on retained earnings, bank loans, bank overdrafts, leasing/factoring, subsided loans, trade credit, debt securities and equity, in order of importance. The likelihood of issuing corporate bonds increases with the degree of diversification. In fact, the probability of using corporate bonds becomes much higher when firms report more than four different financial instruments, jumping to 8 percentage points and to 14 percentage points with five and six different sources of finance respectively.

See for further evidence “Firm debt financing structures and the transmission of shocks in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2022.

See “The euro area bank lending survey – Third quarter of 2022”, ECB, October 2022, and “The euro area bank lending survey – Second quarter of 2022”, ECB, July 2022.

The econometric specification is described in detail in the notes to Chart C.

Note that each round of SAFE covers six months, which must be assigned to the same subsample period. The period “end of net purchases” hence covers April to September 2022, although net asset purchases were concluded in July 2022.

The country-level financing gap for corporate bonds is calculated as a weighted average for those firms that consider bonds and bank loans to be a relevant source of financing. The probit model is estimated for SMEs reporting bank loans to be a relevant source of financing, but not corporate bonds.

The financing gap of an individual company takes the value 1 (-1) if the need of debt securities increased (decreased) while availability decreased (increased). Firms can also report no change (0). Hence, a 10-percentage point change in the country-level financing gap corresponds to a net 10% more of bond issuers reporting a larger need for, and lower availability of, debt securities.

See, for example, Betz, F. and de Santis, R. A., “ECB corporate QE and the loan supply to bank dependent firms”, Working Paper Series, No 2314, September 2019 and Arce, Ó., Gimeno, R. and Mayordomo, S. (2021b), “Making room for the needy: the credit reallocation effects of the ECB’s corporate QE”, Review of Finance, Vol. 25, Issue 1, February 2021, pp. 43-84.