- SPEECH

A commitment to the recovery

Speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Rome Investment Forum 2020

Rome, 14 December 2020

2020 has been a year like no other. We have faced an economic contraction without precedent in peacetime: in the first half of this year output in the euro area declined by more than 15%. But we have also seen a collective response that has no precedent in the history of our monetary union.

That response has protected our economy from a potentially catastrophic depression. And now, with positive news on vaccines, we are finally able to glimpse the light at the end of the tunnel.

But we still need to pass through the tunnel. 2021 will likely be a “pandemic year”, characterised by high uncertainty and widespread vulnerabilities among firms and households. How the European economy emerges from the crisis will depend on how we manage this transition.

So what I would like to argue today is that policymakers must commit to continue providing certainty to the economy. The end of the pandemic is now in sight, and we need to extend policy support in order to underpin the recovery.

But expansionary policies must not be wasted. Only by taking the opportunity to invest in Europe’s recovery can we re-emerge on the other side with a more dynamic economy and a more sustainable debt burden.

A common shock, a common response

The coronavirus (COVID-19) is a common shock that has had asymmetric effects[1], hurting some sectors and economies much more than others. But what has defined this crisis – and set it apart from previous ones – is the policy response at the European level and the recognition that a common shock requires a common response.[2]

From the outset, monetary and fiscal policies have reinforced each other. The ECB has taken forceful monetary policy measures to stabilise markets and prevent a tightening of financing conditions. And fiscal policy has empowered monetary policy by offsetting lost private sector income and enabling banks to support the real economy. European policies – the ECB’s monetary policy and the joint EU fiscal support – have generated a European dividend.

This was a step change in European crisis management. As a result, the euro area economy was able to stage a strong rebound over the summer, as containment measures were lifted.

However, the recovery has been temporarily suspended in recent months due to the resurgence of the pandemic. Eurosystem staff now project that the euro area economy will contract by more than 2% in the fourth quarter of this year, with GDP falling by 7.3% overall in 2020. Growth next year will be 3.9%, 1.1 percentage points lower than expected in September.

Inflation will remain subdued for a protracted period: it is currently negative and is projected to rise to just 1.1% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023; excluding its more volatile components, it is expected to increase to only 1.2% in 2023. This inflation weakness reflects the significant demand gap that the economy will be facing in the next two years. And – of relevance to today’s forum – this has implications for business investment.

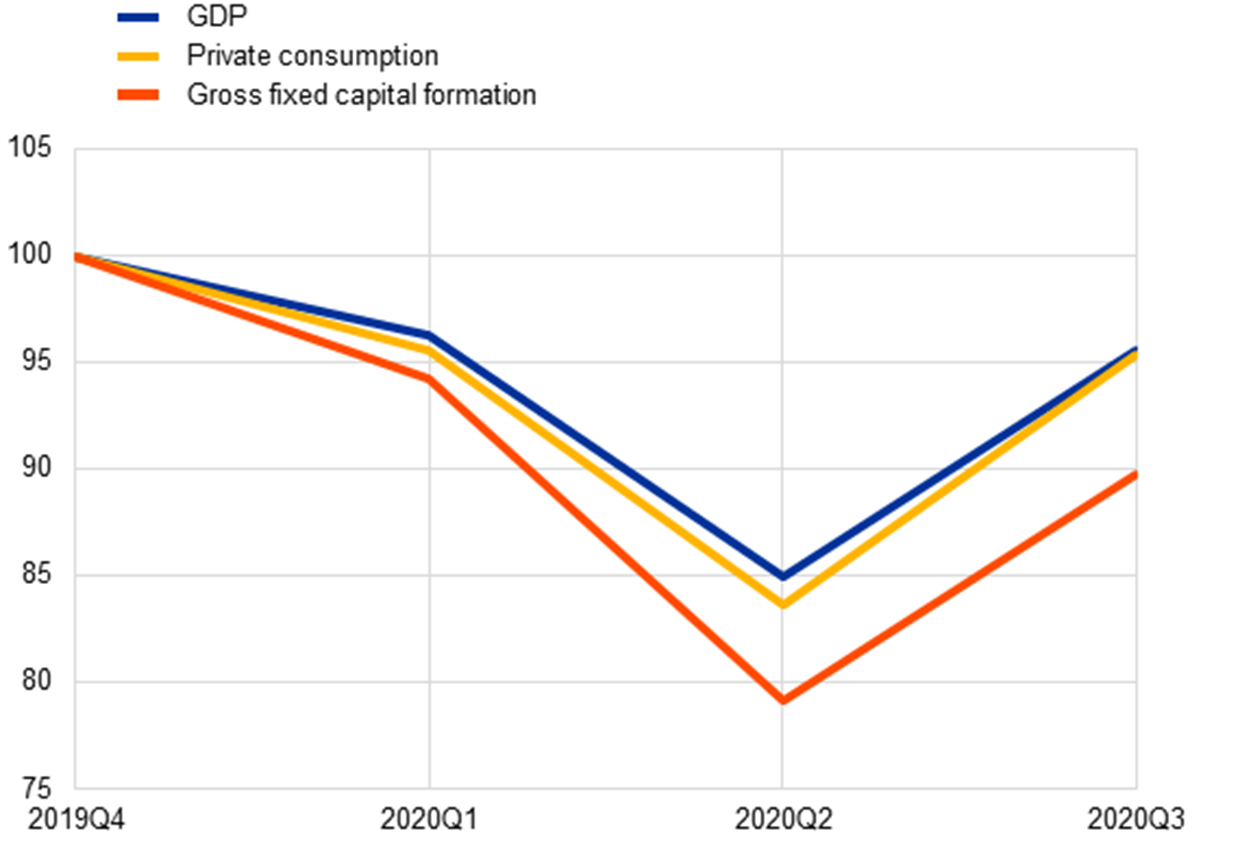

With high uncertainty compounding weak demand and financial vulnerability[3], it is not surprising that businesses today are reluctant to make irreversible decisions. According to a recent survey by the European Investment Bank, more than 80% of companies consider uncertainty the main barrier to investment – and this figure rises to 96% in Italy.[4] It is therefore little wonder that, at the end of the third quarter, total investment in the euro area was about 10% below its pre-pandemic level. Consumption and GDP were down 4.6% and 4.3%, respectively.

Chart 1 - Euro area business investment, private consumption and GDP

(index: Q4 2019 = 100)

Source: Eurostat.

So the question for policymakers is how to create certainty for businesses to invest once more.[5] We cannot provide clarity about when the vaccine will be widely available or even how people will respond when that day comes. But we can guarantee our commitment to support the recovery: the stabilisation effort should therefore continue until the economy is on a solid, durable recovery path.

Indeed, if firms are to invest more today, they must be confident that their financing costs will not rise prematurely and leave them with an unaffordable debt burden. For monetary policy, this means providing certainty about financing conditions well into the future.

Last week, the ECB’s Governing Council did just that.

The ECB’s contribution: preserving favourable financing conditions

Since the very beginning of this crisis, the ECB has taken forceful measures to ensure that all sectors can benefit from favourable financing conditions.

In March we launched the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), under which we had purchased €700 billion of private and public sector bonds by the end of November. Nearly all euro area sovereigns are now borrowing at negative rates up to five-year maturities, while corporate bond spreads have narrowed significantly.

Our purchases were complemented by a further easing of our targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). Over the past six months, more than €1.3 trillion has been allotted to banks at very favourable rates on the condition that they continue providing financial support to the real economy. TLTROs are a powerful form of support to small and medium-sized enterprises, which mainly rely on bank lending.

Our measures are ensuring that households, firms and governments can benefit from very accommodative financing conditions throughout the euro area. And in order to provide the certainty that the economy needs, the ECB is committed to preserving favourable financing conditions well into the future. To this end, last week we decided to strengthen our monetary policy action.

We increased the envelope of the PEPP by €500 billion, to a total of €1.85 trillion, and extended the horizon for the net purchases until at least March 2022.[6] This large envelope gives us considerable firepower. It allows us to respond flexibly at any time and with the necessary force to resist a premature tightening of financing conditions that could jeopardise the return of inflation in a sustained way to our aim of 2% over the medium term.

We have also extended the most favourable conditions on our TLTROs until June 2022 and broadened their size, in terms of maximum borrowing allowance. This will help calm fears of a tightening of financing conditions in the coming months – fears which we saw emerging in our latest survey on the access to finance of small and medium-sized enterprises.[7]

The PEPP envelope can be further expanded and extended, if warranted by the inflation outlook. And we stand ready to adjust all our instruments if downside risks to the outlook materialise, including those stemming from exchange rate dynamics. Indeed, an appreciation of the euro could significantly affect euro area inflation.[8]

There should be no doubt here: the ECB will not accept inflation settling at levels that are inconsistent with its aim. This is why we took action, and why we will continue to provide the monetary accommodation that is necessary to support the convergence of inflation to 2% over the medium term.

Our commitment to preserve favourable financing conditions will support the strengthening of inflation dynamics in two main ways.

First, over the coming months, where uncertainty is still high and the private sector is reluctant to take risks, fiscal policy will remain the main actor in the stabilisation effort and, as such, a key channel for transmitting monetary policy to the real economy.[9] Confidence in future financing conditions will remove obstacles to fiscal policy playing this role in full.

And when uncertainty recedes, monetary transmission through the private sector will gain more traction. Firms will be able to take full advantage of favourable financing conditions and carry out their investment plans. This is the second expansionary effect – and, crucially, the ECB’s commitment to preserve favourable financing conditions makes this effect more powerful over time.

That commitment is linked to supporting the return of inflation to our aim over the medium term. Given our projections – which foresee that even in a mild scenario inflation would rise to only 1.5% in 2023 – this means that financing conditions will need to remain very supportive even as growth accelerates from next year onwards. As a result, monetary policy will become more accommodative relative to the growth outlook.

Also in the light of the prolonged deviations of inflation below our aim over a number of years, a steady return to 2% is essential to anchor inflation expectations.

Investing in Europe’s recovery

But firms need certainty about more than just financing conditions. They also need reassurance about future demand and growth.

To lift the economy out of the crisis, governments need to wisely use the fiscal space created by our monetary policy and other key decisions at the European level – in particular joint EU borrowing. Next Generation EU (NGEU) alone will provide fiscal support amounting to about 5% of euro area GDP, focused in particular on those countries that have been hit hardest by the crisis, including Italy.

We will exit this crisis with higher public and private debt levels everywhere, so achieving growth rates that remain higher than interest rates will be crucial. For fiscal authorities, this means they should focus on high-quality, productive investment spending that lifts potential growth.

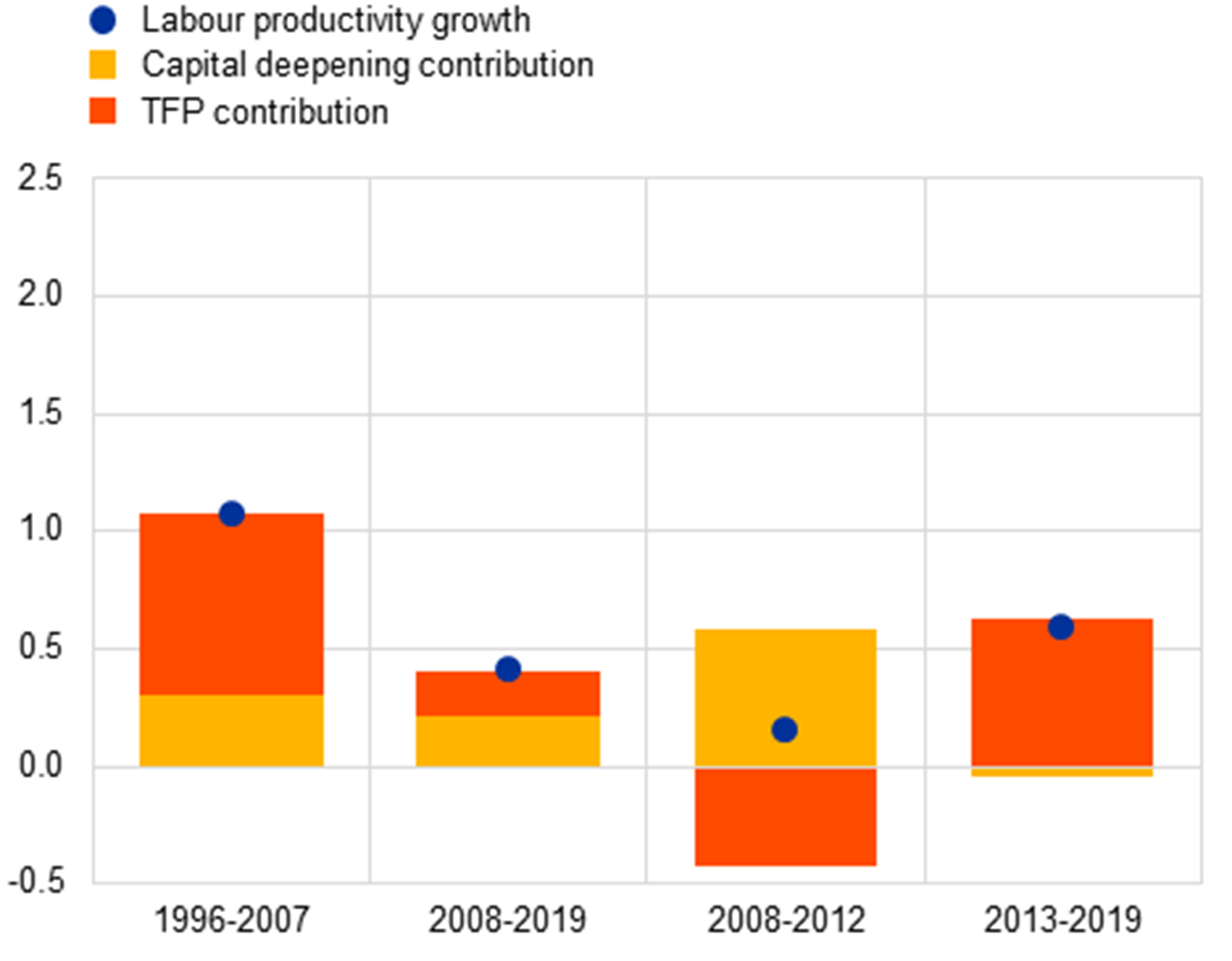

Many European economies have seen their growth capacity decline over recent decades. Capital deepening virtually stagnated, leading to lacklustre productivity performance.[10] Reversing this trend is necessary to ensure debt sustainability.[11]

Chart 2 – Labour productivity growth and decomposition

(period averages of annual percentage changes and percentage point contributions)

Sources: The European Commission’s AMECO database and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Productivity is measured in terms of output per person employed. Percentage point contributions are computed using a Cobb-Douglas production function, with capital deepening contributions estimated using two-period average factor shares. The total factor productivity (TFP) contribution is taken as the residual.

NGEU spending should focus on investment in those areas with the greatest potential to boost productivity and labour participation. If this happens, the possible gains are large. According to ECB estimates, NGEU funds could increase real output in the euro area by up to 1.5% by 2026 relative to the baseline scenario. High efficiency and institutional quality will be key to maximising the benefits of NGEU.

For Italy, the possible gains are larger: up to 3.5% of GDP if funds are well invested. Moreover, NGEU grants could reduce public debt-to-GDP ratio by more than 5 percentage points by 2026.[12]

The gains will be highest if investment spending is targeted at the technologies and sectors that will drive the economy after the pandemic.[13] More than half of EU firms expect to increase their use of digital technologies in response to COVID-19.[14] This requires enhancing digital skills and infrastructure, in order to be ready to face the digital challenge. For example, in the euro area the share of individuals with at least basic digital skills ranges from 79% in the Netherlands to 42% in Italy.[15]

If spent wisely, NGEU funds will contribute to significantly improving technological capabilities. This would not only ensure that all our economies are ready to take advantage of this transformation. It would also reduce one of the differences in structural conditions that has contributed to divergences among European economies.[16]

NGEU funds can be directly used to accelerate digitalisation, for instance by increasing the use of e-government services. The fiscal space that NGEU creates in national budgets can also be reallocated towards digital training and education.

In the past, pandemics have sparked innovation in how economies are structured. Recent research shows that government interventions during the 1918 influenza pandemic helped spur innovation after the pandemic ended.[17] I see no reason why we cannot do the same.

However, we must also recognise that digitalisation tends to reward those with higher skills and so could exacerbate inequalities. Therefore, during the transition attention should be given to the social implications of reallocating resources towards more digitalised sectors.[18]

Investment to support the transition to a low-carbon economy will also be a key component of the recovery from the pandemic throughout the euro area. Italy should not be lagging behind in this area.

Conclusion

The coronavirus shock may be a turning point for Europe. The agreements reached by EU leaders in recent months show that we all understand that addressing challenges together brings benefits to everyone.

Our common response at the European level must now continue, in order to provide clarity on the policies that will be implemented to underpin and strengthen the recovery.

To put the economy on a solid, durable growth path consistent with the return of inflation to our aim, monetary and fiscal policy need to remain accommodative for an extended period of time.

Fiscal policy must focus on investment in order to boost potential growth. We must resist the temptation to take hazardous shortcuts. Only growth, not financial alchemy, can guarantee debt sustainability and pave the way for prosperity.

- Lagarde, C. (2020), “Monetary policy in a pandemic emergency”, keynote speech at the ECB Forum on Central Banking, 11 November; and Panetta, F. (2020), “Asymmetric risks, asymmetric reaction: monetary policy in the pandemic”, speech at the meeting of the ECB Money Market Contact Group, 22 September.

- Panetta, F. (2020), “Why we all need a joint European fiscal response”, contribution published by Politico, 21 April.

- Results from the ECB’s Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE) show an increase in the number of firms considered vulnerable owing to a combination of lower profits and turnover, higher interest expenses and increasing debt-to-asset ratios. See ECB (2020), Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area – April to September 2020, 24 November.

- The annual EIB Group Survey on Investment and Investment Finance (EIBIS) gathers qualitative and quantitative information on investment activities by around 12,000 companies across the European Union.

- Reducing uncertainty is key to the effectiveness of the policy stimulus, as the responsiveness of firms to any given policy stimulus may be much weaker in periods of high uncertainty. See Bloom, N., Bond, S. and Van Reenen, J. (2007), “Uncertainty and Investment Dynamics”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 74, No 2, April, pp. 391-415.

- The Governing Council also decided to extend the reinvestments of the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP until at least the end of 2023.

- According to the latest SAFE round, SMEs were expecting a deterioration in the availability of most external financing sources in the next six months.

- The nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against 42 selected trading partners already appreciated by 5.9% in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared with the average level in the first quarter of 2020. This movement has significantly affected our inflation projections for 2021 and 2022.

- To avoid self-fulfilling liquidity traps, research suggests that monetary and fiscal policy should complement each other, allowing the fiscal authority’s response to changes in economic conditions to be sufficiently elastic so that government spending can be raised by the amount needed to offset the macroeconomic effects of the decline in private sector confidence. See Nakata, T. and Schmidt, S. (2019), “Expectations-driven liquidity traps: implications for monetary and fiscal policy”, Working Paper Series, No 2304, ECB; and Schmidt, S. (2017), “Fiscal Activism and the Zero Nominal Interest Rate Bound”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 49, No 4, pp. 695-732.

- ECB (2017), “The slowdown in euro area productivity in a global context”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3. This development is not limited to the euro area. Investment weakness has accounted for the lion’s share of the slowdown in productivity growth over the past decade in advanced economies. See Dieppe, A. (ed.) (2020), Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers and Policies, World Bank.

- Panetta, F. (2020), op. cit.

- The estimates mentioned in the text refer represent the upper bound of an ideal scenario where all resources are used to fund productive investment.

- Anderton, R. et al. (2020), “Virtually everywhere? Digitalisation and the euro area and EU economies”, Occasional Paper Series, No 244, ECB, June.

- European Investment Bank (2020), EIB Group Survey on Investment and Investment Finance.

- Eurostat (2020), Survey on ICT usage in households and by individuals.

- Gräbner, C., Heimberger, P., Kapeller, J. and Schütz, B. (2020), “Is the Eurozone disintegrating? Macroeconomic divergence, structural polarisation, trade and fragility”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 44, No 3, pp. 647-669.

- Berkes, E. et al (2020), “Lockdowns and Innovation: Evidence from the 1918 Flu Pandemic”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 28152, National Bureau of Economic Research, November.

- Basso, G. et al. (2020), “The new hazardous jobs and worker reallocation”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No 247.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts