Implications of Brexit for the EU financial landscape

Implications of Brexit for the EU financial landscape

Published as part of Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, March 2020.

Brexit will result in a substantial structural change to the EU’s financial architecture over the coming years. It could be particularly significant for derivatives clearing, investment banking activities and securities and derivatives trading as the reliance on service provision by UK financial firms is more pronounced in these areas and the provision of such services is currently linked to the EU passporting regime. At the same time, the precise overall impact of Brexit on the EU’s future financial architecture in general – and on these specific areas in particular – is difficult to predict at this stage, and may change over time.

This special feature makes a first attempt at analysing some of the factors that may affect the EU’s financial architecture post-Brexit. It focuses on areas which currently show strong reliance on the UK and are of particular relevance for the ECB under its various mandates.

One factor which may affect the future architecture is the extent to which regulatory and supervisory frameworks in the UK may diverge from EU ones, as alignment is a precondition for recognising the UK as an equivalent jurisdiction under the EU’s existing third-country regimes. If the provision of services out of London continues to be allowed, regulatory and supervisory consistency is paramount to limit the scope for regulatory arbitrage. Financial stability considerations will be a key factor in the forthcoming decisions around equivalence. The EU is prepared for all scenarios, including regulatory and supervisory divergence. In the light of the current uncertainty regarding the equivalence of the UK’s framework in the future, the private sector must also continue to prepare for all possible outcomes beyond 31 December 2020.

Economic incentives faced by market participants are another factor likely to affect the EU’s financial architecture. For activities subject to economies of scale, splitting EU and non-EU service provision may entail efficiency costs. This is particularly significant for the central clearing of derivatives, where restrictions on access to central counterparties (CCPs) based in the UK could reduce market depth and increase costs for clients, at least in the near-to-medium term. For activities subject to economies of scope or currently benefiting from agglomeration effects in London, the implications are less clear. Furthermore, current advantages in terms of efficiency need to be balanced against systemic risks that could arise from significant reliance on a third-country jurisdiction for key financial services.

For a number of banking activities, such as deposit-taking and lending, an EU equivalence regime does not exist and continued cross-border provision of services is not possible. Many UK-based banks are in the process of setting up or expanding their presence in the euro area. When their target operating models are achieved, these banks plan to move more than €1,200 billion of assets to their euro area entities.

Based on initial data on bank relocations, it would seem that relocations could concentrate in a few centres in the euro area, possibly reinforcing the multi-centricity of the EU financial system. Such a multi-centric financial system would reduce concentration risks. At the same time, without a high level of fluidity between the different financial centres, financial fragmentation may arise, at least temporarily.

In order to address this concern, fostering the integration of EU capital markets is a key priority for the capital markets union. To this purpose, EU financial hubs will need to build capacity and interact efficiently to ensure market functioning. This will require an increased level of supervisory convergence within the EU.

Brexit thus reinforces the rationale for policies aimed at better mobilising domestic savings into capital market activities, in particular in areas such as equity financing, private equity and venture capital, with a view to diversifying funding sources, supporting investment and enhancing private risk sharing. Overall, this would contribute to developing domestic capacity in areas where the EU currently relies heavily on the UK. In this regard, delivering on the capital markets union agenda will be key to renewing the EU’s ambition to develop genuine capital markets and cross-border financing of debt and equity instruments.

1 Introduction

Currently, the financial systems of the EU27 and UK are intertwined and deeply integrated. A number of key activities which serve EU27 clients are provided out of London, one of the most developed financial centres in the world. For some EU27 financial and non-financial firms, the City of London also represents a gateway to global financial markets.

Brexit will change the legal framework in which financial firms will operate in the future. The degree of integration between the EU27 and the UK will probably evolve over the coming years and will be driven by both regulatory and economic considerations. From a regulatory perspective, details of the future EU -UK relationship in financial services are still highly uncertain and remain subject to, in particular, the extent of regulatory alignment between the two jurisdictions going forward. This, in turn, will determine the manner in which the EU equivalence framework will be applied to the UK. Depending on these factors, some activities and sectors are likely to be affected more than others. As for other major third countries, the relationship with the UK in the area of financial services will depend on regulatory developments in both jurisdictions as well as the development of domestic EU capital markets (Section 4).

The future economic and financial relationship between the UK and the EU27 may also affect the structure, development and integration of the EU27 financial system. The EU27 will have to foster domestic capacity and develop markets in areas where it currently relies on the UK. Eventually, this would likely change the financial structure – understood as the mix of different financial markets and intermediaries – in the EU27 in a more fundamental way. Brexit could also affect the way in which the EU27 accesses global financial markets, i.e. its integration in the global financial system. Large-scale relocation from London could, over time, result in the emergence of a centralised landscape or multiple financial centres. To increase the effectiveness of financial markets in both scenarios, financial integration within the EU27 would need to be strengthened. These potential changes would also affect a number of the ECB’s key policy tasks, including the transmission of its monetary policy and its tasks in the area of financial stability.

This special feature assesses these implications of Brexit for the EU financial system in three parts. First, it makes a preliminary attempt to identify areas of the financial system most reliant on the UK, and links these with third-country regimes which will shape the provision of services from the UK after Brexit, provided the legal preconditions are met (Section 2). Section 3 examines possible drivers and implications of changes in cross-border conduct of activities, including a relocation of financial activities. Possible policy responses, particularly in the context of the European Capital Markets Union (CMU), are discussed in Section 4.

2 Euro area reliance on the UK for financial services and relevant regulatory frameworks

2.1 Euro area reliance on the UK for financial services

Changes to the euro area financial landscape following Brexit are likely to be concentrated on activities where the euro area currently relies on the UK the most. The importance of London to the euro area financial system varies substantially across financial activities. For example, derivatives clearing and investment banking activities are reliant on the UK to a significant extent, while UK-domiciled banks have a generally limited role in direct lending to the euro area real economy.

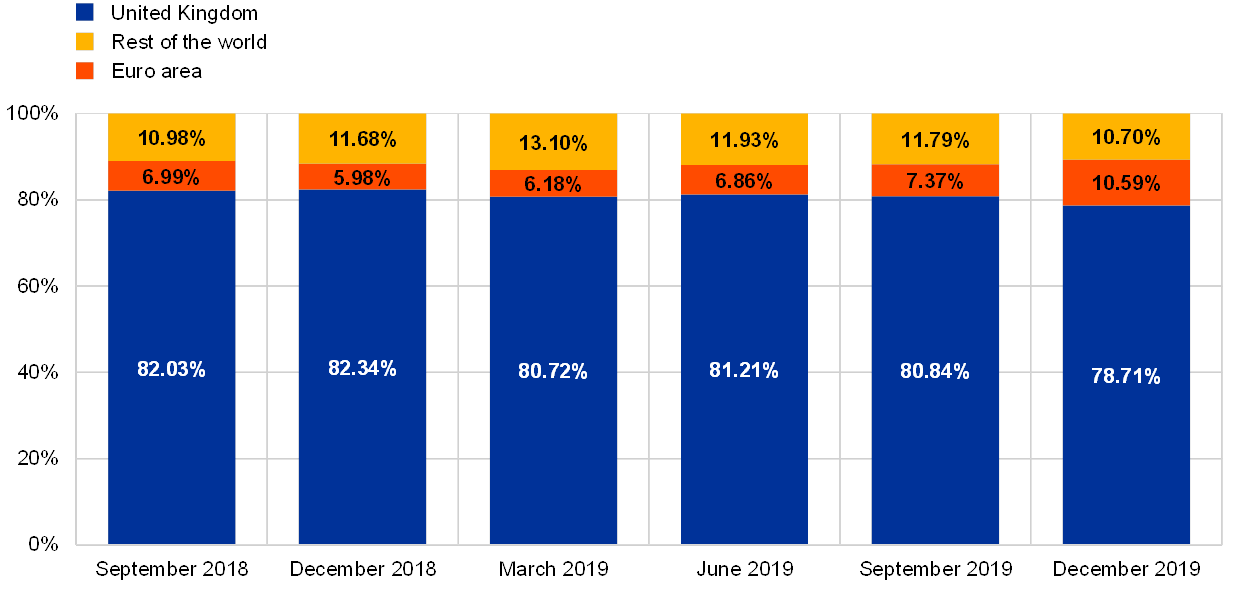

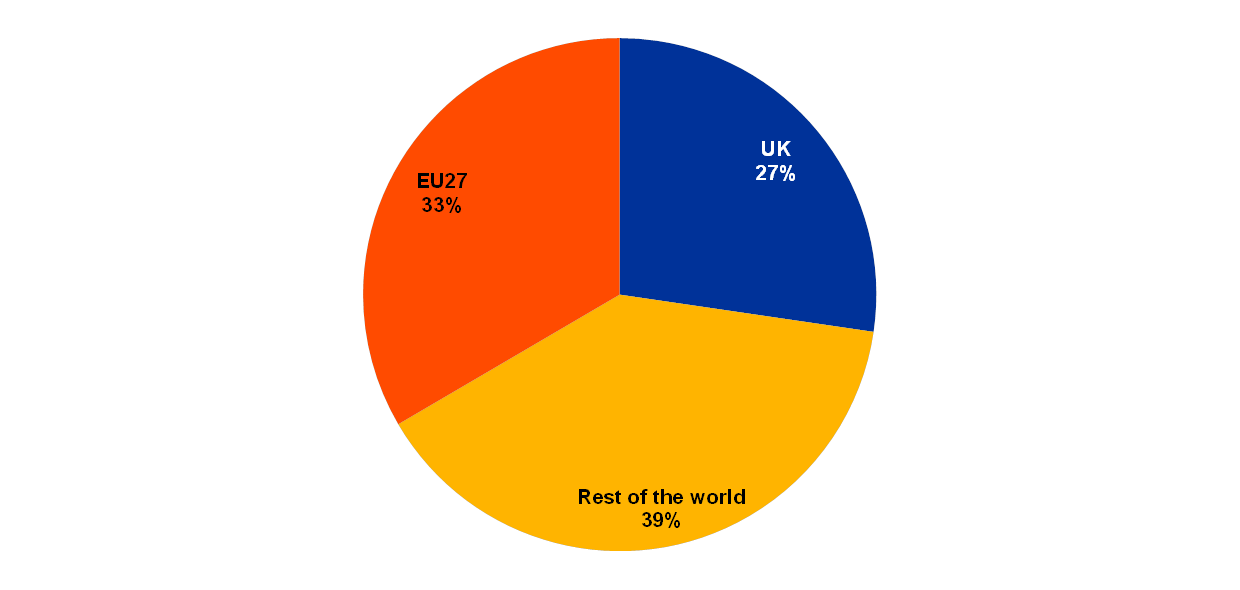

Reliance is very pronounced in derivatives clearing. As at December 2019, almost 80 per cent of all euro area clearing members’ OTC derivatives positions were cleared through UK CCPs (Chart A.1). Large investment banks operating out of London also play a significant role in euro area bilateral OTC derivatives markets. As at August 2019, over a quarter of uncleared OTC derivatives held by euro area counterparties were sourced from the UK (Chart A.2). While issues related to uncleared OTC derivatives are unlikely to create financial stability risks in a no-deal scenario, the activities of some of these institutions are still relevant to the provision of liquidity to euro area markets over the longer term.[1] Large investment banks are in the process of implementing contingency plans with a view to continuing to service EU clients.

Outstanding cleared OTC derivatives transactions of euro area clearing members

Source: ECB EMIR data.Note: Data from two trade repositories have been excluded owing to limited availability and quality.

Geographic breakdown of counterparties to euro area uncleared OTC derivative contracts

Source: ECB estimates on EMIR data.Notes: Shares based on mid-point of upper and lower bound estimates. Under the EMIR reporting regime, there is an obligation for both counterparties to a derivative contract to report the trade (“double-sided reporting”). Due to misreporting and underreporting, not all trades can be matched, i.e. there are unpaired trades. The assumption that all unpaired trades are the result of underreporting leads to an “upper bound” estimate of the uncleared derivatives exposures. Conversely, the assumption that all unpaired trades are the result of misreporting leads to a “lower bound” estimate. Data as at 29 August 2019.

Global investment banks operating out of the UK are also key providers of financial services to euro area non-financial firms. Many global investment banks currently access the euro area market from London. They support access of euro area non-financial corporations to capital markets and provide a number of services. For instance, global banks play a very active role in debt and equity issuance (Charts A.3 and A.4), as well as mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and syndicated loans (Charts A.5 and A.6).

Euro area non-financial corporations’ debt issuance via non-euro area-owned banks

(left-hand scale: number of deals; right-hand scale: percentage shares)

Source: Dealogic.Notes: Banks involved in deals as manager, co-manager, bookrunner, participant or underwriter are categorised as “euro area” or “global”, depending on the location of the parent. Prior to Brexit, global banks typically accessed the market from London. Bars reflect the total number of deals individual banks participated in. As many banks typically participate in a single deal, this may entail double-counting of deals in total left-hand side axis figures. The red line is the ratio between the blue and yellow bars and can be taken as a proxy for the relevance of global banks to the euro area market.

Euro area non-financial corporations’ equity issuance via non-euro area-owned banks

(left-hand scale: number of deals; right-hand scale: percentage shares)

Source: Dealogic.Notes: Banks involved in deals as manager, co-manager, bookrunner, participant or underwriter are categorised as “euro area” or “global”, depending on the location of the parent. Prior to Brexit, global banks typically accessed the market from London. Bars reflect the total number of deals individual banks participated in. As many banks typically participate in a single deal, this may entail double-counting of deals in total left-hand side axis figures. The red line is the ratio between the blue and yellow bars and can be taken as a proxy for the relevance of global banks to the euro area market.

M&A deals involving euro area non-financial corporations financed by non-euro area-owned banks

Source: Dealogic.Notes: Banks involved in deals as lead bank are categorised as “euro area” or “global”, depending on the location of the parent. Prior to Brexit, global banks typically accessed the market from London. Bars reflect the total number of deals individual banks participated in. As many banks typically participate in a single deal, this may entail double-counting of deals in total left-hand side axis figures. The red line is the ratio between the blue and yellow bars and can be taken as a proxy for the relevance of global banks to the euro area market. The sample includes transactions in which the acquirer, the target or both are firms based in the euro area and pertain to any non-financial and non-government sector.

Syndicated loans to euro area non-financial corporations led by non-euro area-owned banks

Source: Dealogic.Notes: Banks involved in deals as lead bank are categorised as “euro area” or “global”, depending on the location of the parent. Prior to Brexit, global banks typically accessed the market from London. Bars reflect the total number of deals individual banks participated in. As many banks typically participate in a single deal, this may entail double-counting of deals in total left-hand side axis figures. The red line is the ratio between the blue and yellow bars can be taken as a proxy for the relevance of global banks to the euro area market.

So far, evidence of relocation has been mixed across sectors. While some uptake can be seen in Chart A.1, overall relocation of derivatives clearing has been limited (see Box 1). Global banks currently serving the euro area out of London have completed authorisation procedures to establish or expand their presence within the EU27, ensuring that they can continue to serve this market after the UK has left the EU. Plans agreed with supervisors indicate that these banks aim to transfer over €1 trillion in assets in a scenario where the UK would not be granted market access under EU equivalence regimes and cross-border provision of services would be limited to existing national third-country regimes (Section 2.2 and Box 2).

2.2 Third-country frameworks for market access

While the parameters of the future EU -UK financial services regime are likely to evolve over time, some services might continue being provided directly from the UK via third-country regimes after Brexit. UK-based financial firms currently rely on passporting rights to provide services across the EU Single Market based on a single authorisation in their home Member State. UK-based firms will be subject to third-country regimes in EU financial services legislation following Brexit (Table A.1). Member States may further grant access to domestic markets for specific activities under national legislation. The EU has the option to recognise that the regulatory or supervisory regime of a third country is equivalent to the corresponding EU regime. For example, Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation[2] and Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II[3] (MiFIR/MiFID II), European Market Infrastructure Regulation[4] (EMIR) and Central Securities Depositories Regulation[5] (CSDR) allow investment firms, recognised central counterparties and central securities depositories from equivalent third countries to provide services to EU counterparties and markets, subject to a positive equivalence decision by the European Commission. But, while equivalence regimes exist in a number of areas[6], they do not replicate the passporting regime in the EU Single Market which allows EU-wide free movement of products and services based on a single rulebook and a common supervisory architecture.

The degree to which the UK will be able to benefit from market access under EU equivalence regimes will be decided unilaterally by the EU and it will be conditional on future regulatory choices in both jurisdictions. Indeed, the decision to grant the UK market access under different EU equivalence regimes will crucially depend on the degree of future regulatory alignment between EU and UK frameworks. It will also depend on risk management considerations associated with cross-border activity in terms of impact on EU financial stability, market integrity, investor protection and the level playing field in the EU internal market. Although the UK applied the EU’s regulatory framework prior to its departure, decisions on equivalence take into account potential risks to the EU on a forward-looking basis, as explained in the European Commission’s 2019 communication on equivalence.[7] The modalities of equivalence assessments and decisions are within the remit of the European Commission. From a risk perspective, both current regulatory and supervisory frameworks and intentions as to future changes appear relevant. And in the light of the current uncertainty regarding the equivalence of the UK’s framework in the future, the private sector must continue to prepare for all possible outcomes beyond 31 December 2020 – indeed, EU authorities have been calling for adequate preparations by the private sector throughout the Brexit process. The EU is prepared for all scenarios, with the previous considerations on Brexit-related risks continuing to apply.[8]

Even if equivalence is granted to the UK in some areas, the dynamic nature of regulatory and supervisory frameworks will require regular monitoring of these decisions. Initial equivalence determinations may become outdated as UK regulation evolves and diverges from EU regulation, potentially bringing risk to the EU’s financial system. In particular, the Commission will monitor whether equivalence decisions continue to fulfil the EU objectives for which they were taken. In doing so, it will also take into account changes in the regulatory framework of the third country, and whether the services and activities covered by the decision continue to respect the integrity of the EU internal market and preserve the level playing field vis-à-vis the UK and within the EU. Withdrawing an equivalence decision is a unilateral prerogative of the European Commission.

Mapping UK-reliant activities onto relevant third-country frameworks

Where provision of financial services directly from the UK is prohibited for regulatory reasons, these services would need to be provided by entities within the EU. The provision of services to EU clients by financial firms currently established in London will be determined by the extent of relocation and changes in the provision of services by existing EU-domiciled peers. A number of factors which may drive relocation of activities are discussed in the next section. Where UK entities are allowed to continue providing services under the EU’s third-country frameworks, there might be limited change to the current situation. Furthermore, in a number of areas, the City of London acts as a hub for global financial flows, rather than as an intermediary for intra-EU activities.

3 The structure of the post-Brexit euro area financial system

The nature of required changes and the post-Brexit structure of the euro area financial system will be affected dynamically by regulatory and economic factors. The different drivers are likely to vary substantially across business models as illustrated below for selected market segments such as central clearing and investment banking. Brexit is therefore likely to have heterogeneous effects on different types of financial firms, activities and sectors over time. Individual choices of firms will also matter, depending, for instance, on market opportunities. Over the medium term, policies fostering the attractiveness of EU capital markets globally could enhance incentives for providing services from within the EU (see Section 4). This section seeks to provide an assessment of the dynamics potentially affecting certain key sectors – although an exhaustive picture cannot be provided at this stage.

Economies of scale and market efficiencies from concentration dominate the central clearing business. At least in the near-to-medium term, restricting market access to UK CCPs could lead to lower market depth and increase costs in EU OTC derivatives markets, especially for end users (see Box A.1). If UK CCPs were not recognised, EU clients would in most cases need to switch to EU27 or recognised third-country CCPs, which may need to scale up their activity in some markets. UK CCPs would likely remain global clearing hubs for most services and have so far given no indication of further plans to relocate activities to the EU. The lack of access to global liquidity pools could negatively affect the competitiveness of EU dealer banks and increase costs for clients in certain products. However, given the EU’s significant reliance on UK systemic clearing activities, the EU will need to prioritise mitigation of any associated financial stability risks by ensuring ongoing regulatory alignment and effective EU supervisory oversight of these activities, as laid down in EMIR 2.

Box A.1 Central clearing: market concentration or fragmentation?

UK CCPs are leading global clearing hubs for a number of markets, including major OTC derivatives segments, including interest rate swaps (IRS) and credit default swaps, as well as other important markets such as futures on benchmark rates, commodities and repo markets. While there are many CCPs of different sizes and activities, a given market segment is typically cleared mostly in one or a very small number of CCPs. The drivers of market concentration include efficiencies gained through higher market liquidity and netting benefits[9], the existence of silos between trading venues and clearing houses, and the high sunk cost of developing new clearing services. As a result, although small CCPs may have a local footprint, cleared markets are structured around global hubs with broad cross-border access. For instance, LCH Ltd in London clears nearly 90% of all IRS cleared globally (in 26 different currencies).[10] The EU27’s reliance on these London clearing hubs is part of a global pattern.

So far, the main relocation operation from the UK to the euro area in terms of clearing has fostered further market efficiencies. In February 2019, a concerted effort between repo dealers and the two LCH CCPs in London and Paris (both owned by the London Stock Exchange Group) led to the relocation of the near-totality of euro-denominated repo clearing from the UK to France. In the eight months following this relocation, the average monthly value of cleared repo trades at LCH SA (Paris) increased to €15.1 trillion from €8.3 trillion in 2018, while at LCH Ltd it dropped from €8.1 trillion to €3.2 trillion (see Chart A), around 90% of which being repos on sterling-denominated gilts.[11] Euro-denominated repos are now cleared almost exclusively at euro area CCPs (largely at LCH SA)[12], enabling additional market efficiencies including balance sheet netting and access to TARGET2 -Securities.

Chart A

Repos cleared at LCH Ltd and LCH SA (monthly nominal amount)

(EUR billions, 2018 -2019)

Source: LCH.

Depending on market conditions which evolve over time, restrictions on cross-border access can create an economically inefficient discrepancy in swap pricing due to imperfect arbitrage between CCPs clearing the same instrument (CCP basis). Supply-demand imbalances and higher balance sheet costs of clearing eventually increase costs for banks that cannot use arbitrage between CCPs.

However, competition can also have positive effects, such as fostering innovation and exerting downward pressure on fees. Market concentration does not prevent competition in central clearing, provided that it is supported by dealer banks. The growth of euro IRS clearing at Eurex Clearing (Frankfurt), which has reached €14.1 trillion in notional outstanding (compared with €84.1 trillion at LCH Ltd), is a recent example. Competition between CCPs may also reduce concentration risk and a market with multiple CCPs can bring positive effects to financial stability by reducing systemic risk.

The breadth of cross-border activity and reliance on global markets are reflected in regulatory frameworks, which largely allow cross-border access. Under EMIR (the European Market Infrastructure Regulation, which established the EU regulatory framework for CCPs), the EU has granted recognition to 32 CCPs in 15 jurisdictions designated as equivalent, and other jurisdictions similarly allow the cross-border provision of clearing services: LCH Ltd is registered under the regulatory framework of eight jurisdictions in addition to the EU.

UK CCPs clear key markets in EU currencies, in particular the euro. Given the systemic importance of these activities for the EU, it is essential from an EU perspective to ensure that financial stability risks are adequately managed and to protect the rights and the stability of EU financial institutions which participate in UK CCPs. This means that the risks of regulatory divergence and a loss of EU supervisory oversight would be particularly pronounced in this area. UK CCPs must continue to comply with the EU’s high prudential, governance and operational standards and EU authorities must have the same degree of oversight over systemically important UK CCPs as over EU CCPs. EU legislators have pre-emptively addressed this issue with the adoption of EMIR 2, which amends EMIR to enhance the EU framework for the supervision of third-country CCPs. Under the new regulation, third-country CCPs which are systemically important for the EU will need to meet additional conditions for recognition. The potential for regulatory arbitrage can be mitigated by the direct application of EMIR standards to systemically important CCPs and the lack of oversight by EU authorities can be addressed with the involvement of ESMA and EU central banks. The new framework should therefore be expected to address the main regulatory issues raised by reliance on critical third-country infrastructures. EMIR 2 also addresses the case of third-country CCPs (or clearing services) having such substantially systemic importance to the EU that these mitigants prove insufficient to ensure regulatory alignment and supervisory cooperation. In this case, EMIR 2 envisages that these clearing services may be denied recognition to address outstanding risks.

Some UK-based banks are planning to transfer some activities from the UK to continue servicing the euro area (see Box A.2). These are largely global banks that act as intermediaries in capital and derivatives markets (see Box A.3) and provide financial services to euro area non-financial companies and governments. Banks may continue providing these services by establishing or expanding their presence in the euro area. These institutions are expected to be capable of managing all material risks potentially affecting them independently and at the local level. Their governance and risk management mechanisms will need to be commensurate with the nature, scale and complexity of the business, including adequate staffing of their euro area entities.

Box A.2 Bank relocation plans

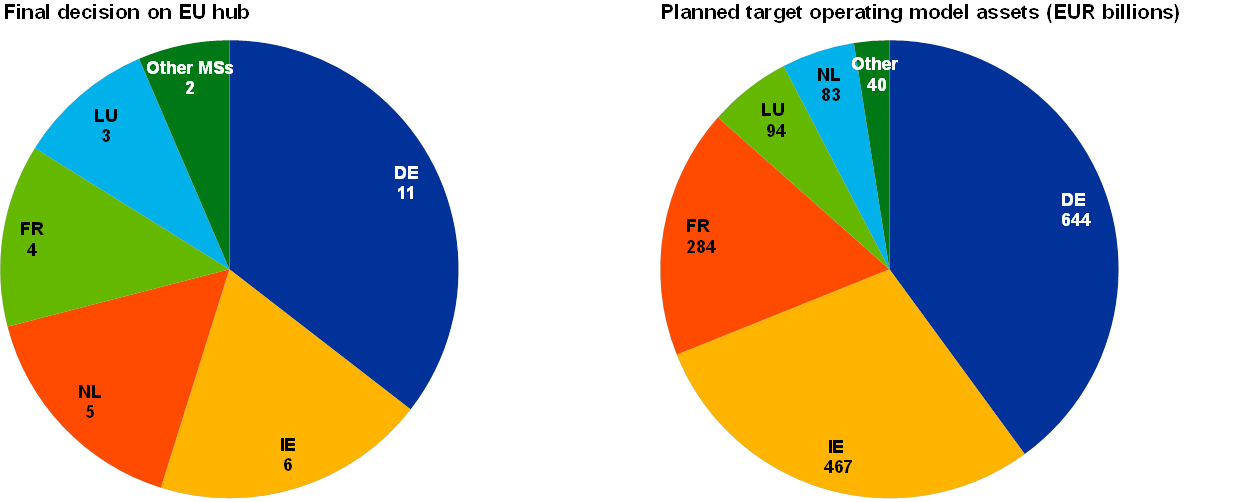

This box provides an overview of the relocation of activities so far and banks’ stated intentions regarding relocation. The information currently available indicates that activities could move to a number of countries within the EU27, as opposed to concentrating in a single location. However, this may change over time in response to banks’ choices and incentives.

Driven by the loss of passporting rights and the need to operate inside the EU to keep servicing EU clients, incoming institutions can pursue three main different relocation options: (i) setting up a new subsidiary/subsidiaries; (ii) setting up new branches; (iii) expanding existing subsidiaries/branches. As part of their Brexit strategy, large globally active banks are, in many cases, using a combination of these three options. A number of groups are also reorganising their network of European Economic Area branches, for example by re-attaching current branches of UK entities to their new EU hub. Some incoming banks are also planning to rely on national legislation in some EU Member States that allows the direct provision of certain services on a cross-border basis by third-country firms. Investment firms currently headquartered in the UK are also relocating parts of their activities to the EU27.

In their adverse Brexit-related scenarios, incoming credit institutions are planning to operate with more than €1,600 billion[13] in assets on the balance sheet of the group entities established in the euro area once they reach their target operating model. This would constitute an increase of more than €1,200 billion (or more than 300%) as compared with the end of 2017. This planned relocation of assets supports the expectation that incoming credit institutions will substantially increase their footprint in the euro area, with a view to avoiding disruptions in servicing their euro area clients after Brexit.

Around 25 Brexit-related formal authorisation procedures related to the establishment of new credit institutions or the restructuring of existing ones have been launched in the euro area. In addition, ten existing credit institutions are substantially increasing their activities due to Brexit. Most incoming institutions have indicated that their new main location in the EU will be Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and France (Chart A).

Chart A

Most incoming banks have indicated that their new main location in the EU will be Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and France

Sources: ECB supervisory information, ECB calculation.

Incoming banks with material capital market activities are planning to operate with a total of €837billion in capital market assets. Capital market business refers to sales, trading and treasury activities, excluding advisory or pure lending components. Interest rate products make up the largest asset class, accounting for 58.4% of the total, followed by equity (10.3%), credit (4.7%) and FX products (4.4%).[14] Other capital markets business (for example commodities) accounts for the remaining 22.2% (Chart B).

Chart B

Incoming banks with material capital markets activities

(percentages)

Sources: ECB supervisory information, ECB calculation.

Economies of scale and scope may create complex incentives regarding the relocation of various activities. Economies of scale seem to be present in banks that are more involved in investment banking activities, such as market-making. In this sense, splitting the provision of services to EU and non-EU clients may increase costs. Much of the literature on economies of scope in banking focuses on synergies between the provision of investment banking activities and more traditional activities. It includes spreading fixed costs, information economies, risk reduction and customer cost economies.[15] Benefits of scope could also exist in investment banking activities. For example, there may be synergies between providing brokerage and investment services or spot and derivatives trading for the same asset class. Incentives to relocate may be affected by the degree and scope of these synergies.

Economies of scale are present in euro area derivatives markets, while economies of scope across business lines seem more limited. According to granular information on euro derivatives, the list of most active dealers varies substantially across different asset classes and contract types. More specifically, different dealers are dominant in different asset classes. Even within asset classes, dealers tend to specialise in specific contract types, e.g. swaps, options and futures. In September 2019, the Herfindahl concentration index within asset classes and across contract types was below 15 per cent, a relatively low level. This evidence suggests that economies of scope in making derivatives markets are quite limited.

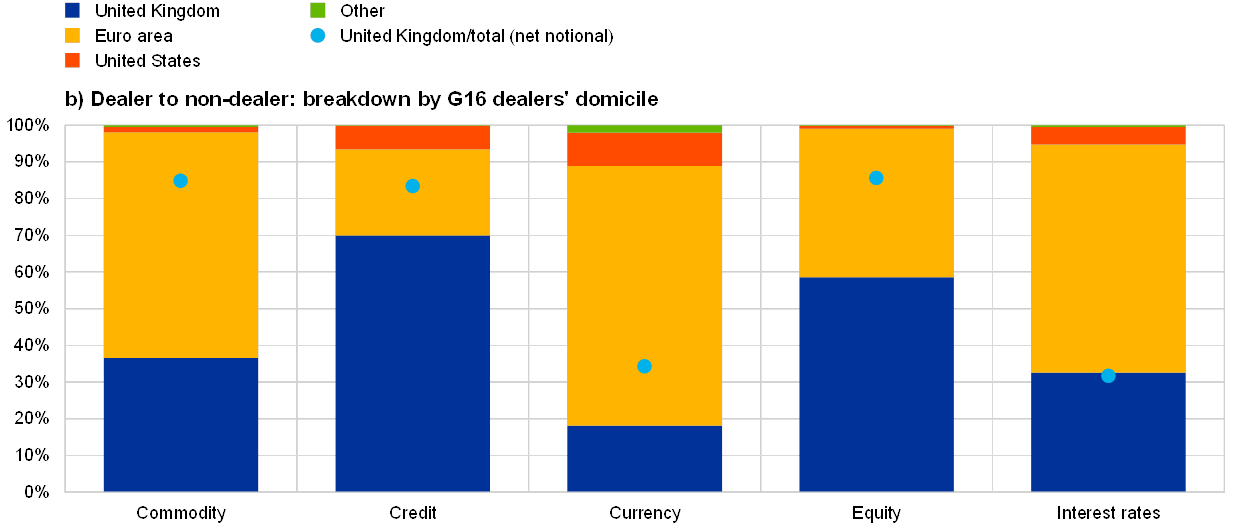

Box A.3 The role of UK-based dealers in the euro area derivatives market

Global dealers are pivotal players in trading euro area derivatives. Dealers provide liquidity and enhance price discovery in typically less transparent markets, such as OTC derivatives markets. This role is usually served by G16 dealers.[16] This box uses EMIR data to examine the role of G16 dealers in the euro area OTC markets. As at September 2019, the gross notional share of outstanding positions where at least one G16 dealer was involved ranged between 42% and 70% of the total across different asset classes (see Chart A, panel (a)). G16 dealers provide liquidity to other sectors, as captured by the yellow bars in the same chart. The role of G16 dealers is more pronounced in less liquid markets such as credit derivatives, where the share of derivatives traded OTC is larger (see the dots in Chart A, panel (a)).

Many G16 dealers currently serve the euro area market out of London. In this context, the liquidity provision of UK-based dealers is quite heterogeneous across asset classes (Chart A, panel (b)).[17] In gross notional terms, UK-based dealers are prominent in credit derivatives, which is a smaller market, while their role in interest rate derivatives is more limited. Compared with euro area dealers, they tend to take larger net exposures, especially for commodity, credit and equity derivatives (net notional, see dots in Chart A, panel (b)).[18] Since dealers typically do not take substantial and persistent net exposures, this could indicate that UK dealers may be offsetting the large net exposures they hold vis-à-vis euro area counterparties with other global dealers. This may reflect the role of UK-based dealers as intermediaries between the euro area and the rest of the world.

Chart A

Market breakdown by cluster of trades

Sources: EMIR data and ECB calculations. The analysis is carried out based on outstanding positions as at Q3 2019 and includes trades cleared to CCP via clearing members. According to Commission Delegated Regulation 151/2013, European (euro area or national) authorities have access to trades where at least one counterparty is resident in the EU (euro area or specific country), to trades where the reference entity is resident in the EU (euro area or specific country) and to trades where the underlying instrument is sovereign debt of a European (euro area or specific) country.Notes: Panel (a): the chart reports the gross notional traded as at September 2019 with a breakdown by asset class and segments (y-axis: left-hand side in trillion, right-hand side in percentages; x-axis: breakdown by asset classes). We distinguish three segments: “Interdealer” refers to trades where both counterparties are G16 dealers, “Dealers to non-dealers” refers to trades where one of the two counterparties of the trade is a G16 dealer and the other belongs to other sectors, “W/o dealers” refers to trades occurring between non-G16 dealer counterparties (e.g. CCP, investment funds, insurance companies, non-G16 banks, pension funds, non-financial corporations and other financial institutions). Panel (b): the chart reports the breakdown by asset class and G16 dealers’ domicile as share of gross notional traded as at September 2019, dots indicate UK-domiciled dealers as share of net notional (y-axis: in percentages; x-axis: breakdown by asset classes).

UK-based dealers are important in the euro area credit default swap (CDS) market. UK dealers play a prominent role in providing liquidity in the CDS market to a number of euro area sectors, most notably banks. This is captured by the ratio of net over gross exposures and expressed by the thickness of the edges in panel (a) of Chart B.[19] Meanwhile euro area G16 dealers dominate the euro interest rate swap (IRS) market, with strong directional exposures towards non-financial firms and investment funds. In both markets, UK-based and euro area dealers are highly interconnected.

Chart B

Market breakdown by cluster of trades

a) Credit default swap

b) Interest rate swap

Sources: EMIR data and ECB calculations. The analysis is carried out based on outstanding positions as at Q3 2019 and includes trades cleared to CCP via clearing members. According to Commission Delegated Regulation 151/2013, European (euro area or national) authorities have access to trades where at least one counterparty is resident in the EU (euro area or specific country), to trades where the reference entity is resident in the EU (euro area or specific country) and to trades where the underlying instrument is sovereign debt of a European (euro area or specific) country.Notes: The size of each node reflects the gross notional traded by each sector. Light blue nodes represent euro area non-dealer sectors. G16 dealers are aggregated by country of domicile in euro area (EA), UK and other countries (RoW). The thickness of each link reflects net/gross notional traded between the two groups of counterparties. In the centre of both networks, dealers interact with each other in the interdealer market, while the outer circle shows their liquidity provisioning role towards other sectors. NFC stands for non-financial corporations, CCP for central clearing counterparties, ICPF for insurance companies and pension funds, BANK for commercial and investment banks other than G16, IF for investment funds and Other is a residual category including GOVT (governments), OFI (other financial institutions), NCB (national central banks) and MMMF (money market mutual funds).

Brexit could affect the geography of financial centres in Europe more broadly. The literature on financial centres often cites “ecosystem effects”, whereby financial firms benefit from close geographic proximity to other institutions providing similar and complementary services. Such benefits may arise, for example, due to access to specialised labour pools, with the availability of outside employment opportunities also encouraging a further concentration of human capital in one location. On the other hand, benefits arising from proximity to the client base could incentivise a more even spread of activity across the euro area. Kindleberger (1973 and 1974) argues that financial centres develop through a combination of market efficiency – arising from scale, market depth, access to information and proximity to economic activity – and institutional or socio-political factors. Subsequent work has highlighted the benefits of placing international market infrastructure and banking in a single location but also the role of information sensitivity in driving geographic distribution.[20]

This complex mix of incentives will eventually be reflected in the emerging structure of the euro area financial system. According to preliminary evidence on the relocation plans of banks, a small number of “hubs” and some degree of activity concentration could emerge (see also Box A.2). Based on market intelligence, this pattern also seems to be confirmed for relocation activities beyond banking. A sizeable fraction of asset management firms and insurance companies affected by Brexit are planning to move to Ireland and Luxemburg or have already done so. The Netherlands, meanwhile, is mainly attracting firms such as trading platforms, exchanges and fintechs. If these dynamics are confirmed, and the multi-centric structure of the euro area financial system becomes more pronounced, it will be crucial to implement policies that foster an efficient interaction between different hubs (see Section 4). Such a multi-centric financial system would reduce concentration risks.

4 Implications for the capital markets union

Brexit reinforces the need to complete the capital markets union (CMU).[21] The CMU aims to develop new sources of funding for companies, remove barriers between EU capital markets and broaden the role of the non-bank sector. The CMU would improve the capital channel for cross-border risk sharing and complement the credit channel of the banking union (BU).[22] Fostering equity financing is one of the objectives of the CMU. It could support investment and private risk sharing, and appears better suited for financing young innovative companies at an early stage and funding the transition to a low-carbon economy (see Box A.1 in the first chapter). The CMU therefore provides a policy agenda to tackle challenges related to market fragmentation and the potential reduction in market depth and efficiency resulting from Brexit. It can also enhance the attractiveness of EU’s capital markets more broadly on the global stage.

Measures aimed at developing capital markets in the EU would help to ensure strengthened domestic capacity in areas where the EU financial system currently strongly relies on London. For instance, after Brexit, the EU could lose access to a significant market for equity capital. The CMU provides a policy agenda for developing domestic capacity in the area of equity financing, private equity and venture capital. Redoubling efforts to foster CMU initiatives aimed at developing genuine capital markets and cross-border financing of both debt and equity instruments (as has been undertaken with the securitisation and venture capital regulations) seems all the more warranted in a post-Brexit world.

Policies fostering the integration of EU capital markets would help ensure efficient interaction of EU financial hubs. If the multi-centricity of the EU financial system were to become more pronounced post-Brexit, the efficient interaction of different EU financial hubs would become even more important to supporting effective market functioning. Currently, barriers to the cross-border provision of services, such as differences in national insolvency and taxation regimes, prevent integration in the euro area. While legislation passed in the aftermath of the crisis provided a first step towards a single rulebook for capital markets in the EU, such markets remain subject to national rules and supervision.[23] This may also open the door to regulatory arbitrage. A large-scale increase in euro area capital market activities would reinforce the case for more centralised oversight and supervision of markets.[24] In this context, it is also important to strengthen the risk identification and surveillance framework and the macroprudential toolkit for the non-bank financial sector.[25]

For services that could continue to be provided out of London based on third-country access regimes, regulatory and supervisory consistency is paramount to limit the scope for regulatory arbitrage and risks to financial stability. In the absence of a unified EU-level framework, a patchwork of national frameworks for the cross-border provision of services could give rise to regulatory arbitrage, as firms could circumvent host supervision and EU regulatory requirements. The details of the future cooperation between the EU and the UK and the degree of regulatory alignment over time will determine the level of interaction between the two financial systems. This, in turn, will frame the scope for the continued cross-border provision of services by UK financial entities. Appropriate oversight and toolkits available to EU regulators and supervisors will therefore be necessary to contain risks to financial stability in the euro area, especially considering that existing third-country regimes were not developed to manage a substantial degree of cross-border provision of services to EU entities. Building a unified EU-level framework or increasing harmonisation of national third-country regimes will be necessary to enhance the EU’s supervisory framework within the banking union. For instance, the authorisation and supervision of third-country branches should be further harmonised at the EU level.

While Brexit could strengthen the rationale for developing and integrating EU capital markets, the relevance of the CMU agenda goes beyond Brexit. Progress on the CMU project is crucial to enabling EU capital markets to meet the financing needs of European companies which at the moment are mostly met in London. At the same time, the preliminary insights highlighted in this special feature suggest that post-Brexit relocation dynamics are difficult to predict and depend on complex drivers and incentives. Therefore, a policy agenda seeking to increase the depth and efficiency of EU financial markets will need to look beyond Brexit and enhance the attractiveness of the EU’s capital markets on the global stage.

5 References

Beccalli, Elena, Anolli, Mario and Borello, Giuliana (2015), "Are European banks too big? Evidence on economies of scale", Journal of Banking & Finance, 58, pp. 232 -246.

Berger, Allen N., Hanweck, Gerald A. and Humphrey, David B. (1987), "Competitive viability in banking: Scale, scope, and product mix economies", Journal of monetary economics, 20.3, pp. 501 -520.

Duffie, D. et al. (2015), "Central Clearing and Collateral Demand", Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 116, pp. 237 -256.

de Guindos, Luis (2019), “Opportunities and challenges for the euro area financial sector”, Opening speech at the 22nd Euro Finance Week, Frankfurt am Main, 18 November.

de Guindos, Luis (2020), “Europe’s role in the global financial system”, Speech at the SUERF/De Nederlandsche Bank conference, Amsterdam, 8 January.

Kindleberger, C. (1973), “The formation of financial centres: A study in comparative economic history”, Department of Economics Working Paper, No. 114, MA: MIT Cambridge, August, pp. 1 -115.

Kindleberger, Charles (1974), “The Formation of Financial Centers: A Study in Comparative Economic History”, Princeton Studies in International Finance, No. 36, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

European Central Bank (2016), “Special Feature A: Financial integration and risk sharing in a monetary union”, Financial Integration Report.

European Central Bank (2019a), Box 1 entitled “Assessing the risks to the euro area financial sector from a no-deal Brexit – update following the extension of the UK’s membership of the EU”, ECB Financial Stability Review, May.

European Central Bank (2019b), “Macroprudential policy issues”, ECB Financial Stability Review, November.

Lysandrou, Photis, Nesvetailova, Anastasia and Palan, Ronen (2017), “The best of both worlds: scale economies and discriminatory policies in London’s global financial centre”, Economy and Society, 46:2, pp. 159 -184.

Pires, Fatima (2019), “Non-banks in the EU: ensuring a smooth transition to a Capital Markets Union”, SUERF Policy Note, Issue No 103, September.

- [1]For financial stability assessment of risks arising from a no-deal Brexit, see ECB (2019a).

- [2]Regulation (EU) No 600/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 (OJ L 173, 12.6.2014, p. 84).

- [3]Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and Directive 2011/61/EU (OJ L 173, 12.6.2014, p. 349).

- [4]Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on OTC derivatives, central counterparties and trade repositories (OJ L 201, 27.7.2012, p. 1).

- [5]Regulation (EU) No 909/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on improving securities settlement in the European Union and on central securities depositories and amending Directives 98/26/EC and 2014/65/EU and Regulation (EU) No 236/2012 (OJ L 257, 28.8.2014, p. 1 -72.).

- [6]EU financial services law currently includes around 40 provisions that allow the European Commission to adopt equivalence decisions. On this basis, the Commission has taken over 280 equivalence decisions for more than 30 countries, across various types of financial services, products and activities. See Equivalence/adequacy decisions taken by the European Commission for an overview.

- [7]See Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on equivalence in the area of financial services (2019).

- [8]For further details see ECB (2019a).

- [9]See Duffie et al. (2015).

- [10]Based on public data published by CCPs clearing OTC interest rate derivatives.

- [11]Data from LCH Ltd.

- [12]Euro-denominated repos on sovereign bonds are also cleared by BME Clearing (ES), Eurex Clearing (DE) and CC&G (IT). CC&G and LCH SA have an interoperability arrangement for the clearing of Italian sovereign bonds.

- [13]Total assets at the highest level of consolidation in the euro area.

- [14]Interest rate products, such as interest rate derivatives, are instruments whose value depends on increases and decreases in interest rates. Equity products are products with equities or equivalents as underlying (e.g. equity options, single-stock options or index return swaps). Credit products include debt securities in the trading book, securitisations and credit derivatives (e.g. credit default swaps and total return swaps). FX products are derivatives including all deals involving exposure to more than one currency, for example currency swaps or options.

- [15]See, for instance, Berger (1987).

- [16]G16 dealers are defined by the NY Fed as the group of banks which originally acted as primary dealers in the US Treasury bond market but nowadays happen also to be the group of largest derivatives dealers. The sample, which has world coverage, has changed over time and, currently comprises: Amherst Pierpont Securities, Bank of Nova Scotia, BMO Capital Markets Corp., BNP Paribas, Barclays, Bank of America, Cantor Fitzgerald, Citigroup, Crédit Agricole, Credit Suisse, Daiwa Capital Markets, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Jefferies, J.P. Morgan, Mizuho Securities, Morgan Stanley, NatWest, Nomura, RBC Capital Markets, Société Générale, TD Securities, UBS and Wells Fargo. See the list here. All G16 dealers are usually members of one or more CCPs with the role of clearing members.

- [17]“UK-based” in this case refers to the domicile of the trade’s counterparties and is identified via LEI codes. For example, it includes subsidiaries of US G16 dealers operating in the UK.

- [18]The analysis is performed without controlling for dealers’ securities portfolio. Net positions in derivative portfolios may also reflect hedging of other exposures such as loans, bonds or deposits. If UK banks had substantially larger directional exposures on the balance sheets, this could explain some part of their more directional derivatives positions vis-à-vis the euro area.

- [19]Gross exposures include a dealer’s matched book, which is commonly very large. If clients are able to buy or sell quickly and in volume, it is because a dealer is willing to take the other side of the trade without waiting for an offsetting customer trade. As a consequence, the dealer accumulates net exposures, sometimes long and sometimes short, depending on the direction of the imbalance. The ratio between net over gross exposures then represents the role of the dealer in making the market and providing immediacy to clients.

- [20]See Lysandrou, Nesvetailova and Palan (2017) for discussion.

- [21]See de Guindos (2020).

- [22]See ECB (2016).

- [23]See ECB (2019b), de Guindos (2019).

- [24]See ECB contribution to the European Commission’s consultation on the operations of the European Supervisory Authorities (June 2017) and Building a Capital Markets Union – Eurosystem contribution to the European Commission’s Green Paper (2015).

- [25]See Pires (2019).