- SPEECH

United we stand: European integration as a response to global fragmentation

Speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at an event on “Integration, multilateralism and sovereignty: building a Europe fit for new global dynamics” organised by Bruegel

Brussels, 24 April 2023

Recent developments have raised the question of how geopolitics will affect global economic relations in the 21st century.[1]

History suggests that the world is facing a trilemma, whereby peace, open trade and antagonistic political competition struggle to coexist. Open trade and peace can only be sustained if a stable political, economic and legal international order supported by common institutions offers a non-conflictual and enforceable way of dealing with disagreements.

This lesson was the basis for the creation of multilateral international institutions and European integration after the Second World War. They supported trade integration and facilitated access to capital, labour, natural resources and technology.

But in recent years severe geopolitical tensions have emerged, posing a threat to both peace and trade, and in turn to prosperity. These tensions increase the risks of multiple supply shocks destabilising prices and the economy, making it more difficult for central banks to deliver on their mandates.[2]

In this context, technology is taking on a crucial role. It remains a key driver of trade, notably in services. It offers an antidote to the effects of a possible reversal of globalisation by making it possible to use scarcer resources more effectively and reduce dependencies. And it supports growth by generating productivity gains. But it may exacerbate political competition as major powers strive for technological dominance.

Today, I will argue that closer European integration is the best response to global fragmentation. It provides us with the necessary foundation and scale to bolster our resilience to this fragmentation and our influence on international developments.

I will start by discussing the link between globalisation and the EU’s economic model. I will then turn to economic fragmentation and the changing nature of globalisation, emphasising the implications for the economy and monetary policy in Europe. And I will consider how the EU can pursue openness while preparing for fragmentation scenarios.

Globalisation and the EU’s economic model

In the aftermath of the Second World War, global trade integration underpinned by multilateral institutions aimed to reduce the risk of conflict. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)[3], signed in 1948, sought to liberalise trade and correct the protectionist measures that had been in place since the 1930s. In 1995 the World Trade Organization (WTO) replaced the GATT, providing the world economy with a negotiation forum where countries could address trade issues under the aegis of an agreed system of rules and a mechanism for solving trade disputes peacefully.[4]

Around the turn of the century, we entered a phase of globalisation “on steroids”[5] marked by a considerable increase in trade (Chart 1) and the integration of India and China into the world economy.

Chart 1

Developments in world trade since the 1870s

(Exports plus imports as a percentage of GDP)

Sources: Based on Klasing, M.J. and Milionis, P. (2014), “Quantifying the evolution of world trade, 1870–1949”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 92, No 1, January, pp. 185-197, and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Trade shares correspond to the sum of exports plus imports (from Barbieri, K., Keshk, O. and Pollins, B.M. (2009), “Trading Data: Evaluating our Assumptions and Coding Rules”, Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 26, No 5, November, pp. 471-491) over the reported estimated aggregate GDP. Estimated levels of aggregate GDP for 70 countries expressed in current-price US dollars and not adjusted for purchasing power differences.

This globalisation boom has had positive effects for the global economy overall,[6] as the reduction in tariff and non-tariff barriers[7] fostered trade, job creation, innovation and growth. The increasing participation in international trade has allowed emerging market economies to reduce the technology gap, improve institutional capacity and promote the accumulation of physical and human capital.

The EU has been a major contributor to the open trade system, achieving high levels of economic integration with the rest of the world. Trade flows between the euro area and the rest of the world reached 54% of euro area output in 2021, compared with 26% in the case of the United States. Regional and global integration has given the euro area an advantage over other advanced economies: by enhancing country specialisation and input sourcing possibilities, it has supported competitiveness and export market shares.[8]

But the EU’s reliance on exports was not complemented by adequate domestic investment and home-grown innovation. And the current circumstances highlight the significant risks of relying excessively on foreign demand as a growth engine. It can distract from the need to invest domestically and to improve competitiveness. And it can obscure the fact that dependencies on trade linkages can turn into vulnerabilities, allowing foreign players to weaponise them. Therefore, the EU needs to rely more on domestic demand – like other large, advanced economies – and reduce its dependencies.

Indeed, the euro area growth model largely relied on the assumption that an open multilateral economic order would continue to prevail in the future, guaranteeing continued access to relatively cheap imported resources, critical raw materials and technology. Investing in openness was often seen as a substitute for domestic investment in our physical, human and social capital.

It is now clear that these favourable conditions can no longer be taken for granted. We therefore need to rebalance the EU’s economic model.

Challenges for the European economy

Fragmentation pressures

The principle of multilateral cooperation – which most countries had until recently adhered to – is now facing formidable challenges, which are leading to fragmentation in international trade and finance.

The shocks that have hit the world economy have exposed the flip side to economic interdependence, which is vulnerability. Geopolitical risks have triggered a flight to safety, and many countries are putting an emphasis on greater autonomy.

While this is not a new trend, it is a fact that protectionist tendencies – which had already increased in 2017-18 with the trade dispute between the United States and China – increased further after the COVID-19 pandemic (Chart 2). And they have intensified further still following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The EU – for decades a champion of openness and integration – has developed its Open Strategic Autonomy agenda in order to prevent dependencies becoming vulnerabilities.[9]

Chart 2

Measures harmful to trade in net terms

(Number of measures “harmful” to trade globally, net of “liberalising” measures)

Source: Global Trade Alert and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Global Trade Alert classifies trade interventions announced by a government body in terms of the direction of change in the relative treatment of foreign versus domestic commercial interests. For instance, interventions that discriminate against foreign commercial interests are labelled as “harmful”, while interventions that liberalise on a non-discriminatory basis (i.e. most favoured nation as per WTO regulations) are labelled “liberalising”.

Geopolitical tensions and global fragmentation could entail high economic costs. Simulations by Eurosystem staff show that a fragmentation of the world economy would lead to sizeable losses in both global trade and welfare.[10] The EU thus needs to continue working towards safeguarding trade openness while increasing its own resilience to fragmentation.

The changing nature of globalisation

So far, the levelling-off of global trade in goods since the great financial crisis can be characterised as a phase of “slowbalisation” rather than “deglobalisation”.[11] In the services sector, the growth of international trade seems to be signalling a continuation of globalisation trends driven by technological progress.[12] Overall, aggregate data do not point towards deglobalisation, at least not for now.

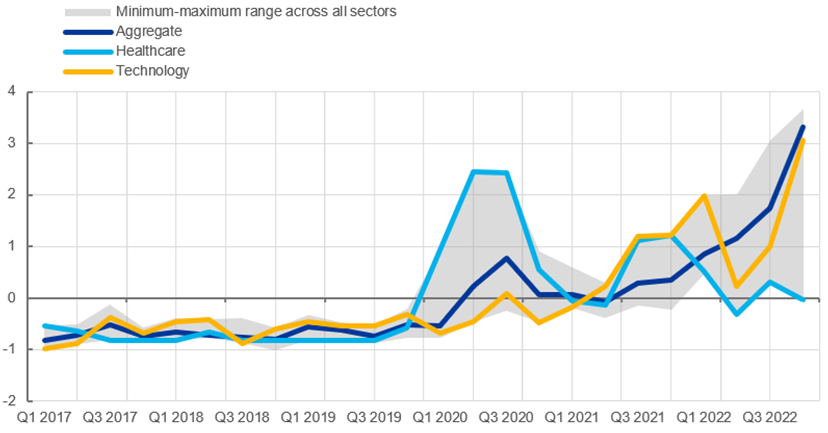

At the same time, the nature of globalisation may be changing. Firms are becoming more inclined towards nearshoring, onshoring or friend-shoring their supply chains, especially for the production of advanced technologies (Chart 3).[13]

Chart 3

Incidence of terms related to supply-chain reshoring in firms’ earnings calls by sector

(standard deviations away from the average number of mentions)

Sources: NL Analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The index captures the exposure (average number of mentions) of terms related to nearshoring, onshoring and friend-shoring in the transcripts of individual firms’ earnings calls. Global firms are considered, of which 50% are US firms and 23% are EU firms, based on the country of incorporation, if available. Ten sectors are considered: academic and educational services, basic materials, consumer cyclical goods, consumer non-cyclical goods, energy, financials, healthcare, technology, real estate, and utilities. The latest observations are for the fourth quarter of 2022.

Moreover, foreign direct investment in strategic sectors is becoming more fragmented, primarily to the detriment of Asian countries.[14] For instance, large US chip companies are showing a long-term commitment to moving their manufacturing plants back to the United States, also in response to the US CHIPS and Science Act.[15] These pledges mark a significant shift in the ability of US industry to manufacture semiconductors after two decades of dependence on offshore production.[16]

Implications for the EU economy and the ECB’s monetary policy

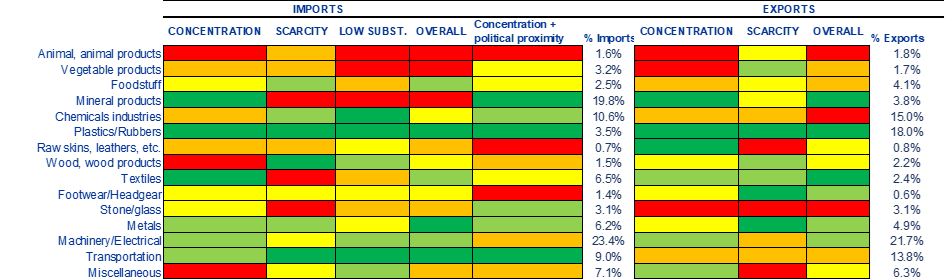

This new state of affairs poses challenges for the EU economy and the ECB’s monetary policy. Weaker trade integration could significantly reduce welfare because our economy is one of the most open and outward-oriented large economies. Its interdependencies could therefore turn into vulnerabilities (Chart 4).

Chart 4

Summary heatmap of EU trade dependencies

Sources: CEPII-BACI database, Bailey et al. (2017) and own calculations.

Notes: The heatmap uses indicators of concentration, scarcity and substitutability (subst.) as defined in Box 2.1 of International Relations Committee Work stream on Open Strategic Autonomy (2023), op. cit. Sector-specific indicators are standardised by the mean and the standard deviation for the whole sample. Sectors are then classified and colour coded according to the quintile to which their z-scores belong, with scores closer to red signalling higher vulnerability. Individual indices are also aggregated to obtain an indication of “overall dependency”. The fifth column shows the import concentration index in which import shares are weighted with an indicator of “political proximity”, based on UN voting patterns and calculated following Bailey et al. (2017).

Fragmentation may also affect the ECB’s monetary policy. Geopolitical shocks may trigger persistent output and inflation volatility, with multiple spillovers.[17] Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has, for instance, disrupted energy and commodities markets, with major implications for inflation.

Moreover, the evolving nature of globalisation could influence the natural rate of interest. Efforts to diversify imports and reduce foreign dependencies on specific countries may reduce productivity and curb the demand for safe assets coming from these countries, pushing up global interest rates. Capital movements and financing conditions could also be affected. At the same time, changes in international labour supply may affect the composition and dynamics of domestic labour markets, causing mismatches, changes in wage-setting relations and wage rises in the longer run.

Dealing with fragmentation

In this environment, the challenge is to pursue openness while preparing for fragmentation scenarios.

The way forward should include at least the following elements.

On the external front, the EU should continue to defend the principle of multilateralism, resisting the formation of closed blocs. A trade confrontation would lead to significant losses (Chart 5). We should not shy away from pursuing a more assertive role in fostering global cooperation. We should leverage our large internal market and significant share of global trade[18], while at the same time strengthening cooperation beyond close partners.

Chart 5

Change in EU27 trade flows in a trade fragmentation scenario

Source: Attinasi, M.G. et al. (2023), “Friend-shoring global value chains: a model-based assessment”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

Note: The non-linear impact is simulated through 25 iterations of the log-linearised model. In the left panel, the grey areas indicate the range between the flexible setup (yellow line) and the rigid setup (red line) and provide an illustration of the scope of the effects associated with the trade shock.

The EU should also diversify its participation in supply chains. The role that low-income countries can play in the EU’s supply chains should be considered further. Successful partnerships, including with low-income countries, could reduce the risk of value chains fragmenting along geopolitical blocs, especially in areas such as the green transition, where cooperation is vital and critical raw materials play an essential role.

The EU also needs to revisit its growth model, balancing external orientation with home-grown demand. The reasons are threefold. First, to remedy insufficient public investment and structural reforms, for which we should leverage European tools and objectives, as we did for the Next Generation EU. Second, to raise total factor productivity, which requires increasing investment in domestic research and cutting-edge civil and defence technologies. And third, to leverage the complementarity of Member States’ economies, using comparative advantages within the Single Market to reinforce European value chains, foster competitiveness and boost resilience to geopolitical shocks. This would also increase European cohesion and internal convergence.

European integration will also strengthen our ability to influence international developments. Well-coordinated, common EU action can be more effective at global level than isolated moves, especially when facing players of considerable economic and political weight.

Initiatives to deepen Economic and Monetary Union and strengthen the integration of the Single Market would also make our economy more resilient and stable, especially if backed by an appropriate common fiscal capacity. Such a fiscal capacity would support the necessary investment in EU public goods in areas such as the green transition, digital innovation and military spending.[19]

Policies aimed at increasing our strategic autonomy need to be carefully coordinated to ensure that they do not lead to internal fragmentation themselves. The EU’s strategic autonomy framework should avoid a counterproductive reliance on national solutions to global shocks, as this could bring about an internal race for subsidies, inefficient allocation of resources or unfair competition among EU Member States, exacerbating domestic economic divergences to the advantage of Member States with more fiscal space (Chart 6). The European Commission’s new Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework – which fosters public investment support in sectors which are key for the transition towards a net-zero economy – acknowledges this risk and includes several safeguards. Importantly, aid cannot trigger relocation of investments between Member States.[20] Undue protectionist policies that give a competitive edge to domestic industries may trigger beggar-thy-neighbour effects that undermine trust and openness.

Chart 6

Public debt and State aid expenditure in 2019

(as a percentage of 2019 GDP)

Source: European Commission.

Note: Data on general government debt and aid provided in 2019 are scaled by the GDP of the respective Member State during the same year.

Conclusion

There are no easy answers to geopolitical challenges that endanger peace, trade and prosperity, especially when the decisions steering geopolitics are beyond, or largely beyond, the control of domestic policymakers. Yet some of these decisions have severe consequences for the economies and policies of all countries. This was why in the aftermath of the Second World War a new global order was created – based on multilateral institutions – to buttress world trade.

But the current and future shape of the European Union and euro area is in the hands of Europeans. Closer European integration is the best response to global fragmentation. It gives us a stronger voice on the international stage to promote cooperation and openness. It provides the necessary scale to invest in technology and capitalise on domestic resources. And it is the right level on which to foster an open strategic autonomy that builds on the Single Market, rather than undermining it.

I would like to thank Demosthenes Ioannou, Maria Grazia Attinasi, Donata Faccia and Jean-Francois Jamet for their help in preparing this speech.

Panetta, F. (2022), “The complexity of monetary policy”, keynote speech at the CEPR-EABCN conference on “Finding the Gap: Output Gap Measurement in the Euro Area” held at the European University Institute, Florence, 14 November.

The original intention of the Bretton Woods Conference was to create a third institution, the International Trade Organisation (ITO), to deal with trade-related aspects of international economic cooperation and thus complement the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. At the same time, in December 1945 a group of countries (initially 15 and later 23) began talks on the GATT with a view to reducing custom tariffs. The GATT was signed in 1948 and, as the negotiation process to create the ITO ultimately failed, became the only multilateral instrument to govern world trade until the WTO was created in 1995.

Under the GATT, disputes were initially settled by a ruling by the chair. A working party was later established to consider the matter and advise the contracting parties. Finally, a more formal system involving a three-person “panel” was established. This concept was subsequently incorporated into the WTO. For more details, see McRae, D.M. (2021), “General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade”, United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law, June.

World Economic Forum (2019), “A brief history of globalization”, 17 January.

The fact that the number of members has increased from the 23 signatories of the GATT to the 164 members of the WTO is in itself an indication that free trade is appealing.

For example, in the Uruguay Round, which was concluded in 1995, developed countries cut their tariffs on industrial products by 40%, from an average of 6.3% to 3.8%, to be phased in over a five-year period. Moreover, the value of imported industrial products that receive duty-free treatment in developed countries jumped from 20% to 44%. For more information, see World Trade Organization, “Tariffs: more bindings and closer to zero”.

Work stream on globalisation (2021), “The implications of globalisation for the ECB monetary policy strategy”, Occasional Paper Series, No 263, ECB, September.

For an analysis of the EU’s economic interdependencies, the Open Strategic Autonomy agenda and the potential implications from a central banking perspective, see International Relations Committee Work stream on Open Strategic Autonomy (2023), “The EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy from a central banking perspective – challenges to the monetary policy landscape from a changing geopolitical environment”, Occasional Paper Series, No 311, ECB, March.

As per Campos R., Estefanía-Flores, J., Furceri, D. and Timini, J. (2022), “Trade Fragmentation”, Working Papers, Banco de España, simulations by Eurosystem staff that divide the world into three trading blocs – eastern, western and neutral – show that a fragmentation of the global economy taking us back to trade policy relations prevailing during the Cold War era would reduce exports from the eastern bloc to the western bloc by almost 20% and exports from the western bloc to the eastern bloc by roughly 27%. The neutral bloc would benefit from some trade diversion as it would attract some of the trade volume previously occurring between the two opposing blocs. The division into eastern, western and neutral blocks is based on how countries voted on the 7 April 2022 United Nations General Assembly Resolution concerning the suspension of the rights of membership of the Russian Federation in the Human Rights Council.

International Relations Committee Work stream on Open Strategic Autonomy (2023), op. cit.

For example, trade data show that the share of semiconductors and related manufacturing equipment imported into the United States from China has started to decline, replaced initially by imports from other East Asian countries and, since 2021, from Taiwan. Another indication of the drive towards friend-shoring can be seen in countries’ increasing adoption of foreign investment screening measures for reasons of national security. See IMF (2023), “World Economic Outlook: A rocky recovery”, April, pp. 91-114. McKinsey finds that over the period 2010-19 trade flows became more knowledge-intensive (i.e. professional services, government services, IT services and telecommunications) and they grew at a faster pace than trade in goods. See McKinsey (2022), “Global flows: The ties that bind in an interconnected world”, Discussion Paper, 15 November.

The IMF notes that “recent large-scale policies implemented by major countries to strengthen domestic strategic manufacturing sectors suggest that a shift in cross-border capital flows is about to take place. Most notable is a series of recent bills adopted against the backdrop of rising US-China trade tensions – such as the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the European Chips Act – that could affect multinational corporations’ production and sourcing strategies, prompting efforts to reconfigure their supply chain networks.” See IMF (2023), op. cit.

Investment flows to Asian countries started to decline in 2019 and have experienced only a mild recovery in recent quarters.

In late 2022 the Semiconductor Industry Association reported that such investments in the domestic industry amounted to close to USD 200 billion. For example, the US chip manufacturers Micron, Qualcomm (which are respectively among the top five and top ten manufacturers of semiconductors in the world) and GlobalFoundries have made public announcements to bolster their semiconductor production in the United States. According to available data from Bloomberg, most Qualcomm plants have been located in Asia until now.

Research conducted by the Financial Times finds that as a result of the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, the United States is attracting a significantly higher volume of new investments compared with 2019 and 2021, especially in the semiconductor and clean energy sectors. Moreover, Taiwan and South Korea appear to have been the largest foreign investors in the US semiconductor and clean-tech supply chain. The presence of euro area countries is much less significant, with only Germany reported as having announced new investments, for less than USD 10 billion. See Chu, A. and Roeder, O. (2023), “‘Transformational change’: Biden’s industrial policy begins to bear fruit”, Financial Times, 17 April.

Panetta, F. (2023), “Everything everywhere all at once: responding to multiple global shocks”, speech at a panel on “Global shocks, policy spillovers and geo-strategic risks: how to coordinate policies” at The ECB and its Watchers XXIII Conference, 22 March.

In 2021 the EU was the second largest WTO trading partner after China, followed by the United States. See also Wolff, A. W. (2023), “The world trading system needs a more assertive European Union”, Realtime Economics, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

An important example in this context is the green transition and the recent surge in energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Europe relies heavily on imports of critical raw materials (which are indispensable for the green transition) from quasi-monopolistic third-country suppliers, which leaves it exposed to significant geopolitical risks. It will be necessary to significantly scale up investment in a number of sectors, from the extraction of critical raw materials to recycling and innovation. If we consider EU resilience to the weaponisation of energy a public good, given the associated risk of market failures, there is a strong case for a common fiscal response.

Communication from the Commission on Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework for State Aid measures to support the economy following the aggression against Ukraine by Russia (2023/C 101/03), 17 March 2023.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts