Monetary policy, exchange rates and capital flows

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the 18th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., 3 November 2017

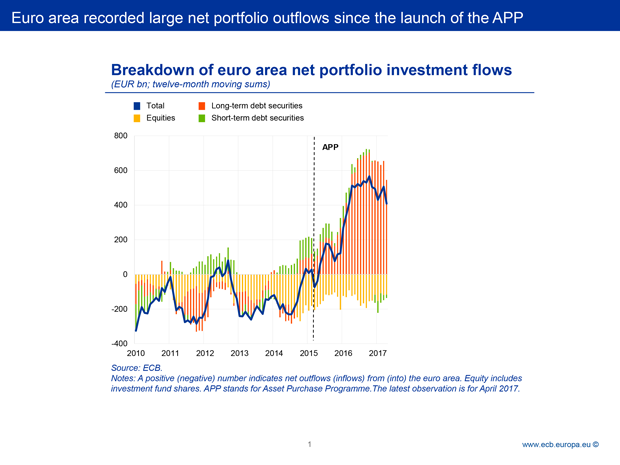

Central bank asset purchase programmes are often catalysts for significant cross-border capital flows. [1] By compressing the (excess) return on domestic bonds, they encourage investors to rebalance their portfolios towards foreign, higher yielding assets.[2] Such capital flows have reached historical dimensions in the case of the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP), with both resident and non-resident investors moving out of euro-denominated securities and into bonds issued predominantly by the safest non-euro area sovereigns. I examined these flows in detail in a recent speech at the ECB’s Foreign Exchange Contact Group meeting.[3]

One intriguing observation I made in this speech was that there was no evidence of a causal link between such capital flows and exchange rate movements. Findings based on event studies instead suggest that, around the time of central bank asset purchase announcements, investors price the exchange rate mainly on the basis of the information these programmes provide to markets about the expected future path of short-term interest rates. In this sense, the effect of asset purchases on exchange rates is not fundamentally different from that of conventional interest rate policy.

Today I would like to build on this previous contribution and provide further insights into the channels through which central bank asset purchase programmes are likely to affect the exchange rate. I will provide suggestive evidence that challenges the widely held view in the event-study literature that policy-induced portfolio rebalancing does not affect the exchange rate.[4] My remarks therefore confirm that portfolio rebalancing is a major transmission channel of central bank asset purchase programmes and provide some tentative support to theories of exchange rate determination in imperfect financial markets, which give a first-order role to capital flows.[5]

Unlike private portfolio rebalancing, however, central bank asset purchase programmes can be anticipated by investors. This means that exchange rates should adjust in a way that clears the expected future supply of and demand for currency resulting from anticipated cross-border capital flows. The implication is that asset purchase programmes may, at times, break the link between future expected short-term rates and the exchange rate.

Before developing this argument in more detail, allow me to reiterate at this point that the exchange rate is not a policy target for the ECB. It is one channel of transmission through which our monetary policy actions achieve price stability in the medium term, in both conventional and unconventional times. It is therefore important that practitioners and academics alike better understand how this channel propagates policy stimulus through financial markets, within and across economies.

The zero lower bound, forward guidance and exchange rates

Let me start by briefly recalling the two main propositions I made in my earlier remarks in July. One was that there is compelling empirical evidence that central bank asset purchase programmes are often associated with substantial cross-border capital flows. My first slide illustrates this point quite clearly for the euro area.

The second proposition was that asset purchases affect the exchange rate in broadly the same way as conventional monetary policy – that is, through expectations of interest rate differentials. To date, there is very little evidence to suggest that currency movements are a direct consequence of the impact on the supply of and demand for currency when investors rebalance their portfolios across borders.

It is this second proposition that I would like to examine today in greater detail.

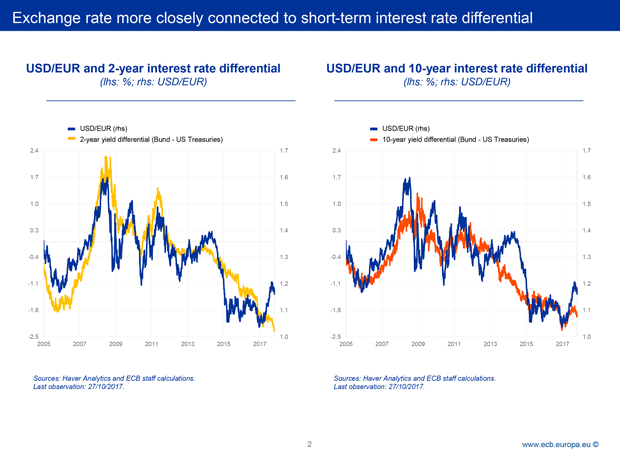

In doing so, it is helpful to start by recalling the basic relationship between exchange rates and interest rate movements. I do this on the second slide. On the left-hand side you can see that, in the past, there has often been an intimate relationship between short-term interest rate differentials – measured here using bonds with a maturity of two years – and movements in the exchange rate, at least for the euro and US dollar pair. The correlation between the two series was a remarkable 0.85 during the period 2005 to 2011.

Admittedly, academics typically take this correlation much less seriously than practitioners. It is a good habit of academics to dismiss contemporaneous correlations between two variables as spurious. If anything, standard theory – also known as uncovered interest parity (UIP) – predicts a correlation between today’s interest rate differentials and tomorrow’s exchange rate changes, thereby discrediting any perceived contemporaneous causality.

Other approaches are less dismissive, however. The “asset market approach” to exchange rates, for example – which, in essence, is an alternative representation of the UIP – posits that, as an asset price, exchange rates should fully reflect today’s expectations about the future, just as equity prices reflect the expected discounted stream of future earnings and other relevant information.[6]

The implication is that the current level of the exchange rate should be a function of the average of current and future expected short-term interest rates. And because monetary policy, away from the zero lower bound, predominantly sends signals about the current level of central bank interest rates, and because the term premium – the additional return that investors demand for the risks incurred by not simply rolling over a series of short-term bonds – was typically contained at shorter horizons, it is not surprising to see a strong correlation between short-term interest rates and the exchange rate.

Long-term interest rate differentials, by contrast, have usually carried less informational content to explain exchange rate movements. You can see this on the right-hand side of this slide. There was a connection, but it was looser, around 0.65, likely reflecting the growing role of term premia along the term structure of interest rates.[7]

So, prima facie, empirical evidence suggests that monetary policy, by influencing short-term interest rate differentials, could directly affect the exchange rate and, hence, real activity and prices. A natural question to ask, then, is whether monetary policy may have lost some of its potency once interest rates reached the zero lower bound. That is, policy might have become less effective once it started working its way mainly through long-term, rather than short-term, interest rates, via, for example, sovereign bond purchases.

Simple visual inspection of the chart on the left suggests it has indeed. As two-year interest rates approached the zero lower bound – around end-2011 – their correlation with the exchange rate effectively broke down. Long-term rates, at least initially, also seem to have provided little to no information as to where the exchange rate was heading, as the chart on the right suggests.

This interpretation warrants closer inspection, however, as this period coincided with the growing use of unconventional monetary policy measures by central banks worldwide. Indeed, I will argue that in order to understand how unconventional policy affects the exchange rate at, or close to, the lower bound, it is useful to break down long-term yields into their two main components – the expectations component and the term premium.

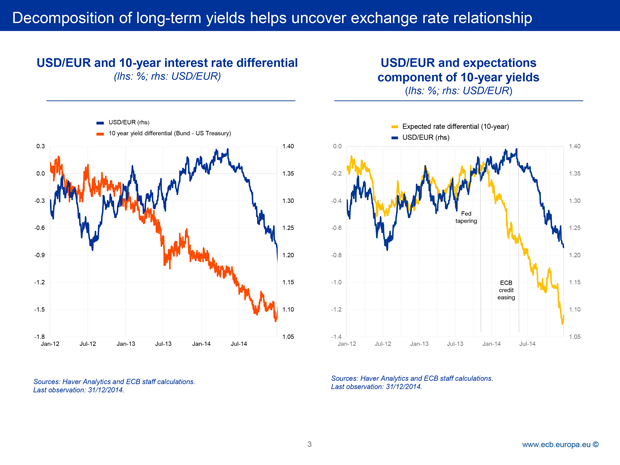

Slide 3 shows the insights that can be gained from this breakdown. Here I focus on the period 2012 to 2014. During this period, short-term rates barely moved, as you saw on the previous slide, while the long-term interest rate differential was by and large disconnected from exchange rate movements – you can see this clearly again on the left-hand side.

But now consider the right-hand chart. Here I plot the exchange rate against the differential of the expectations component of ten-year interest rates as extracted from dynamic term structure models.[8] Put simply, it is the same ten-year rate differential as on the left-hand chart, only corrected for the term premium estimate.

The correlation during 2012 and 2013 is compelling, at around 0.75. Shortly before the crisis, in 2005 and 2006, the correlation was less than 0.4. Incidentally, the close relationship coincides with a considerable strengthening of central banks’ forward guidance on interest rates. The Federal Reserve, for example, introduced date-based forward guidance in mid-2011 and adopted state-contingent guidance in late 2012. The ECB, for its part, introduced rate forward guidance for the first time in July 2013, one year before it announced its credit easing programme.

So, what could have happened is that market participants, trusting central banks’ forward guidance that policy rates would stay at very low levels for an extended period, were increasingly pricing exchange rates on the basis of information about how policy would evolve in the more distant future. That is, with short-term rates broadly stable, the weight investors attached to the expected future path mechanically increased – just as theory would predict.[9]

Term structure models can therefore provide compelling evidence that exchange rates remain deeply connected to monetary policy also when interest rates are at, or close to, the effective lower bound, even if interest rate differentials per se suggest a structural break in the relationship.

Asset purchases and exchange rates

But the right-hand chart also suggests that this is not the full story. A clear break emerged in late 2013. And that break is likely related to the second policy instrument I mentioned before, namely asset purchases. Although asset purchases, by removing duration risk from the market, act primarily on the term premium, they also entail a strong signalling channel, in particular at, or close to, turning points.

For example, the Federal Reserve’s decision to start tapering in December 2013 triggered an appreciable increase in future expected short-term rates. You can see on the right-hand side that the ten-year expectations component differential vis-à-vis the euro area widened by more than 50 basis points in just a few months. This should have caused the US dollar to appreciate, at least on the basis of past behaviour.

The dollar defied upward pressure, however. It continued to depreciate persistently, despite the marked widening in future expected interest rates. One reason why this might have been the case is that the signalling and the portfolio rebalancing channels of asset purchases might have worked in opposite directions. In imperfect markets, investors may give different weights to conflicting information.

What I mean by this is that, despite expectations of a significant increase in policy rates, the Federal Reserve’s very gradual slowdown of its pace of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities purchases – which caught many investors on the wrong foot after the “taper tantrum” – possibly fuelled expectations that long-term rates, and hence also foreign demand for US-denominated interest-bearing assets, would remain contained for a considerable period.

This interpretation is consistent with at least four observations: first, term premia on US bonds fell notably after the Federal Reserve started tapering in December 2013, pointing to a correction of the sharp uptick in term premia after the “taper tantrum”.[10] Second, investors did not expect the US dollar to appreciate. CFTC data show that they continued to hold net short speculative positions in the US dollar well into 2014. Third, capital inflows into the US Treasury market did indeed decelerate somewhat during the first half of 2014, validating earlier expectations. And, fourth, the dollar started to appreciate only once expectations about asset purchases in the euro area gained a strong tailwind during the second half of 2014.

Here the temporal coincidence is striking. The moment the ECB announced its credit easing programme in June 2014, which many observers considered to be a harbinger of sovereign bond purchases, and moved rates into negative territory, the dollar started to appreciate significantly against the euro.

In less than two and a half months, the euro lost nearly 10% in value. Net euro short positions jumped to close to record highs in the space of a few weeks. In other words, only the prospect of sovereign bond purchases by the ECB seems to have led to a reappraisal by market participants of future domestic and foreign demand for US Treasuries.[11]

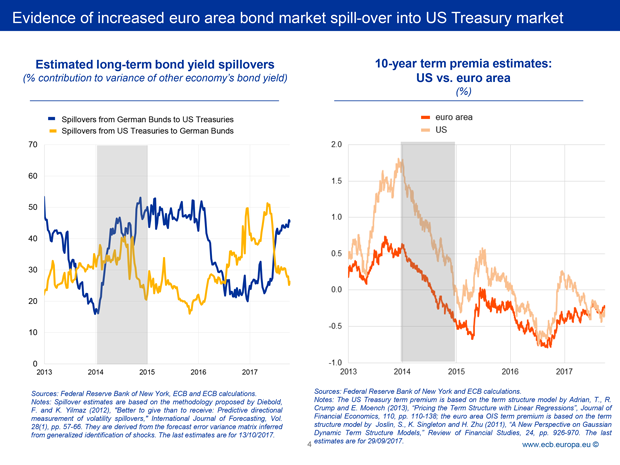

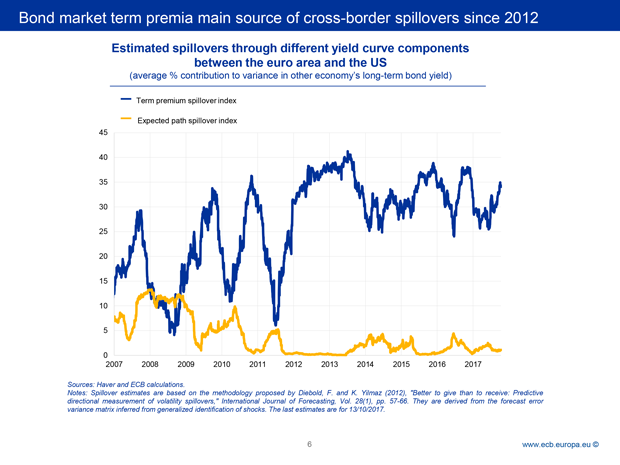

Empirical analysis on the direction of international spillovers in bond markets corroborates this view. On slide 4 you can see that ECB researchers, using the Diebold-Yilmaz methodology, find that spillovers from the euro area to the United States spiked sharply in mid-2014.[12] According to this methodology, euro area spillovers accounted for more than half of the variance in US Treasuries in the second half of 2014.

Put differently, in the presence of asset purchase programmes, the portfolio rebalancing channel, rather than the signalling channel, might ultimately rise to become the dominant driver of exchange rates, at least temporarily. Expectations of compressed term premia, either through central bank actions directly, or through cross-border capital flows associated with such programmes, or both, can offset, or mitigate, the impact of changes in the expectations about future short-term rates on exchange rates.

Disconnects may also be the result of market segmentation, much in line with the view that the financial market comprises a heterogeneous set of actors with very different beliefs and expectations. Indeed, the same chart suggests that spillovers from the euro area to the US bond market had already accelerated sharply in the first half of 2014. So, a good part of the decline in US term premia during this period – you can see this on the right-hand side – might in fact have reflected expectations about monetary easing in the euro area, paired with a reappraisal of the Federal Reserve’s policies.

In other words, during this period participants in the bond market might have held, on average, a different view on the prospects of global monetary policy from that of their counterparts in the foreign exchange market, which maintained sizeable net long positions in the euro. Christopher Sim’s “rational inattention” comes to mind.[13]

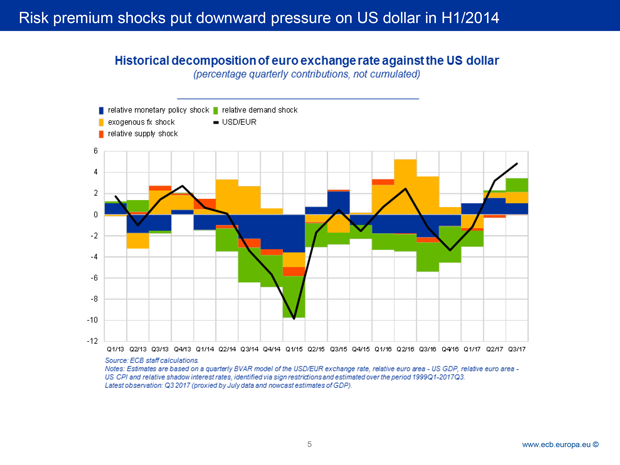

This can also be seen on the next slide. Here I show a breakdown of the historical drivers of the euro and US dollar exchange rate based on a Bayesian VAR developed by researchers at the ECB.[14] The shocks are identified using standard sign restrictions. The breakdown suggests that, by contrast with the spillovers we saw in the previous chart, monetary policy shocks seem to have contributed comparatively little to exchange rate movements in the first half of 2014.[15]

Instead, an exogenous shock, which can be interpreted in the context of this discussion as a time-varying risk premium shock, appears to have put mainly downward pressure on the dollar. To the extent that risk premium and bond term premium shocks are driven by the same fundamentals, this would be consistent with the view that the signalling and portfolio rebalancing channels were sending conflicting signals.

This train of thought is in fact very similar to the view put forward by Charles Engel and Kenneth West on the relationship between risk premia and the exchange rate.[16] They saw the dollar depreciation in 2007 as evidence of investors thinking “this is a US crisis”. And they saw the dollar appreciation in 2008 as a change in this thinking to “well, this is actually more of a global crisis”.

As with the events of 2007-08, what ultimately caused the initial resilience of the dollar and the sharp fall in term premia in 2014 will remain a matter of speculation. Factors other than the actions of the Federal Reserve and the ECB are likely to have contributed to these developments. But that is not my point. My point is rather that it is not surprising that central bank asset purchases may break with some of the regularities we have become used to.

The reason is that asset purchases are monetary policy actions that can be anticipated by market participants, just like changes in key policy rates. Unlike conventional monetary policy, however, they have direct implications for the expected supply of and demand for internationally traded bonds and, hence, for the level of the exchange rate that, all other things being equal, clears the resulting capital flows.

This may, at times, break the link between future expected rates and the exchange rate. This is clearly visible when we look at slide 6. The chart is based on the same methodology as the spillover chart on slide 4, but it illustrates how much, on average, of the variance in long-term bond yields in one country can be explained by the other country’s term premium and expected short-term rates respectively.

You can see that the moment short-term yields hit the zero lower bound, spillovers in bond markets by and large reflected term premia movements – in both directions. These spillovers may pull the exchange rate away from the path implied by expectations about the future short-term rate. The extent of the decoupling, in turn, will depend on the expected direction, persistence and degree of international spillovers – something that is inherently difficult to project and price.

In this sense, the implications are very similar to those described by Xavier Gabaix and Matteo Maggiori in their 2015 Quarterly Journal of Economics article, which states that the risk-bearing capacity of financial intermediaries provides a role for capital flows to affect the exchange rate.[17] The difference is only that if asset purchases are understood by investors to be part of the reaction function of central banks, then the exchange rate can be expected to adjust before capital flows take place. This is certainly what we have seen in the euro area.

This also means that we should treat more carefully findings in the event-study literature that assign most of the observed exchange rate change around central bank asset purchase announcements to the signalling channel.[18] Given that intermediaries are forward-looking but constrained by their balance sheets, policy-induced exchange rate changes can also be expected to reflect expectations of future cross-border capital flows and their associated impact on the future supply of and demand for currency.

In this sense, the debate also shares some similarities with a related strand of the literature, namely the transmission channels of sterilised foreign exchange interventions. The view that such interventions are effective mainly by signalling future policy intentions is frequently challenged by empirical evidence suggesting that portfolio rebalancing may have economically relevant effects.[19]

Of course, this does not mean that understanding the potential spillovers of central bank asset purchase programmes is enough to explain exchange rate movements. Changes in relative term premia are far more difficult to interpret than changes in the expected path of future short-term interest rates. The latter can be clearly associated with changes in monetary policy expectations. Changes in term premia, by contrast, often reflect a combination of shocks, including monetary policy shocks as well as shocks to demand, risk aversion and other variables, which will drive term premia in the same or in opposite directions.

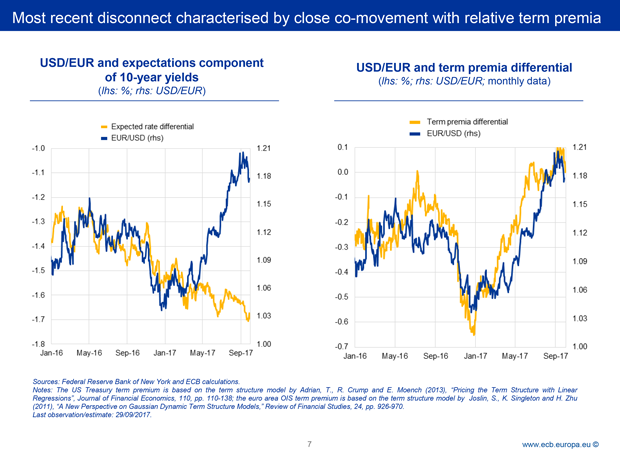

The most recent disconnect between the euro and US dollar exchange rate and the expected future short-term interest rate differential is a case in point. On the left-hand side of slide 7 you can see that a significant gap between the two series re-emerged in the spring of this year, and continues to persist.

It is tempting to link recent developments once more to portfolio rebalancing considerations. After all, the Federal Reserve is now actively reducing its balance sheet, while the ECB last week decided to extend its asset purchase programme by nine months, or more, if needed, while reducing the monthly pace to €30 billion. This might have caused some investors to expect a gradual rebalancing of portfolios away from US dollar-denominated assets and towards euro-denominated assets, which would support the euro.

But many other factors may drive interest and exchange rates, with likely different implications for the real economy.[20] Indeed, geopolitical and policy uncertainties may also contribute to swings in bond term premia. So it is difficult to establish unequivocal links. But, if we look at the right-hand side of this slide, it is intriguing to see such a close relationship between the exchange rate and relative bond term premia differential as that observed during the course of this year.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Deciphering exchange rate movements, and giving them a structural interpretation, remains a topic that requires the dedication and passion of many researchers. Much has already been learned, but much still remains to be understood. The introduction of unconventional monetary policy measures forces us to think more deeply about the channels through which such measures affect the exchange rate, with regard to their impact both on the expected future path of short-term interest rates and on risk premia.

An important aspect in this endeavour is to gain a better understanding of the role of portfolio rebalancing. Evidence is growing, and my remarks today are intended to add to this, that portfolio rebalancing is a major transmission channel of central bank asset purchases. At the same time, the signalling and portfolio rebalancing channels of central bank asset purchase programmes might, at times, work in opposite directions, with unclear implications for the exchange rate.

Moreover, in an integrated global financial system, unconventional policy measures have been shown to often trigger large cross-border capital flows. To the extent that such policies can be anticipated by market participants, financial intermediaries could be expected to price in the resulting shift in the relative supply of and demand for currency before capital flows take place. As a consequence, international portfolio rebalancing considerations may, at times, drive a wedge between expected future short-term rates and the exchange rate.

My remarks today are by no means conclusive and they are based on tentative evidence. But I hope that they provide impetus to further, more systematic research on a topic that is not only intriguing from an intellectual perspective, but also of significant relevance to policymakers in their efforts to improve the understanding of the transmission channels of non-standard monetary policy measures.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] I would like to thank T. Kostka, A. Mehl, I. Van Robays and J. Gräb for their contributions to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

[2] See e.g. Fratzscher, M., M. Lo Duca and R. Straub (2016), “ECB Unconventional Monetary Policy: Market Impact and International Spillovers”, IMF Economic Review, 64(1), pp. 36-74; Georgiadis, G. and J. Gräb (2016), “Global Financial Market Impact of the Announcement of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme”, Journal of Financial Stability, 26, pp. 257-265; Rajan, R. (2014), “Competitive monetary easing: is it yesterday once more?”, remarks at the Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C., April 10; and Bernanke, B.S. (2015), “Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context”, paper presented at the 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C., 5 and 6 November.

[3] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “The international dimension of the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the ECB’s Foreign Exchange Contact Group meeting, Frankfurt am Main, 11 July.

[4] See e.g. Fratzscher et al. (2016, op.cit.) and Georgiadis, G. and J. Gräb (2016, op.cit.).

[5] See e.g. Gabaix, X. and M. Maggiori (2015), “International Liquidity and Exchange Rate Dynamics,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(3), pp. 1369-1420; and Hau, H. and H. Rey (2004), “Can Portfolio Rebalancing Explain the Dynamics of Equity Returns, Equity Flows, and Exchange Rates?”, American Economic Review, 94, pp. 126-133.

[6] See e.g. Engel, C. and K.D. West (2005), “Exchange Rates and Fundamentals”, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 113(3), pp. 485-517; Froot, K.A. and T. Ramadorai (2005), “Currency Returns, Intrinsic Value, and Institutional-Investor Flows”, Journal of Finance, 60, pp. 1535-1566; and Engel, C. and K. West (2010), “Global Interest Rates, Currency Returns, and the Real Value of the Dollar”, American Economic Review, 100, pp. 562-567.

[7] A second explanation could be that exogenous monetary policy shocks may have less impact on long-term interest rates (see e.g. Evans, C.L. and D.A. Marshall (1998), “Monetary Policy and the Term Structure of Nominal Interest Rates: Evidence and Theory”, Carnegie Rochester Series on Public Policy, 49, 1998, pp. 53–111).

[8] For more details on estimates of US term premia, see e.g. Adrian, T., R. Crump and E. Moench (2013), “Pricing the Term Structure with Linear Regressions”, Journal of Financial Economics, 110, pp. 110-138. For the euro area term premia, the breakdown is based on an affine term structure model fitted to the euro area OIS curve using the method described in Joslin, S., K. Singleton and H. Zhu (2011), “A New Perspective on Gaussian Dynamic Term Structure Models”, Review of Financial Studies, 24, pp. 926-970.

[9] The evidence presented here seems at odds with the predictions made in Galí, J. (2017), “Forward Guidance and the Exchange Rate”, mimeo.

[10] This happened despite US medium-term inflation expectations as well as crude oil prices moving mostly sideward during this period, with a stable world economic outlook as depicted by the IMF.

[11] Many market commentaries also considered that the speech by ECB President Mario Draghi in August 2014 in Jackson Hole provided signals that the ECB was considering purchases of sovereign bonds in response to a destabilisation of medium-term inflation expectations. See Draghi, M. (2014), “Unemployment in the euro area”, speech at the annual central bank symposium in Jackson Hole, 22 August.

[12] For more details about the methodology, see Diebold, F.X. and K. Yilmaz (2012), “Better to Give than to Receive: Predictive Directional Measurement of Volatility Spillovers”, International Journal of Forecasting, 28, pp. 57-66.

[13] See Sims, C. (2003), “Implications of Rational Inattention”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 50 (3), pp. 665–90. The ability of the foreign exchange markets to process all relevant information has been subject to close scrutiny, see e.g. Froot, K.A. and R.H. Thaler (1990), “Anomalies: Foreign Exchange”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4 (3), pp. 179–92.

[14] See also Cœuré, B. (2017), “The transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy in standard and non-standard times”, speech at the workshop “Monetary policy in non-standard times”, Frankfurt am Main, 11 September.

[15] This is apparent when the first two quarters of 2014 are put together in the chart on slide 5.

[16] See Engel, C. and K. West (2010, op.cit.).

[17] See Gabaix, X. and M. Maggiori (2015, op.cit.).

[18] See e.g. Rogers, J., C. Scotti and J. Wright (2014), “Evaluating Asset-Market Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy: A Cross-Country Comparison”, International Finance Discussion Papers 1101, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Fratzscher et al. (2016, op.cit.); and Georgiadis, G. and J. Gräb (2016, op.cit.).

[19] See Sarno, L. and M. Taylor (2001), “Official Intervention in the Foreign Exchange Market: Is It Effective and, If So, How Does It Work?”, Journal of Economic Literature; and Blanchard, O., G. Adler and I. de Carvalho Filho (2015), “Can Foreign Exchange Intervention Stem Exchange Rate Pressures from Global Capital Flow Shocks?”, NBER Working Paper21427. Non-sterilised interventions, which in spirit are closest to central bank asset purchase programmes, are widely considered to be effective through both channels (see e.g. Chinn, M. (2017), "The Once and Future Global Imbalances? Interpreting the Post-Crisis Record", paper presented at the annual central bank symposium in Jackson Hole, August).

[20] See Cœuré, B. (2017, op.cit.).

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts