Reflections on the exit strategy

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBSveriges Riksbank, Stockholm, 21 January 2010

A lot of attention has been devoted in recent policy discussions to the exit strategy from the expansionary monetary and fiscal policy stance adopted since the outbreak of the crisis, and to the interaction between the two. Designing an optimal exit strategy should, in theory, not be too difficult. In an ideal world, fiscal stimuli should be withdrawn before monetary policy is tightened in order to ensure that public debt remains sustainable and that monetary policy is not overburdened.

We know however that first-best solutions are often hard to implement, because they are based on unrealistic assumptions relating in particular to the rationality of expectations and the ability of policy-makers to rapidly make decisions and to change them if needed. Furthermore, policy-makers have to take account of the prevailing uncertainty and of the impact of their decisions on agents’ expectations. For instance, fiscal policy is normally decided once a year, through an elaborate budget process, but is not implemented until the following year. This process introduces significant rigidities into the decision-making and makes it somewhat less likely that fiscal policy can exit before monetary policy, which is typically a much more flexible instrument.

Today I would like to focus my remarks on the exit from the accommodative stance of monetary policy. I will not consider the phasing-out of the non-standard measures that central banks have adopted over the last few months.

The discussions so far have centred mainly on the timing of the exit decision, which should neither be premature nor tardy. There are counter-effects in both scenarios. If the decision to exit is made too early, the economic recovery may be put at risk, as higher interest rates will produce a tightening effect on consumption and investment decisions at the very time when the pick-up in the economy is still fragile. Furthermore, it might further restrict credit conditions while the banking system is still restructuring its balance sheet. If, on the other hand, the decision is taken too late, monetary conditions will remain too lax for too long, sowing the seeds of the next crisis. In addition, the later the tightening, the sharper it needs to be, thus producing valuation changes that may reduce banks’ profitability and undermine their ability to support the economic recovery.

Given the difficulty of the timing, the discussion has turned to the second-best option. In other words, which of the two risks – being too early or being too late – would pose the biggest problems for the economy? Several authors, including international organisations, have suggested that the policy authorities should err on the side of being late. They argue that an early tightening is difficult to reverse and tends to hit the economy early in its recovery, and may give rise to a double-dip recession. On the other hand, a late tightening allows more time to bring things back to normal. In addition, the stronger the economy is likely to be, the more resistant it will be to the shock produced by the tightening of monetary conditions.

Overall, history shows that policy authorities have largely erred on the side of being too late than of being too early. Indeed, late exits have been quite numerous; they were either the result of deliberate policy decisions to boost the economy, which was probably the case in the 1970s and early 1980s, or of forecast errors made in over-estimating deflationary risks and under-predicting the subsequent recovery, which might be the case of the decade just ended. [1]

The monetary and fiscal policy tightening that took place in the United States in 1936, which led to the 1937-38 recession, is regarded as a text-book example of too early an exit, of a mistake not to be repeated. There are not many other examples of early exits. The slight increase in interest rates by the Bank of Japan in 2000 has been considered by some as an early exit, but recent analysis has downplayed it. [2]

In fact, examining closely the 1936 episode in the US, it might not even be considered as an early exit. The very restrictive monetary and fiscal policies that were adopted at that time might deserve to be categorised as a case of ‘brutal’ exit, the effects of which could in fact have occurred at any time, exit or no exit. Between mid-1936 and early 1937 reserve requirements for banks were doubled in a series of three steps. The general government budget contracted by almost 4% of GDP. These measures appear to have been disproportionate, even with an economy that had started to recover, with inflation picking up and credit aggregates accelerating. The severe negative effects of these measures do not mean that no measure should have been taken at all. They should simply not have been so abrupt and not have taken economic agents by surprise. In other words, the 1936 episode might be considered as an example of a badly calibrated and badly communicated exit, rather than a wrongly timed exit.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the 1994 episode, when the Fed’s 25-basis-point increase in its funds rate caused turmoil in the bond market. Even with the benefit of hindsight, that decision can be regarded as neither tardy nor brutal. The problem was that it took markets by surprise and led to a major reassessment of the yield curve, with substantial valuation losses on long-term positions.

These experiences confirm that not only is the timing of the exit crucial, but also its communication to market participants. Indeed, the impact of any withdrawal of monetary stimulus on financial market participants depends on whether they have fully anticipated it. If they have, then the decision tends to have less impact on the yield curve, and thus on the valuation of banks’ assets and on the rate that banks charge to their customers, especially on fixed rate loans. As confirmed by a growing body of literature, the main mistake relating to the 1936-37 decisions was that they were badly communicated to economic agents. [3]

To sum up, a key element of the exit strategy is that the policy authorities must guide expectations. How can they do this?

Let me first of all consider how it should not be done.

First, it may be better for central banks not to become embroiled in the debate on whether exiting too early or too late is better or worse, and especially not to give signals that the latter is less risky. Such an approach could encourage market participants to become less risk-averse and to expect the period of low interest rates to be extended beyond what is necessary. This would induce them to take on further risks, in particular in terms of maturity mismatches – borrowing short-term to buy long-term bonds – which might be profitable in the short term but could lead to substantial capital losses when the exit takes place.

Second, any commitment to prolonged periods of low interest rates is risky. If the aim is to lower long-term rates, it may also encourage market participants to take substantial long positions in the fixed income market. As a result, the risk of major losses arising at the time of the exit increases considerably, as the 1994 experience shows. This may induce the central bank to further delay the exit to avoid penalising banks. This seems to be the experience of 2002-2004. As a result, interest rates may remain below the desired level for too long, fuelling a possible bubble.

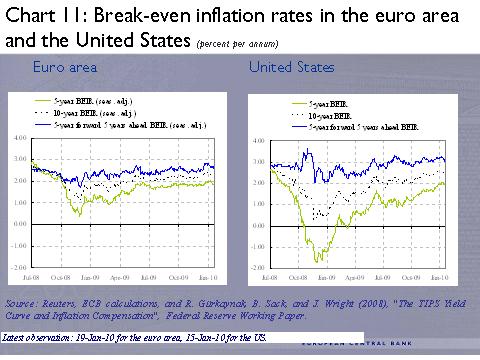

Third, central banks need to be very careful in using information extracted from market data when conducting monetary policy. The anchoring of inflation expectations is a very important benchmark for assessing whether the stance of monetary policy has become too expansionary and whether there are risks of falling behind the curve. However, the pre-crisis period and the crisis itself have shown that expectations are not always formed in a rational way and might themselves be influenced by the behaviour of the monetary authorities. Quite often markets participants form their expectations by looking at central banks’ behaviour, on the assumption that the latter have better and more information about underlying inflationary pressures. Under these circumstances, market-based inflation forecasts tend to be biased and may react in a perverse way following a tightening of monetary policy. In particular, inflation expectations may be revised up, rather than down, after an interest rate increase, especially at the beginning of a tightening cycle. If the monetary authorities’ assumption that inflation expectations are well anchored proves to be wrong, the whole yield curve might move upwards and the decision to increase the rate of interest may result in a much sharper tightening than expected. [4]

Another problem with inflation expectations concerns their measurement, especially in periods of financial turbulence, when the liquidity of the underlying instruments can affect their signalling content. A further distortion may arise when the central bank is itself a major buyer and holder of indexed-linked assets, which may distort prices and thus the information content. Measurement problems arise also with other components of the analytical framework, such as the output gap. Experience shows that measurement of the output gap varies over time. For instance, when measured ex post, with the data available until 2008, the US output gap over the period 2002-2004 turned out to be very small, even non-existent, while ex ante it was estimated at around 2% of GDP. [5]

So what should a central bank do to implement and communicate an appropriate exit strategy? Let me make a few comments on this.

To ensure that the exit strategy does not come as a complete surprise, it has to be well communicated. Over recent months, central banks have devoted a lot of time to explaining their exit strategies, both in terms of content and conditions. At the ECB we have made it clear that, as in the past, any decision – even one concerning the exit – will be linked to the underlying economic conditions and in particular to the re-emergence of inflationary pressures. Market participants should thus form their expectations on future interest rates on the basis of projected economic developments rather than on specific unconditional commitments.

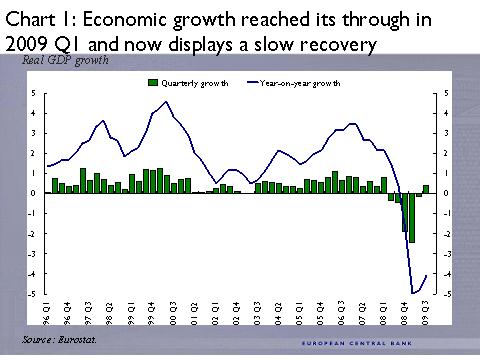

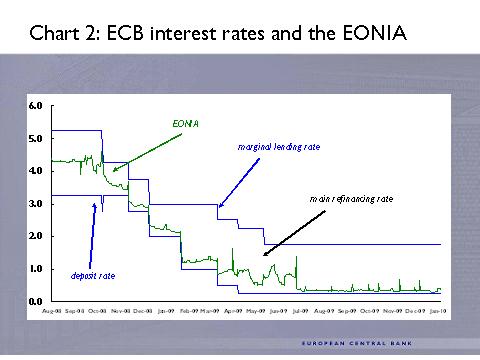

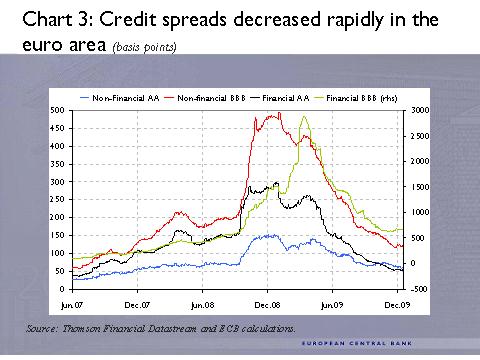

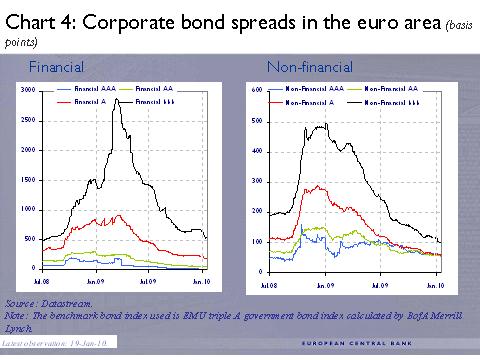

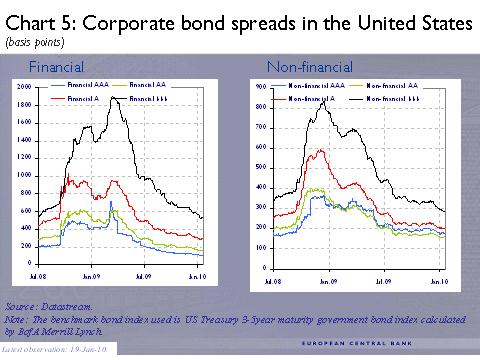

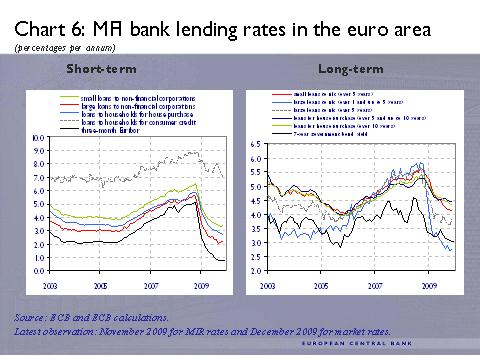

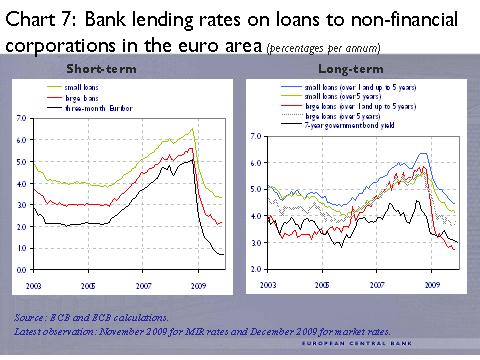

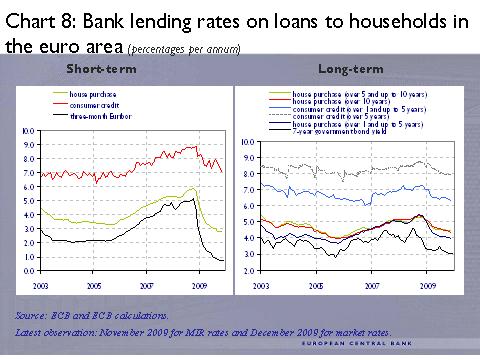

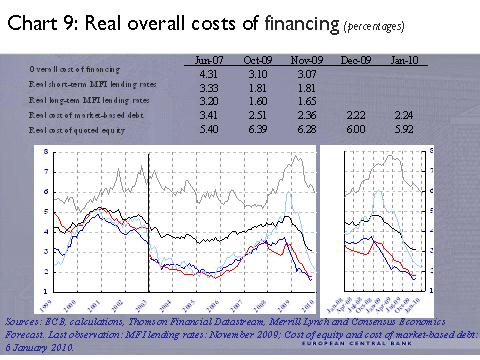

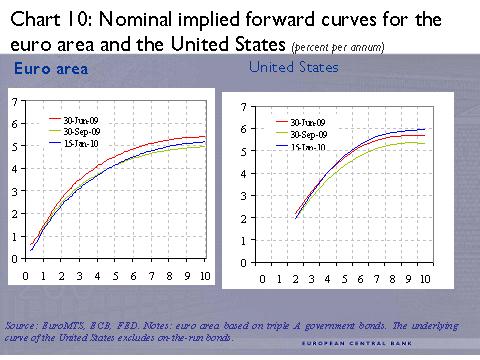

In order to promote understanding of how monetary policy needs to adapt to changing economic conditions, and eventually exit from its very accommodative stance, central banks would do well to explain how the stance itself is affected not only by the level of the interest rate they control, but also by the underlying economic developments, such as projected growth and inflation. In this respect, it is interesting to note that over the last six months, while economic activity and inflation have picked up, interest rates, both in nominal and real terms, have continued to fall. Spreads on different types of bond, except those of some governments, have continued to come down. The slope of the yield curve has slightly increased, in particular in the US (see Annex).

Finally, an exit is more easily communicated, and understood, by market participants if it is gradual. Any interest rate adjustment – even a slight one – entails some form of discontinuity, which may affect the whole yield curve. A credible gradual exit, if well communicated, minimises shocks to interest rate expectations. However, a gradual exit strategy is more likely to be credible if it is implemented in a timely way. If it gives the appearance of being late, the first step by the central bank is likely to cause a substantial revision of interest rate expectations and thus of the yield curve, strengthening the impact of the tightening.

To sum up, experience suggests that what matters most in any exit strategy is that markets are well prepared, so that when the decision is ultimately made they are not taken by surprise and suffer negative repercussions. Communicating an exit strategy is, in the end, not that different from communicating monetary policy in normal times. Given the state of uncertainty about the recovery, market participants have to base their expectations, and their trading decisions, on projected economic fundamentals rather than trying to read between the lines of policy announcements.

Annex

-

[1]Ben Bernanke, “Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble”, speech at the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, Atlanta, Georgia, 3 January 2010.

-

[2] Daniel Leigh, “Monetary Policy and the Lost: Decade: Lessons from Japan, IMF Working paper, October 2009.

-

[3]G. Eggertsson and B. Pugsley, “The mistake of 1937: a General Equilibrium Analysis”, CFS Working paper, November 2006.

-

[4] L. Bini Smaghi, “An Ocean Apart: Comparing Transatlantic Responses to the Financial Crisis”, Rome, September 2009.

-

[5]L. Bini Smaghi, “Monetary Policy and Asset Prices”, Freiburg, October 2009.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts