Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, April 2022

This is the second edition of the European Central Bank’s biennial report on financial integration and structure in the euro area. As explained in greater detail in the preface to the first edition in March 2020,[1] it is designed to focus on structural developments in the financial system of the euro area, and in some cases also of the European Union (EU), and related policy issues. In so doing, it covers developments in financial integration across member countries, changes in financial structure (the mixture of financial markets and intermediaries) and financial development or modernisation (for example through innovations in the financial system). Definitions of these three concepts and how they link to Eurosystem tasks and functions were provided in more detail in the 2020 preface.

The findings of this report may touch upon issues relevant for the policy discussion related to the European banking union (BU), the European capital markets union (CMU) and thereby on the financial aspects of deepening Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).

The report has been streamlined in two ways compared with the previous issue: by focusing on the main trends in financial integration, structure and development, and by replacing special feature articles with more concise boxes. The topics covered by the five boxes are the following:

- Making euro area equity markets fit for green and digital innovation;

- Measuring market-based and non-bank financing of non-financial corporations in the euro area;

- Frictions in debt issuance procedures and home bias in the euro area;

- Home bias in green bond markets;

- A deep dive into capital risk sharing in the euro area – inter- versus intra-regional risk sharing.

The standard set of indicators of financial integration and structure and their descriptions are included in an online Statistical Annex.

The report does not cover the implications of Russia’s military attack on Ukraine for the euro area or the EU financial system, as the data cut-off date was 11 February 2022.

Key messages

1 Overall assessment of financial structure and integration

The surveillance parts of this report cover developments in euro area financial structure, in terms of both financing instruments and financial intermediaries, as well as in euro area financial integration during the COVID pandemic period. The economic and financial implications of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the sizeable policy responses dominated most of the two-year reporting period of this report. There were, however, also a number of previous features and trends in financial structure and integration that continued or evolved differently during the last two years. The surveillance parts of the report – summarised in this section – describe the most important patterns in both regards. They consider aggregate and sectoral developments for different financing instruments (liability perspective) and for different financial intermediaries (notably from an asset perspective). They also review the integration of financial markets across member states and its resilience as well as assess risk sharing across member states.

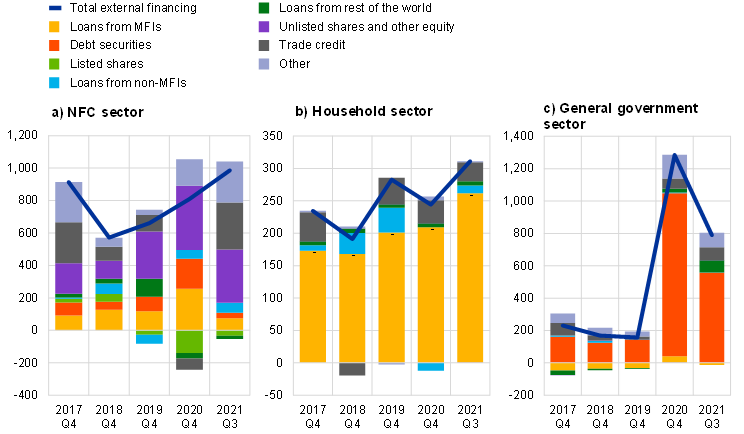

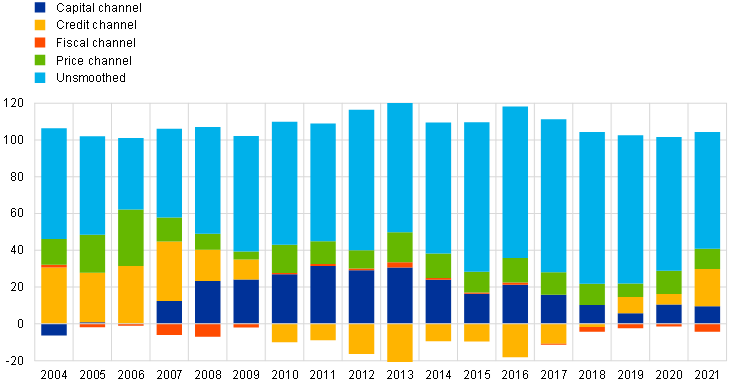

Thanks to a decisive set of policy responses the financing of euro area firms and households held up during the pandemic crisis, although this required a significant increase in public debt. As seen in Chart 1.1, aggregate external financing of both non-financial corporations (NFCs, left-hand panel) and households (middle panel) broadly held up in the euro area during the pandemic (blue lines in 2020 and 2021 compared to the years before). But this was only possible thanks to the fast and formidable policy support and actions that fiscal authorities, the Eurosystem and prudential authorities and bodies undertook in response to the pandemic. For example, the right-hand panel of Chart 1.1 visualises this in terms of the multiplication of public debt issuance necessary to finance measures supporting firms and households. The speed and decisiveness of the action clearly benefited from the experiences with the financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis a decade earlier and subsequent reforms.

Chart 1.1

External financing of euro area NFCs, households, and general governments by instrument

(flows; four-quarter sums; EUR billions, Q4 for 2017 -2020; Q3 for 2021)

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts) and ECB calculations.

Notes: MFI stands for Monetary and Financial Institutions. Non-MFIs include other financial institutions (OFIs) as well as insurance corporations and pension funds (ICPFs). "Other" is the difference between the total and the instruments included in the figure and includes inter-company loans and the rebalancing between non-financial and financial accounts data. Figures shown represent the sum of flows over the last four quarters at the end of Q4 for 2017 to 2020 and of Q3 for 2021.

In addition to fiscal support and guarantees, another factor helping non-financial corporations to stabilise was a fast change in their financing mix towards bank credit lines and corporate debt issuance, as also facilitated by various monetary policy measures. While total NFC financing held up overall, the pandemic triggered large swings in its composition. Notably, in 2020 trade credit and public equity issuance dried up (grey and green blocks in Chart 1.1), because of the great uncertainty about the viability of firms during lockdowns early in the crisis and a rush towards liquidity (“dash for cash”). At the same time, NFCs resorted more to debt financing, both through bank loans and through corporate debt securities (yellow and red blocks). Robustified by regulatory reforms decided after the Great Financial Crisis and supported by special ECB liquidity operations, banks were able to let firms draw elastically on their credit lines. In addition, much enhanced corporate bond purchases by the ECB through its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) made corporate issuance attractive.

Multiple support to companies was all the more important as the corporate sector could be regarded as the economic epicentre of the COVID crisis. The initially necessary social distancing and lockdowns very much limited the operations of firms in important sectors, constraining the employment of people earning wages, investment and the production, distribution and sale of goods and services. Therefore, the risks spread within the corporate sector and from there to supporting governments, financial intermediaries and consumers. One challenge for the future will be how the pandemic legacy of corporate debt will be resolved, including through the functioning of insolvency frameworks.

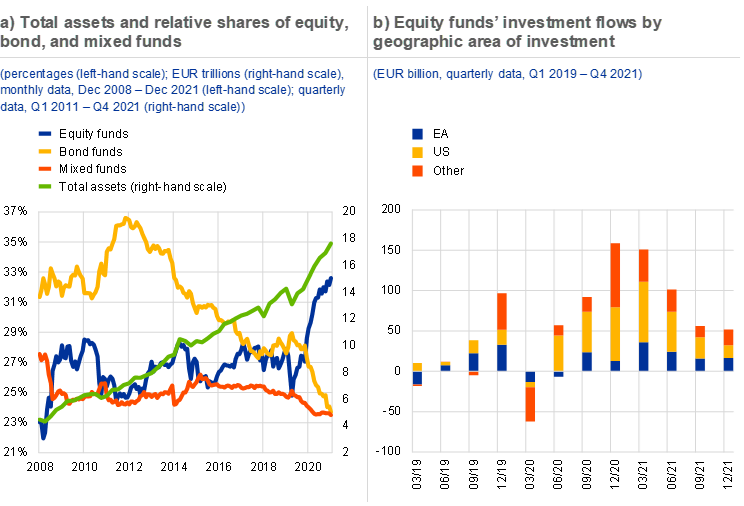

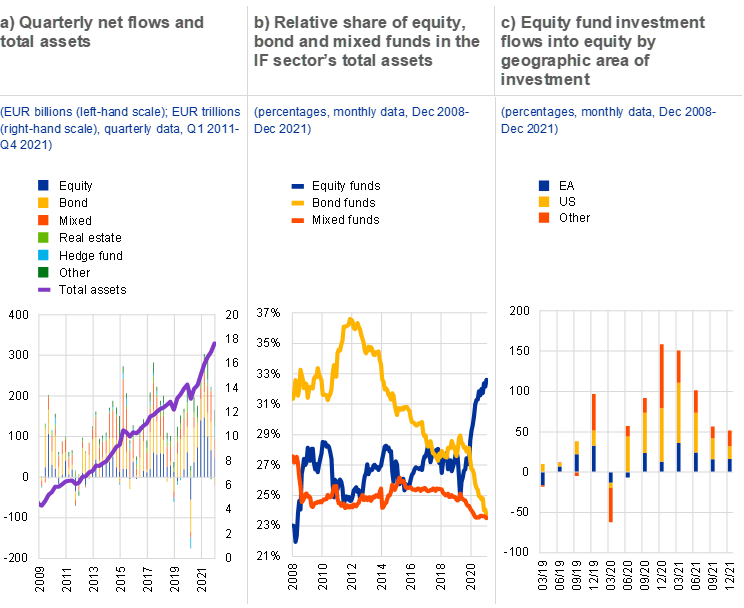

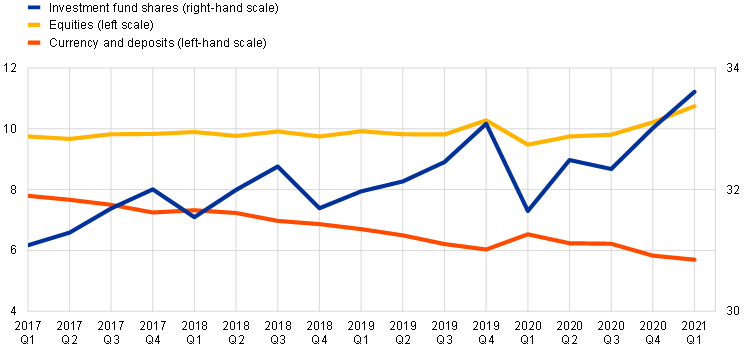

The trend towards non-bank financial intermediation continued, with an especially strong growth of investments funds, in particular for equity funds, despite some initial stresses in some segments of the fund sector. Turning from the perspective of financing instruments to the one of financial intermediaries, a trend that existed at least since the Great Financial Crisis is the growth of non-bank financial intermediaries in the euro area. For example, the share of non-banks in the provision of credit to NFCs grew from around 15 per cent at the time of the Great Financial Crisis to almost 30 per cent in 2021 (see panel b of Chart A in Box 2 of this report). A particularly strongly growing type of non-bank intermediary during the last two years were investment funds (green line in panel a of Chart 1.2), notably driven by equity funds (blue line). This reflected not only valuation effects on the back of strong fiscal support and monetary policy measures but also high inflows over a number of quarters. Apart from the low interest rate environment, the enhanced interest in portfolio equity investment may have been driven by the strong performance of stock markets until the cut-off date of this report. Finally, as of late also insurance corporations and pension funds increased their equity holdings, partly through the purchase of investment funds (Chart 9 in the main chapter of the report).

Chart 1.2

Developments in euro area investment funds

Sources: ECB (investment fund balance sheet statistics).

Notes: Panel b: "Other" refers to all equity transactions of euro area equity funds with counterpart area other than EA and US.

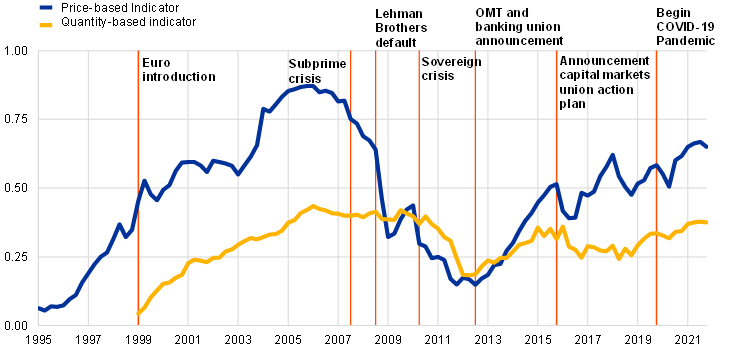

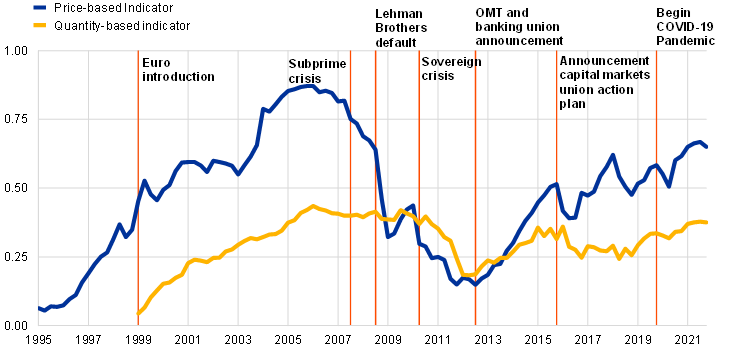

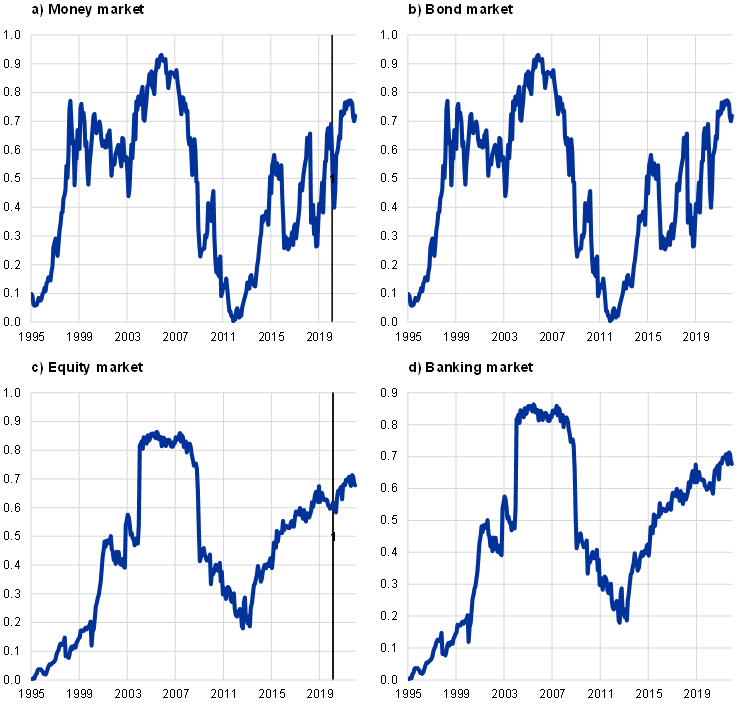

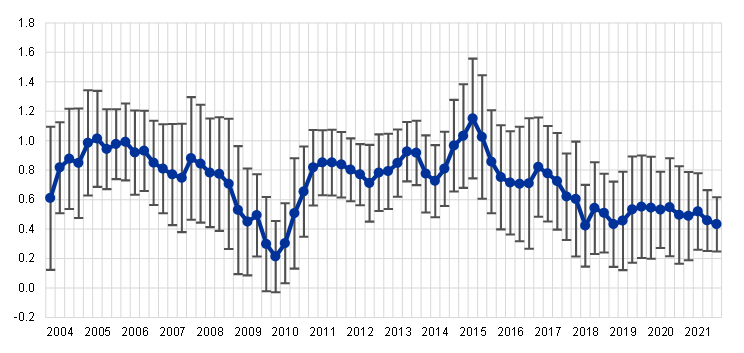

Contrary to previous major crises, a material decrease in euro area financial integration induced by the beginning of the pandemic – and more pronounced in prices than in quantities – stopped and reversed relatively quickly. Turning to euro area financial integration, Chart 1.3 shows the ECB’s two composite indicators that provide an aggregate picture of integration across the main market segments (money, bond, equity and banking markets) in terms of prices (blue line) and quantities (yellow line) since the start of the euro. The price-based indicator suggests that the moderated and volatile recovery of integration after the Great Financial Crisis and the European Sovereign Debt Crisis reported in the 2020 report was still intact until the cut-off date. Quantity-based integration (capturing cross-border bond holdings, equity holdings and interbank lending), however, moved broadly sideways for a number of years and only recovered somewhat more recently. The levels of integration measured with the latest data now compare to those of the mid-2000s, i.e. a few years before the financial crisis. Most importantly, the adverse effects of the COVID crisis on financial integration, while material in particular in terms of cross-border price divergences, seem to have been relatively short-lived both in prices and in quantities.

Chart 1.3

Price-based and quantity-based financial integration composite indicators

(quarterly data; price-based indicator: Q1 1995 – Q4 2021; quantity-based indicator: Q1 1999 – Q4 2021)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The price-based composite indicator aggregates ten indicators for money, bond, equity and retail banking markets, the quantity-based composite indicator aggregates five indicators for the same market segments except retail banking. The indicators are bounded between zero (full fragmentation) and one (full integration). Increases in the indicators signal greater financial integration. From January 2018 onwards the behaviour of the price-based indicator may have changed due to the transition from EONIA to €STR interest rates in the money market component. OMT stands for Outright Monetary Transactions. For a detailed description of the indicators and their input data, see the Statistical Web Annex to this report and Hoffmann, P., Kremer, M. and Zaharia, S. (2019), Financial integration in Europe through the lens of composite indicators, Working Paper Series, No 2319, ECB, September.

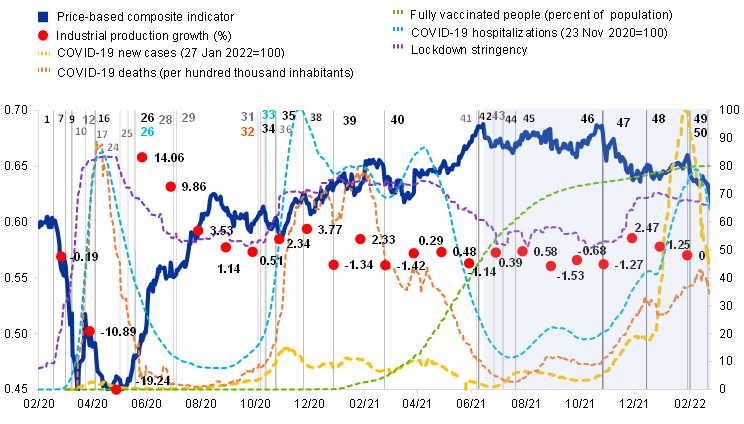

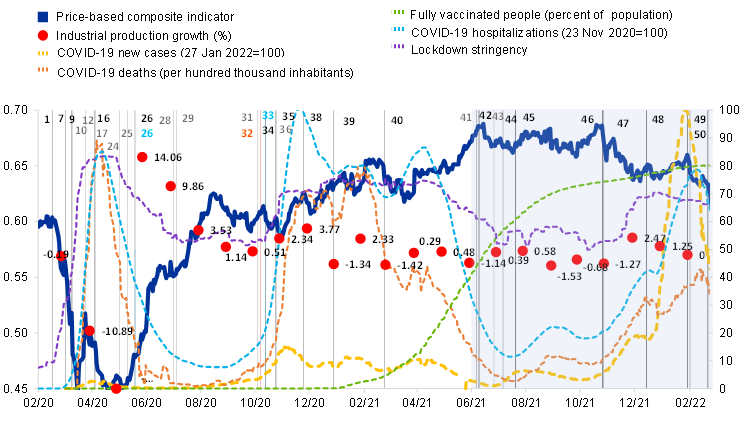

The most influential policy measures that first contained re-fragmentation in the euro area and then brought it back to pre-pandemic levels were first a prompt series of ECB monetary policy measures and then, decisively, the EU agreement about a very sizeable COVID recovery fund. To analyse in greater depth what happened with integration during the pandemic crisis, Chart 1.4 zooms in on the period February 2020 to February 2022. This is only possible with a high-frequency version of the price-based composite indicator (blue line), which is complemented with information about the severity of the crisis (various dashed lines), economic activity (red dots) and important events and policy actions (numbered and colour coded vertical lines). The chart first confirms the sharp re-fragmentation (and economic contraction) triggered by the first COVID wave and severe lockdown measures. Initial policy measures – including notably the ECB’s PEPP (e.g. events 7, 9 and 16) – were able to contain this development but not sustainably reverse it yet. Only when the two key proposals for a sizeable European recovery fund (events 24 and 25) combined with a number of other measures and developments a sustainable re-integration was set in motion. These other developments included particularly the previous adoption of three European safety nets for businesses, jobs and workers (event 17), the easing of the first virus wave (dashed orange and violet lines) and a sharp economic recovery. Thereafter, following also an expansion of the PEPP (event 26) and the European Council’s agreement on the NextGenerationEU recovery fund financed through the joint issuance of debt (events 28 and 29), the price-based composite ultimately reached pre-pandemic levels.

Chart 1.4

Euro area price-based financial integration, COVID-19 pandemic developments and events

(daily data, 3 February 2020 – 23 February 2022)

Sources: Price-based composite indicator and industrial production: ECB and ECB calculations; COVID-19 deaths, fully vaccinated people, and lockdown stringency index: Our World in Data.

Notes: The price-based composite indicator of financial integration is a high-frequency version (daily readings) of the one by Hoffmann et al. (2019), described in Borgioli et al. (2020). The indicator is calibrated to vary between 0 and 1. The COVID-19 deaths data series are measured as seven day moving averages. Fully vaccinated is the share relative total population. Industrial production growth (excluding construction) is measured as growth rate to the previous month. Lockdown stringency varies between 0 and 100 (100 = strictest) and is computed as an average of the COVID-19 stringency indexes of all euro area countries, weighted by their 2019 real GDP. It is based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans. PEPP stands for Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme and SURE for Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency. The chart distinguishes between four phases of the crisis, indicated by the grey and light blue shaded areas. The first captures the first infection wave, with drastic lockdowns and a severe economic downturn (mid-February to early May 2020). The second phase covers the stark economic rebound when infections had returned to low levels and member countries partly opened up again (early May to mid/late-August 2020). The third phase spans the severe return of infections in three more waves with, however, more targeted lockdowns and a more resilient economy than during the first phase (mid/late-August 2020 to end May 2021). The fourth phase is characterized by a combination of the rise in the number of COVID-19 new cases (including Delta and Omicron variants) together with the low number of deaths, high vaccination rates, and more resilience of financial integration (since June 2021 until February 2022).

Vertical lines and their numbers mark selected significant events (colours refer to country events – Italy red, Spain dark blue, Germany light blue – or events with euro area wide relevance – fiscal light brown, monetary policy and other black):

1. Closure of Italian schools and universities (4 March 2020), 7. ECB PEPP announcement (18 March), 9. PEPP legal documentation published (25 March 2020), 10. Third European Council with divergent views on coronabonds (26 March 2020), 12. Eurogroup agreement on comprehensive policy response (9 April 2020), 16. ECB collateral rating freeze (22 April), 17. Fourth European Council with endorsement of Eurogroup’s comprehensive policy response and plans for recovery fund (23 April), 24. Franco-German EUR 500 bn. European recovery fund proposal (18 May 2020), 25. European Commission EUR 750 bn. “NextGenerationEU” recovery instrument proposal (27 May 2020), 26./26. ECB PEPP expansion and Germany announces major fiscal stimulus package (4 June 2020), 28. Start of special European Council on recovery fund (17 July 2020), 29. End of special European Council on recovery fund with final agreement on size and structure (21 July 2020), 31. First issuance of EU Commission SURE bonds (21 October), 32. S&P upgraded the outlook on the Italian sovereign bond rating from negative to stable (23 October 2020), 33. Germany adopts toughest health restrictions since first lockdown (28 October 2020), 34. ECB hints at December monetary policy stimulus (29 October 2020), 35. BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine announcement (9 November 2020), 36.Second issuance of EU Commission SURE bonds (10 November 2020), 38. ECB expands PEPP envelope and announces to “preserve favourable financing conditions” (10 December 2020), 39. Announcement of US economic relief package (15 January 2021), 40. ECB temporarily increases PEPP purchases (11 March 2021), 41. Commission successfully placed 800 billion euros of bonds, "NextGenerationEU" (8 June 2021), 42. European Union countries agreed on an easing of travel restrictions over summer (11 June 2021), 43. EU hands out first payments from COVID-19 recovery fund, "NextGenerationEU" (28 June 2021), 44. ECB reformulates inflation goal to 2%, allows overshoot (8 July 2021), 45. ECB extends forward guidance on rates (22 July 2021), 46. ECB Governing Council (28 October 2021). 47. Inflation in the euro area is estimated at 4.1% in October (29 October 2021), 48. Governing Council meeting (16 December 2021), 49. Euro area GDP rose by 0.3% on quarter in the last three months of 2021, slightly less than predicted, after a sharp contraction in Germany's output (31 January 2022), 50. Governing Council follow up from December meeting announcing a gradual reduction of asset purchases and termination of PEPP net asset purchases (3 February 2022). Omitted numbers are relevant events suppressed for readability.

Once pre-pandemic levels were reached again, measured financial integration gradually further increased and remained resilient to further COVID waves. Following the establishment of the comprehensive set of national and European fiscal, monetary and prudential policy instruments, Chart 1.4 clearly shows how euro area financial integration remained resilient to the later waves of the coronavirus and its variants, as also national lockdown measures become less severe and eventually vaccinations picked up (dashed green line). If anything, integration further increased in the following quarters. The experience overall illustrates, among other things, how powerful aligned monetary and fiscal policies can be in stabilising financial markets specifically and the euro area more generally during a crisis.

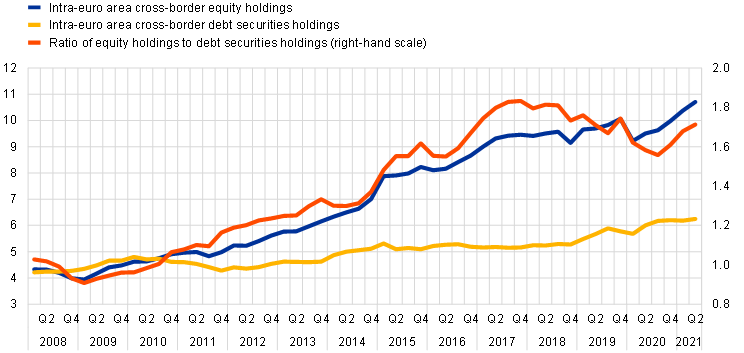

As flagged in the 2020 report, however, the resilience of integration to large shocks needs to be continuously monitored. For example, while the ratio of intra-euro area foreign equity investments relative to foreign debt investments has somewhat recovered during the pandemic (Chart 18 in the main chapter of the report), the ratio of intra-euro area foreign direct investment relative to combined FDI and portfolio equity investments continued to decline (Chart 19 in the main body). The former should increase the resilience of financial integration and the latter decrease it.

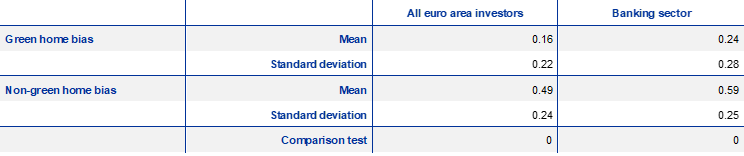

Measured quantity-based integration of the European Union green bond market may gradually decrease over time, from an initial high level, as all member states develop local bond supply and domestic investors have local alternatives (“home bias” effect). A particularly highly integrated European market is the relatively new market for green bonds. Box 4 of the report, however, finds that the limited investor home bias in this market (member countries’ investors holding a relatively large share of green bonds issued in other euro area countries) may have to do with the local underdevelopment of this market in some member countries. As soon as the domestic market develops and there is a greater local supply of green bonds, investors from these countries tend to reduce their foreign holdings to buy more domestically issued bonds and the green home bias increases, as a consequence. Although this process seems to be quite gradual, it may lead to a reduction of quantity-based integration measured in this market over time.

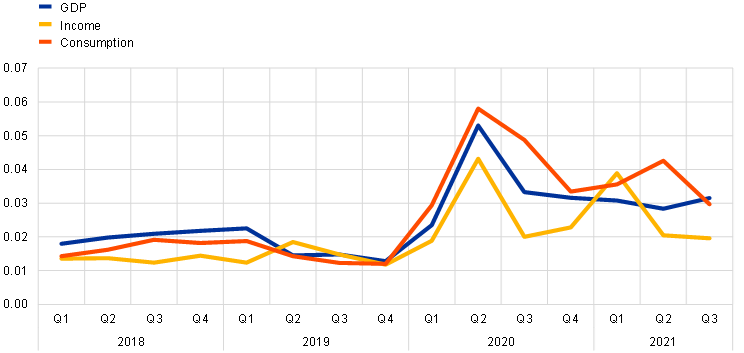

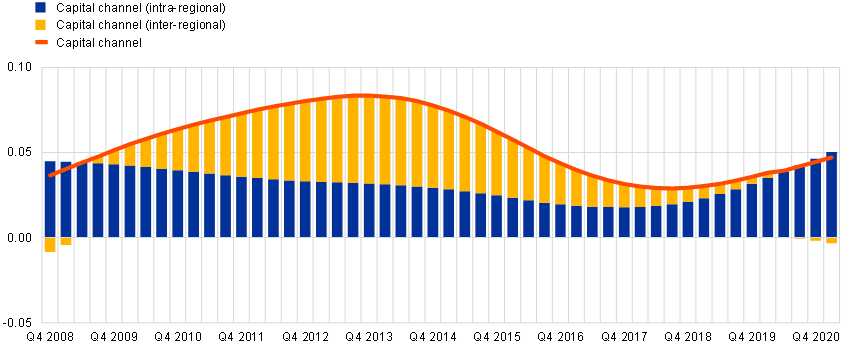

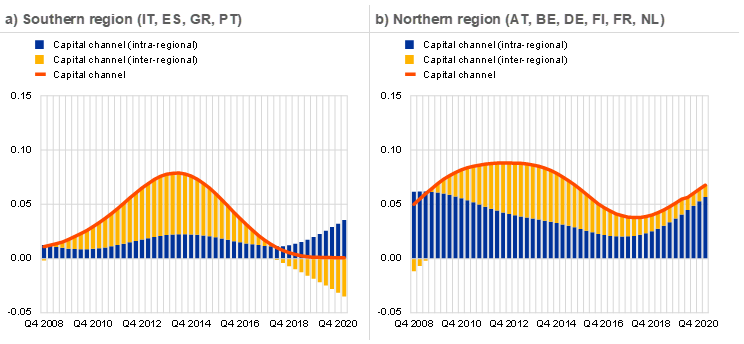

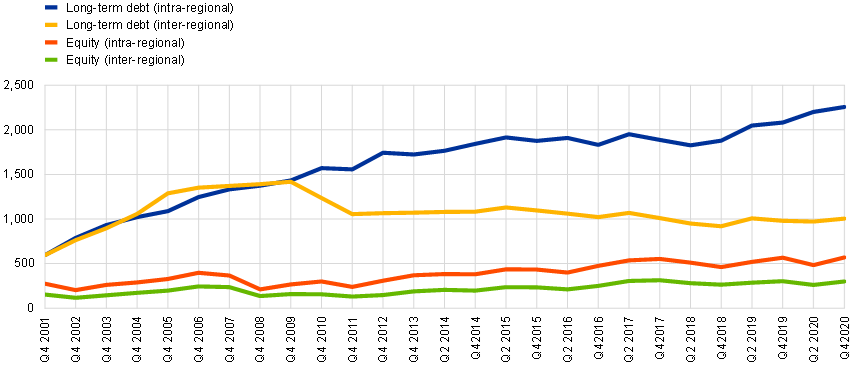

The nature of the COVID crisis very much restricted private consumption risk sharing across euro area countries, limiting one of the benefits of financial integration and development. An important economic benefit expected from financial integration and development in the euro area is risk sharing across member countries. The associated financial flows are expected to help households to better stabilise income and consumption in the face of shocks. While estimates suggest that income risk sharing has been relatively stable over the last years and the pandemic – in contrast to the Great Financial Crisis and the European Sovereign Debt Crisis –, it also remains at relatively low levels (Chart 23 in the main body of the report). At the same time, the nature of the COVID crisis restricted key private channels for consumption risk sharing, since public health measures, mobility restrictions and production constraints limited households in consuming their regular consumption baskets. Given the long data windows with which consumption risk sharing needs to be estimated, the measured moderate recovery – driven much by the credit channel but starting from a relatively low level – is still likely to be related to the resolution of the previous crises (Chart 24 in the main body). Box 5 of the report presents a historical analysis of the capital channel of risk sharing and confirms the relatively moderate contribution of this channel for the years following the European twin crises. Distinguishing a region of Northern euro area countries and a region of Southern euro area countries, it also finds that most of the capital channel operates within those regions rather than across them and that the inter-regional capital channel is particularly weak for the South.

The major fiscal initiatives at the EU level, such as the NextGenerationEU recovery programme and the three safety nets for business, jobs and workers, were key for ensuring risk sharing among member countries and for compensating for the hampered private financial channels. Given the nature and severity of the COVID crisis, it was therefore critical that the hampered private risk sharing channels were swiftly complemented with fiscal channels. This was all the more important, as the European Economic and Monetary Union does not include a fiscal union and therefore the fiscal risk sharing channel in the euro area is typically estimated as very small (Chart 24 in the main body). Sizeable fiscal risk sharing mechanisms were established with the three EU safety nets for businesses, jobs and workers and, notably, the NextGenerationEU pandemic recovery programme. From 2021 to 2026 NGEU can mobilise funds in the order of 6 per cent of EU GDP, with a significant annual volume of debt issuance at the European level. A large share of the NGEU grants and loans will be distributed to the countries most affected by the pandemic. Moreover, due to the joint backing of debt by all EU member states loans can be made available at favourable conditions. Pay-outs have started towards the end of 2021 and about a third of NGEU funds are expected to be used by the end of 2022. All this brings fiscal risk sharing in the EU to another level for a number of years, as the programme is designed to be temporary. But the success of the associated investments and reforms is expected to have a significant impact on the future debate on fiscal integration in the EU.

2 Selected policy issues for financial structure and integration

Completing the Banking Union and making material progress with the Capital Markets Union are key to enhance the integration and resilience of the financial sector and help Europe's post-COVID recovery. The description and assessments of financial integration and financial structure trends in the euro area and the EU in the previous section illustrate that there remain significant challenges ahead. Both as a consequence of the pandemic and as a consequence of otherwise existing trends. With the Banking Union (BU) and the Capital Markets Union (CMU) the EU has two interrelated projects under which many are already tackled, or new ones can be addressed going forward. A strong and integrated EU financial sector is essential to the EU’s post-recovery ambitions and requires a robust BU as well as an ambitiously deepened CMU, including in its green dimensions. The BU has come a long way since 2012, but further progress needs to be made on key missing elements, such as improving the crisis management framework or setting up a European deposit insurance scheme, and to ultimately complete the project. This would enable banks to conduct their business across the banking union without being hampered by national borders, allowing financing to reach the most promising projects. It would also make the banking sector more resilient. At the same time, the EU needs to urgently strengthen its financial markets beyond the banking segment. More developed and integrated capital markets would allow companies to diversify their funding sources, help mobilise investment across the Union and contribute to overall financial resilience, provided that the resilience of the non-bank financial sector is also strengthened so that it provides robust financing to companies in both normal and stressed market conditions.[2] Thus, the ECB welcomes the objectives of the European Commission’s second CMU action plan of September 2020 to achieve better access to finance for companies, make it safer for individuals to invest their savings and to better integrate EU capital markets. It supports the full and swift implementation of the envisaged reforms, including the proposals of November 2021[3] as well as outstanding actions such as on withholding tax and supervisory convergence. Alongside the advancement of the EU’s sustainable finance framework, these actions will also contribute to building a green CMU with sizeable, mature and integrated green capital markets.[4] The ECB also notes that more needs to be done to complete the single market for investment funds with more widespread cross-border distribution, because this promises to give investors more choice, reduce costs and fees, as recently also noted in a report by the European Court of Auditors (ECA).[5] Assessing the suitability of the regulatory framework, the ECA report highlights a lack of adequate and reliable data to mitigate risk to financial stability as a key concern and calls for strengthening ESMA’s role as a supervisor.

Selected areas discussed in the main body of this report that need enhanced policy efforts include equity markets, debt issuance procedures and bank consolidation. This section highlights a small number of policy considerations that emerge from the analysis presented in this report and go beyond the work already going on under the BU and CMU, at least in some dimensions. They touch on the role of more dynamic and integrated equity markets for financing European innovation, on better integrating European debt issuance procedures and on the need for further European bank consolidation.

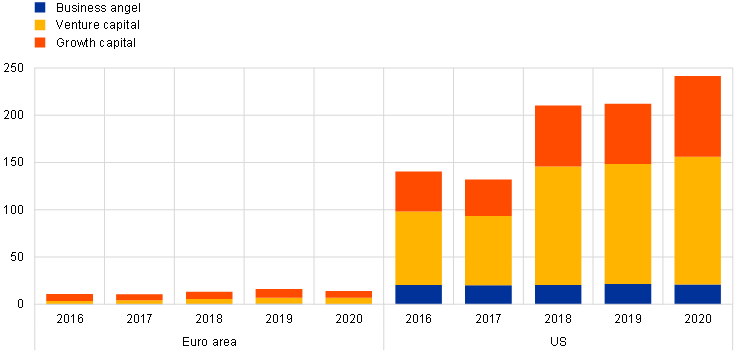

The NextGenerationEU recovery and public investment programme provides a unique historical opportunity to bring private risk capital markets in the euro area and EU to similar levels as is the case for other major economies. This way, private and public forces together ensure enough innovation and prepare the ground for financing the green, digital and other technological transformations. The green and digital transformations require sizeable investments for achieving the necessary technological and commercial innovations. If anything, the COVID pandemic and recent geopolitical events have further underlined the need to accelerate the EU’s twin transition. The European Commission has estimated that the average additional investment effort until 2030 to meet the EU’s current green and digital ambitions amounts to €650 billion per year across the EU. While public investments under NGEU and its significant share in green and digital investments will mean material progress, the required efforts will not be possible without also very substantial private investment. The research literature clearly suggests that public and private equity markets are much more suitable for providing the necessary funding for relatively risky innovation-orientation investment than bank lending. Yet, the relevant equity market segments in the euro area are significantly smaller and less integrated compared to other major advanced economies, even though European risk capital markets have grown well during the last few years.[6] For example, Chart 2.1 compares the size of risk capital markets in the euro area and the United States. A particular bottleneck seems to be the small size of European venture capital funds and a resulting lack of large funding rounds, which particularly hamper successful companies with high growth potential to scale up further. Moreover, public equity markets as the exit option for growing firms are also very much smaller in the euro area than in the US (Chart A, panel a) in Box 1 of the report).

The implementation of the 2020 CMU action plan can produce some tangible progress in the development and integration of European equity markets. As detailed in Box 1, For example, the creation of a European Single Access Point (ESAP), a digital platform for harmonised company information, including sustainability-related information and open to small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), as proposed by the Commission last November, can help to connect investors and companies. Moreover, the ongoing review of EU fund and insurance regulation envisages to facilitate institutional investors’ investments in green or other innovative projects. Additional measures under the Action Plan are forthcoming. The planned review of EU public listing rules should proceed swiftly to make listing easier for SMEs, including the set-up of an SME Initial Public Offering (IPO) fund. Moreover, the thorny path of making insolvency frameworks more efficient and more harmonised across member countries needs to be continued, as envisaged via a Commission proposal to be published later this year. This seems also important because of the greater indebtedness of many companies due to the COVID crisis and the possibility that currently low default rates may increase once fiscal support and public guarantees fully vanish.

Chart 2.1

Size and composition of risk capital markets in the euro area and United States

(EUR billion; annual data: 2016 2020)

Sources: European Business Angel Network (EBAN), Invest Europe, National Venture Capital Association (NVCA), Center for Venture Research (University of New Hampshire) for panel b.

Notes: The data covers data for all euro area countries excluding Cyprus, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia. Venture capital is a subset of private equity and refers to equity investments made for launch (seed), early development (start-up), or expansion (later stage venture) of business. “Seed” is funding provided before the investee company has started mass production/distribution with the aim to complete research, product definition or product design, also including market tests and creating prototypes. This funding will not be used to start mass production/distribution. “Start-up” is funding provided to companies, once the product or service is fully developed, to start mass production/distribution and to cover initial marketing. Companies may be in the process of being set up or may have been in business for a shorter time but have not sold their product commercially yet. The destination of the capital would be mostly to cover capital expenditures and initial working capital. “Later stage venture” is financing provided for an operating company, which may or may not be profitable. Late stage venture tends to be financing into companies already backed by VCs. For further details see www.investeurope.eu/research/. As for “Business Angel” investment these are (high-risk) investments made by private early stage investors typically in the form of seed financing towards startup businesses. Angel investment comprises financial contribution in addition to the investment of time, expertise and connections that the investors also provide in exchange for ownership equity in the startups.

Yet further actions will be necessary to build a vibrant EU equity ecosystem, notably to support European companies with high growth potential to scale up their activities. Greater efficiency and harmonisation of equity and venture capital frameworks across Member States, including addressing the debt-equity bias in taxation, could contribute to further grow and integrate the market. It is also worthwhile to consider how large companies can be further incentivised to provide corporate venture capital to start-ups.[7] Moreover, the extent of the currently ongoing technological transformations, the importance of risk capital for innovation and in turn the EU’s growth and competitiveness requires commensurate engagement of both the private and the public sector and the adequate balance between the two. For example, it may justify targeted public support to stimulate private investment in promising projects. The Scale-up Europe initiative launched by the French Presidency of the EU to achieve large pan-European equity funds for late-stage company financing is targeting precisely one key bottleneck in Europe’s capital market landscape. Obviously, the success of such initiatives also depends on effective policies in other fields outside the strict financial area, such as education, business-university clusters, competition, company and labour regulations, taxation and pension reforms.

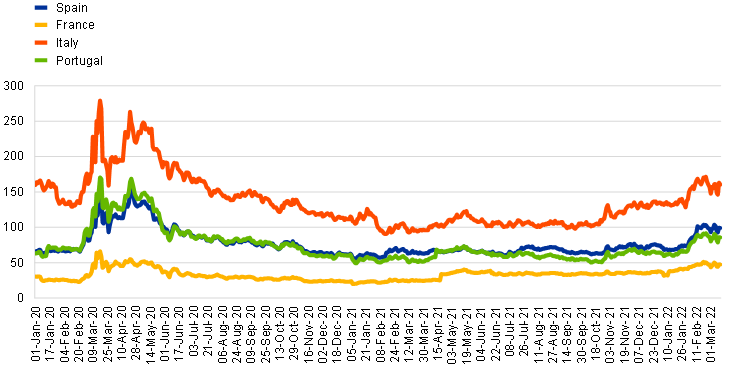

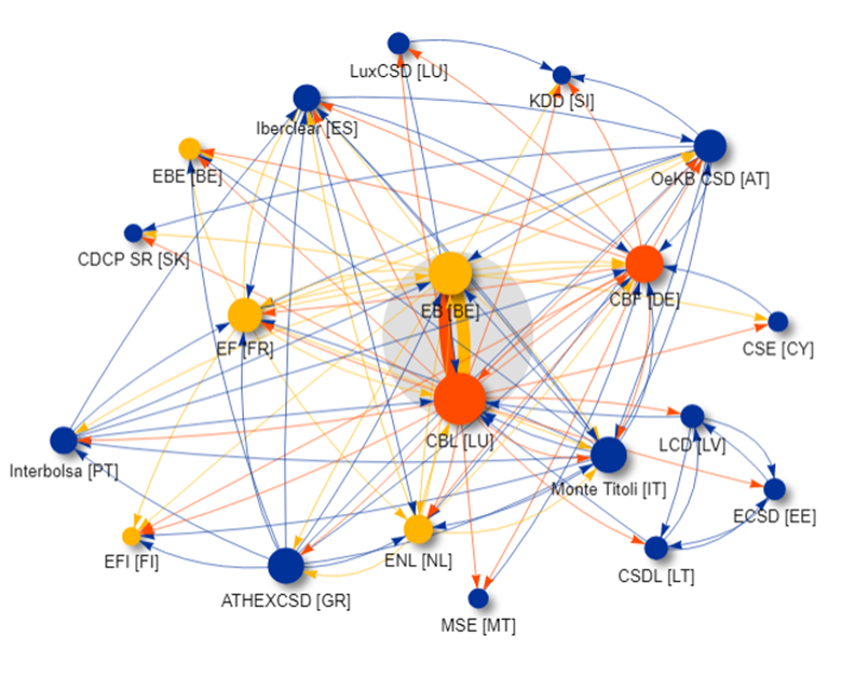

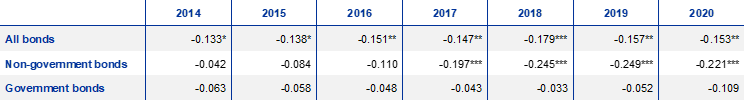

Debt issuance procedures need also to be better integrated and harmonised to reduce costs and allow investors to better diversify across EU countries. Turning to debt securities markets, there is no uniform issuance procedure at the moment. Box 3 of the report assesses to which extent home bias in debt securities holdings in the euro area could be reduced, if certain aspects of issuance processes were better integrated and therefore transaction costs reduced. The box focuses on links between Central Securities Depositories (CSDs), institutions mainly responsible for settlement and custody services and involved in the issuance process of new securities via their notary services. It finds that the existence of a link between two CSDs is associated with an economically and statistically significant reduction of home bias. It is therefore advisable to further integrate and harmonise debt issuance processes in the EU. Accordingly, the ECB supports initiatives under the September 2020 CMU action plan to reduce fragmentation in the European post-trade landscape and the SCoReE project (Single Collateral Management Rulebook for Europe).

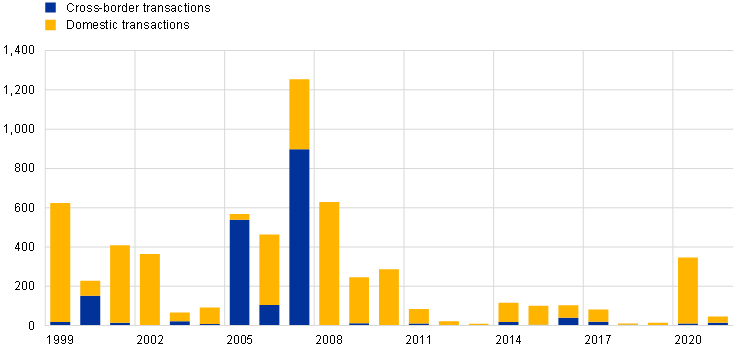

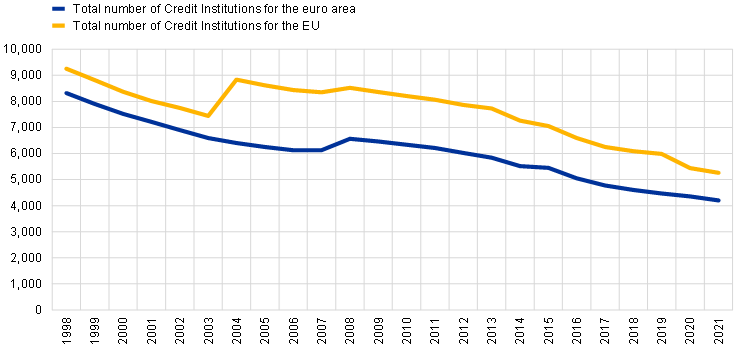

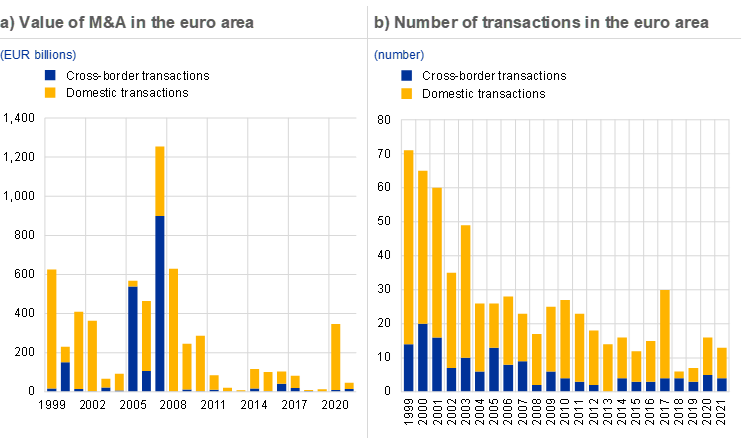

As further domestic and cross-border bank consolidation could help address structurally low profitability and fragmentation in retail credit markets, it should be considered to remove remaining regulatory obstacles. In what concerns EU credit institutions, further consolidation could reap several benefits. With a significant cross-border dimension, it could foster the integration of credit markets, diversify revenue sources and avoid concentrations at local level. Both domestic and cross-border bank mergers have the potential to address excess capacities and cost inefficiencies, two of the factors behind structurally low profitability in Europe. Chart 2.2 suggests that consolidation has been limited since the creation of the BU in 2012, despite some moderate pick up lately (see also Chart 7, left-hand panel, in the main body). While further consolidation should remain a market-driven process and be based on credible business plans ensuring institutions’ stability, ECB Banking Supervision supports addressing remaining regulatory obstacles to cross-border consolidation. For example, consolidation through branches rather than subsidiaries could imply a deeper and more cost-effective form of consolidation, but it may presently lead to a reallocation of risk across national Deposit Guarantee Schemes. The current Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive only allows the transfer of contributions for the last 12 months before a merger from the previously responsible scheme to the new one. A more balanced approach to the allocation of resources, in line with the opinion of the European Banking Authority on the issue, would limit risk shifting between the two schemes. In previous reports, the ECB has also made suggestions for the effective use of intragroup waivers to enhance the cross-border fungibility of capital and liquidity within banking groups.

Chart 2.2

Total assets of target banks in the euro area

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB calculations based on Dealogic and Orbis BankFocus.

Notes: The sample includes M&A transactions involving significant institutions and less significant institutions in the euro area, excluding some private transactions and transactions among small banks not reported in Dealogic. Transactions associated with the resolution of banks and distressed mergers were removed from the sample. Transactions are reported based on the year in which they were announced.

Structure and integration developments in the euro area financial system

We have recently witnessed an unprecedented shock, with non-financial corporations (NFCs) at its epicentre. The coronavirus brought a type of shock that was unprecedented in our lifetime, triggering a sharp economic downturn extraordinary in its speed, reach and scale across the world. The NFC sector was the economic epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, as a significant part of it was temporarily shut down or reduced in capacity. Risks then spread within the corporate sector – in the form of supply chain disruptions – and thereafter to bank and non-bank lenders. Despite its common origin, the economic and financial fallout from the crisis has been asymmetric across euro area countries: i.e. the effects on production, trade, investment, employment, consumption and financial systems have varied.

Financial structures and integration were severely stressed by the coronavirus crisis. A sequence of concerted monetary, fiscal and prudential policy responses were taken to mitigate the initial tendencies to financial fragmentation and avoid the financial sector aggravating the real-side impacts. As the period covered by this report (the last two years) coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic and financial implications of which started to materialise in Europe around mid-February 2020, particular emphasis is placed on how the ongoing crisis is influencing financial integration, structures and developments in the euro area.

The state of financial integration and the evolving structure of financial markets and intermediaries are two key elements for gauging the functioning of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). For example, they influence the extent to which asymmetric shocks can be shared and how the single monetary policy is transmitted across member countries.

This chapter is structured in two parts. The first investigates the structure of euro area financing markets and the provision of this financing by different euro area financial intermediaries. The second then focuses on measuring the extent of financial integration in the euro area, assessing the resilience of this integration and evaluating its implications for risk sharing.

1 Financial market structure

External financing of euro area NFCs and households (HHs) has held up since the onset of the pandemic (Chart 1, left-hand and middle panels, dark blue lines). It remained at levels broadly comparable with the pre-pandemic years, thanks to coordinated fiscal, monetary and prudential policy measures. NFCs and HHs financed themselves via debt instruments – loans, trade credits and debt securities – and equity instruments including listed and unlisted shares and other types of equities.[8] The timely and effective fiscal policy responses that stabilised markets and the economy came, however, at the cost of a significant increase in the financing needs of the general governments (GGs) (Chart 1, right-hand panel).

NFC external financing increased strongly at the start of the pandemic, and then slowed down from the second half of 2020. At the onset of the crisis, NFCs built precautionary liquidity buffers and front-loaded their financing needs via bank loans and debt securities,[9] as trade credit slowed down in the first half of 2020 on the back of much reduced economic activity.[10] The increase in external financing from the second half onwards was driven by improvements in trade credit and lending between NFCs, reflecting the recovery in economic activity and large firms’ liquidity support to their subsidiaries, sub-contractors and customers.

The economic contraction, combined with sharp declines in corporate sales and cash flows during the first months of the pandemic, drove up NFCs’ bank borrowing and net debt securities issuance in 2020 on the back of substantial monetary and fiscal policy support. As NFCs made a substantial effort to build up their cash buffers in 2020 and the larger ones replaced bank borrowing with market-based debt, their reliance on bank loans remained subdued in 2021. The debt increase in the euro area NFC sector was facilitated by the ECB stepping up its corporate bond purchases, as part of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). The TLTRO-III also had a positive impact on bank lending to firms.

Net issuance of listed NFC shares was negative in 2020, only returning to positive levels in 2021. At the same time net issuance of unlisted shares increased markedly. Net issuance of listed NFC shares in 2020 was strongly and negatively affected by a shift from listed equites to unlisted, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and balance sheet restructuring by multinationals. In addition to the impact of de-listing, net issuance of unlisted shares was supported by the recovery in the creation of new firms and possible recapitalisation needs of existing businesses. The renewed increase in net listed shares in 2021 was driven by robust issuance in the technology sector, moderate recapitalisations by unlisted firms and improvements in new listings.[11]

Household financing flows remained at pre-pandemic levels all along. Fiscal support measures for households, high household saving ratios and continued credit growth on the back of lending for house purchases sustained household financing.

Government financing increased strongly in 2020 before the economic recovery in the latter part of 2020 and 2021, coupled with progress on the health crisis, partly reversed the drivers of this trend. The sharp contraction in economic activity in the first half of 2020 led to a sudden drop in tax revenues and a surge in current expenditures (due to automatic stabilisers and increased subsidies and transfer payments). While government consumption and investment increased from late 2020, government income also grew substantially as tax collection rose and the fiscal support measures for households put in place to mitigate the crisis declined.

Chart 1

External financing of euro area NFCs, households and general governments by instrument

(flows; four-quarter sums; EUR billions, Q4 for 2017-2020; Q3 for 2021)

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts) and ECB calculations.

Notes: MFI stands for Monetary and Financial Institutions. Non-MFIs include other financial institutions (OFIs) as well as insurance corporations and pension funds (ICPFs). "Other" is the difference between the total and the instruments included in the figure and includes inter-company loans and the rebalancing between non-financial and financial accounts data. Figures shown represent the sum of flows over the last four quarters at the end of Q4 for 2017 to 2020 and of Q3 for 2021.

For all sectors, the COVID-19 crisis increased the outstanding amount of total financing relative to euro area GDP. It also moderately altered the composition of the euro area economy’s balance sheet liabilities (Chart 2). The amount of total financing grew, both as a result of increased volumes and higher valuations. At the end of the third quarter of 2021, aggregate financing amounted to €73.8 trillion, or 6.1 times nominal GDP (Chart 2, middle panel).[12] The strong net issuance of debt securities since end-2019 has extended the euro area economy’s reliance on debt financing and increased the use of marketable instruments in the euro area economy’s financing mix. Debt instruments and marketable instruments increased their relative share in the financing mix by 1.1 percentage points and 0.6 percentage points respectively, mostly on account of the large government debt increase. Euro area GDP also declined considerably in 2020.

Chart 2

External financing of euro area economy

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts) and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart is constructed from the liabilities of all economic sectors, excluding liabilities to the rest of the world, loans from NFCs (to net out intra-company loans in this non-consolidated data), currency and deposits, investment fund shares or units, entitlements from pension, insurance and standardised guarantee schemes, financial derivatives and employee stock options as well as other accounts payable. Other equity refers to equity claims that are not securities listed on an exchange and not unlisted securities, such as equity in incorporated partnerships, equity in limited liability companies whose owners are partners, capital invested in cooperative societies or investment by the government in the capital of public corporations whose capital is not divided into shares. The European System of Accounts (ESA) 2010 underlying the euro area data is broadly consistent with the SNA 2008, although in some cases it may be more detailed.

The figures for 2021 include values up to Q3, due to data availability.

An overarching lesson is that post-pandemic financing needs call for deeper and more dynamic capital markets, in particular equity markets, as well as the mobilisation of additional capital.[13] The euro area NFC sector in particular will need to re-balance debt/equity ratios to address the post-pandemic debt overhang by reallocating capital from debt to equity or mobilising additional risk capital to support growth and innovation in the euro area economy. A case in point is the depth and integration of the rapidly growing sustainable financing segment (see Box 1: Making euro area equity markets fit for green and digital innovation). Euro area economic agents will most importantly need to cater for investment efforts to meet the challenges of greening and digitising the euro area economy. At the EU level, these are estimated at €650 billion per year up to 2030.[14] This annual investment effort represents 5.4% of euro area GDP, 31.2% of combined euro area NFC, HH and GG financing and 2.3% of euro area household deposits (four quarter sum figures at the end of the third quarter of 2021).

The euro area financial sector’s capacity to attract and intermediate funds to euro area economic agents will crucially depend on scaling up market-based financing and an increasing role for the non-bank financial sector. The ECB regularly assesses these issues (see Sections 3.1 and 3.2) and tracks progress (see Box 2: Measuring market-based and non-bank financing).

Box 1

Making euro area equity markets fit for green and digital innovation

Capital markets, and equity financing in particular, will be essential to meet the EU’s post-recovery ambitions. The investment required to green and digitalise the EU economy is estimated at €650 billion per year until 2030, far exceeding public recovery spending.[15] Alongside public investment programmes such as NextGenerationEU, which are expected to considerably boost innovative sectors and companies, private investment will have to be stepped up significantly over the coming years. This would help meet programme objectives and leverage the innovation and transformation potential, especially as public programmes expire.[16] From a financing perspective, research shows that equity is more suitable for riskier and innovative projects than debt.[17] Equity financing can also have a stabilising impact in an environment in which the COVID-19 crisis has increased corporate leverage substantially. Equity will thus be vital in closing the investment gap and financing post-recovery economic activity. This box provides an overview of euro area equity markets by type of equity and investor and highlights the need to further improve Europe’s equity landscape, in particular as regards risk capital.

Equity financing plays a central role in funding innovation, and is therefore a crucial complement to public investment in delivering the green and digital transition.[18] In contrast to bank lenders, equity investors are more willing to assume the greater risks associated with innovation and do not require tangible collateral.[19] The equity share of an economy (equity as a share of the sum of equity and credit) has been shown to positively correlate with green innovation.[20] Venture capital investments specifically have also been shown to spur innovation,[21] including green innovation, and there is evidence that their social return is significantly greater that of public or business R&D.[22] Accordingly, economies with a greater share of public and private equity in their financial structure have been found to de-carbonise faster than those that are more debt and bank-based.[23] At the same time, innovation is an economy-wide effort, and the extent and speed of innovation required for the green and digital transformations will also depend on public-sector initiatives and synergies between different sectors. In particular, large “mission-oriented” investment programmes induce material spillovers between the many different private and public actors involved and frequently result in innovation.[24] More generally, funding availability plays a key role throughout the R&D process, including the dissemination of new technologies; this illustrates the point that public spending on R&D and private risk capital complement each other in fostering green and digital innovation.

An enabling equity ecosystem for innovative companies includes venture capital and access to public equity markets[25]. While only 0.5% of US firms are backed by venture capital, these account for nearly half of all public listings.[26] Venture capital, especially by corporates, is also typically accompanied by significant know-how transfer. Survey data show that initial public offerings (IPOs) are a key exit strategy for firms backed by venture capital.[27] This not only highlights the role of venture capital, but also the importance of a diversified choice of equity instruments to help firms grow to scale and reach their full potential.[28]

Chart A

A comparison of the euro area and the US: equity financing requirements by type of equity

(ratio to nominal GDP (left-hand panel); EUR billion (right-hand panel); annual data: 2016-2020)

Sources: Panel a: ECB and OECD; panel b: European Business Angel Network, Invest Europe, National Venture Capital Association, Center for Venture Research (University of New Hampshire).

Notes: Panel a: the chart is based on financial accounts data. Other equity refers to equity claims that are not securities listed on an exchange and not unlisted securities, such as equity in incorporated partnerships, equity in limited liability companies whose owners are partners, capital invested in cooperative societies or investment by the government in the capital of public corporations whose capital is not divided into shares. Data for the US are based on the global System of National Accounts 2008. The European System of Accounts 2010 underlying the euro area data is broadly consistent with the SNA 2008, although in some cases it may be more detailed; panel b: the data cover all euro area countries except Cyprus, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia. Venture capital is a subset of private equity and refers to equity investments made for launch (seed), early development (start-up), or expansion (later stage venture). “Seed” is funding provided before the investee company has started mass production/distribution, with the aim of completing research or defining and designing the product, including market testing and creating prototypes. This funding is not used to start mass production/distribution. “Start-up” is funding provided to companies once the product or service is fully developed, to start mass production/distribution and cover initial marketing. Companies may be in the process of being set up or may have been in business for a shorter time, but have not sold their product commercially yet. The use of the capital would mostly be to cover capital expenditure and initial working capital. “Later stage venture” is financing provided for an operating company, which may or may not be profitable. This tends to be financing provided to companies already backed by VCs. For further details see www.investeurope.eu/research/. “Business Angel” investments are (high-risk) investments made by early-stage private investors, typically in the form of seed financing for start-up businesses. Angel investments comprise both financial contributions and time, expertise and connections the investors provide in exchange for ownership equity.

European private equity and risk capital have grown in recent years, but the euro area still lags behind international peers. While aggregate euro area equity markets have stagnated in size over recent years, private equity has gained in relative importance compared to public equity. This is in stark contrast to the US, where listed equity plays a dominant role (see Chart A, left-hand panel). Total euro area early-stage equity financing (or risk capital) – including business angel, venture capital and growth equity investments – grew from €10.7bn in 2016 to just short of €14bn in 2020, with venture capital accounting for nearly all of the increase. Yet, despite euro area venture capital having doubled over this period, the gap with the US widened: it is now less than 5 percent of US venture capital. Similarly, total euro area risk capital is less than one-tenth of US risk capital (see Chart A, right-hand panel). The structure of venture capital financing also differs compared to the US, with most euro area venture capital funds concentrated on comparatively small, early-stage funding for companies.[29] This later-stage funding gap has been reported to lead high-growth high-potential companies (“scale-ups”) to seek funding from abroad in the pre-IPO phase; this can even lead to these companies relocating their operations.[30] US venture capital funds, for instance, are on average three times larger than their European counterparts and, in terms of capital raised between 2010 to 2019, the biggest EU venture capital firm is three times smaller than the 10th largest US venture capital firm.[31] Finally, there are also significant differences in the size of risk capital markets across euro area countries.

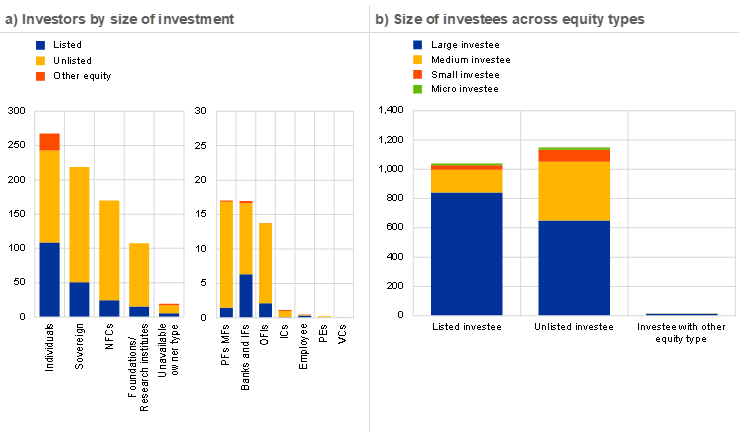

Knowledge of the main providers of equity financing to euro area NFCs can help assess the size of the equity financing gap in the euro area and identify ways to narrow it. To further shed light on the providers of equity financing to euro area non-financial corporations (NFCs), the following analysis uses 2020 Bureau van Dijk ORBIS data.[32] The sample underlying this analysis covers 8,706 euro area NFCs with 7,810 distinct ultimate owners (i.e. investors) and aggregated equity capital at book value amounting to EUR 2.7 trillion. 5,263 NFCs in the sample can be clearly assigned to the following three key economic sectors: manufacturing (40% of the sample’s equity: 2,104 entities representing 24% of the total number of entities); professional, scientific and technical activities (13% and 23% respectively); and wholesale and retail trade (4% and 13% respectively).[33]

Individuals and sovereigns are the main providers of equity funding for NFCs (Chart B, left-hand panel). Individuals provide 50%, 23% and 87% of listed, unlisted and other[34] equity financing respectively. Sovereigns are the main providers of unlisted equity financing (29% of total unlisted equity) and the second largest provider of listed equity financing (24% of total listed equity). Sovereign investors – led by Italy (27% of total sovereign investment), France (23%), Germany (21%) and Austria (13%) – invest principally in large-sized companies. Financial corporations[35] (including investment companies and other financial intermediaries) supply 6% of euro area NFCs’ equity financing, with investment companies and other financial intermediaries (OFIs)[36] providing 2%. The role of OFIs reflects the provision of intra-NFC equity financing e.g. via captive finance companies. Foundations and research institutes represent 13% of total equity financing.[37]

NFCs are also important providers of listed and unlisted equity financing. They see this as a way of implementing their business strategies and investing in early stage companies. Empirical evidence shows that NFCs which have benefitted from venture capital financing are more likely to provide venture capital financing to others,[38] thereby strengthening the corporate venture capital ecosystem. NFCs compete in this role with private equity funds (PEs), venture capitalists (VCs) and other early-stage risk capital providers. The methodological approach adopted for this analysis[39] underestimates the role of PEs and VCs companies for euro area NFC equity financing. VCs and PEs tend to own NFC equity via structures such as funds of funds, which are not covered in Chart B, rather than as direct portfolio positions.[40]

It is chiefly large and medium-sized euro area NFCs that issue listed equity (Chart B, right-hand panel). The challenges small companies face to list on public markets include the fixed costs of listings, the lower liquidity of small stocks and the limited incentives for the advisory ecosystem to support SMEs looking to hold an IPO.[41]

Chart B

Equity investments by investor sector and composition of equity investments by investee size

(2020; EUR billions (left-hand panel); number of NFCs (right-hand panel))

Source: Bureau van Dijk ORBIS database and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart reflects the size of the investment of ultimate owners holding more than 25%. Size of investment consists of shareholders’ equity at book value provided by each investor to euro area consolidated NFCs in the sample. Consistent with the definition of “Other equity F.519” in ESA 2010, this includes the equity of partnerships, cooperative companies, branches, and foreign companies. Left-hand panel: banks and other investment companies are identified within the same category of investors by Orbis. Individuals are single private shareholders and shareholders designated by more than one named individual or family. NFCs are non-financial companies. Sovereign are states, governmental agencies, governmental departments and local authorities. OFIs are other financial intermediaries not classified as IBs and MFIs (broad category of monetary financial institutions and investment companies), PFs and MFs (pension funds and mutual funds), ICs (insurance corporations), PEs (private equity funds), HFs (hedge funds) or VCs (venture capital funds). Right-hand panel: the size of investees is consistent with the definition of SMEs provided by the European Commission. Medium entities have total assets of less than €43 million and the number of employees is less than or equal to 250. Small entities have total assets of less than €10 million and the number of employees is less than or equal to 50. Micro entities have total assets of less than €2 million and the number of employees is less than or equal to 10.

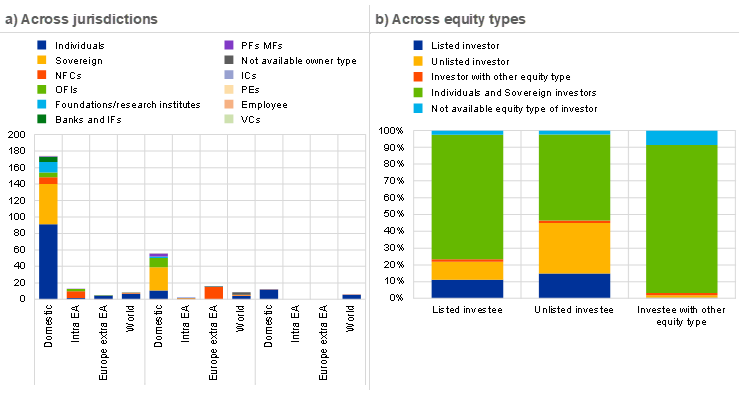

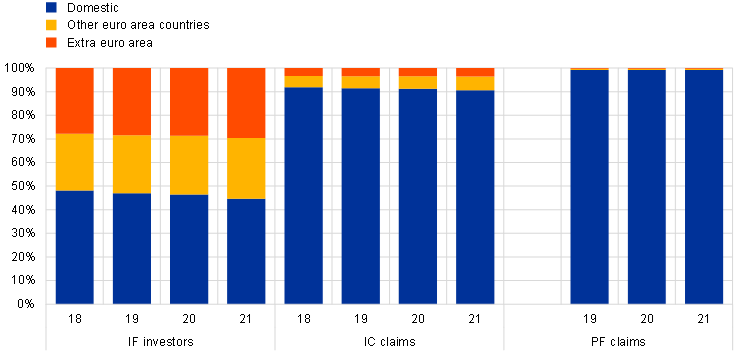

A pronounced home bias prevails across all types of equity financing (Chart C, left-hand panel). Equity investors from outside the euro area play a relatively more important role in providing equity financing in the form of unlisted or other equity to euro area NFCs. Looking at the residence of investors or investing firms, cross-border equity financing within the euro area is very low across all equity types and points to fragmented euro area equity markets. The strong role of individuals and the domestic public sector explain this home bias.

Excluding equity investments by individuals and sovereigns, equity is channelled from listed firms to unlisted ones (Chart C, right-hand panel). Sovereign and individuals can take stakes directly in listed equity or indirectly via investment vehicles.[42] Banks and asset managers enable retail or wholesale investors to participate in equity financing predominantly through fund structures.

Chart C

Equity financing funnelled across jurisdictions and equity types

(2020; EUR billions (left-hand panel); percentages (right-hand panel))

Source: Bureau van Dijk ORBIS database and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart reflects the size of the investment of ultimate owners holding more than 25%. Size of investment consists of shareholders’ equity at book value provided by each investor to euro area consolidated NFCs in the sample. Banks and other investment companies are identified within the same category of investors by Orbis. Individuals are single private shareholders and shareholders designated by more than one named individual or family. NFCs are non-financial companies. Sovereigns are states, governmental agencies, governmental departments, and local authorities. OFIs are other financial corporations not classified as IBs and MFIs (broad category of monetary financial institutions and investment companies), PFs and MFs (pension funds and mutual funds), ICs (insurance corporations), PEs (private equity funds), HFs (hedge funds) or VCs (venture capital funds). Left-hand panel: the category “Europe extra euro area” refers to every European country, including countries outside the EU. Consistent with the definition of “Other equity F.519” in ESA 2010, this includes the equity of partnerships, cooperative companies, branches, and foreign companies. Right-hand panel: Percentages are computed as the equity provided by the investors as a share of total equity provided by all investors included in our data source.

The insights from this analysis suggest a need to further develop EU equity markets, especially with a view to strengthening funding opportunities for smaller, greener or innovative companies. Some measures to facilitate companies’ access to different types of funding are already under way or have been announced, in line with the European Commission’s 2020 Capital Markets Union Action Plan.[43] The recent proposal by the European Commission to create a digital platform providing free and centralised access to EU company and investment product information – the European Single Access Point (ESAP) – should make it easier for investors to identify investment opportunities and for companies to raise funding, both on private and public markets. It is especially welcome that the ESAP will include sustainability-related information, which can help gear funding toward greener activities, and be open to SMEs. Similarly, the forthcoming review of EU public listing rules by the European Commission, which will aim to make listing easier for SMEs, not least by setting up a dedicated SME IPO fund, is an opportunity to diversify smaller companies’ access to equity funding.

However, additional measures are necessary to grow the investor base and close the equity funding gap with international peers, especially in risk capital markets. Facilitating investments by institutional investors in green and innovative projects, as for instance envisaged in the ongoing review of EU fund and insurance regulation, is an important element to this effect. However, more fundamental reforms will be necessary to help Europe move closer towards its international peers as regards risk capital and cater to the needs of a highly innovative and competitive economy. More efficient and harmonised insolvency laws and regulatory frameworks for equity investments, including addressing the debt-equity bias in taxation, can improve certainty for investors, reduce costs and facilitate cross-border investments, while also making risk capital more attractive and accessible to companies.[44] Other reforms could include incentives for large companies to provide corporate venture capital for start-ups. Given the gap against international peers and the positive spillovers from cross-sectoral cooperation in innovation, there appears to be a strong case for expanding public initiatives to help catalyse risk capital investments, notably via promotional banks. Recent initiatives such as the European Innovation Council (under the EU budget) or the public-private Scale-up Europe initiative to support the creation of large pan-European equity funds for late-stage company financing provide a welcome boost. Jointly, these measures – together with an ambitious implementation of the CMU Action Plan more broadly – will contribute to building a more dynamic funding ecosystem with positive spillovers for innovation. As such, they are also an important element for building a green CMU with sizeable, mature and integrated green capital markets.[45] In turn, these measures will facilitate the transition to a greener and more digitised economy and the success of public investment programmes, while promoting the EU’s strategic autonomy.

2 Financial intermediary structure

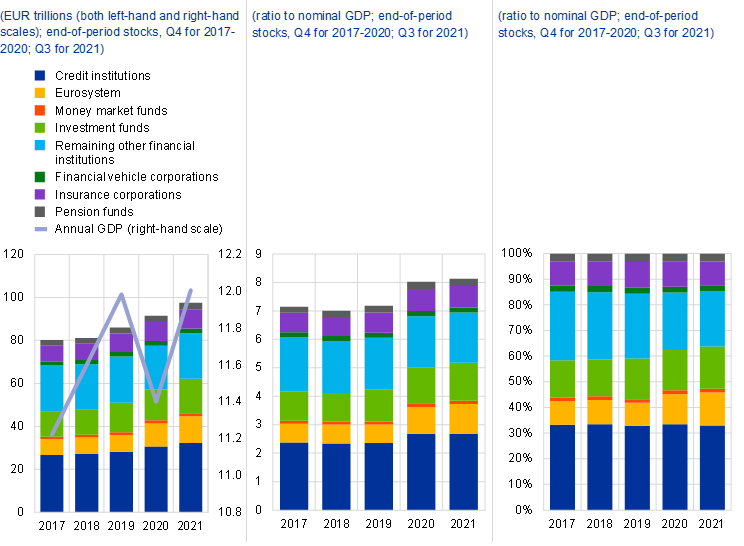

The growth of the euro area financial system since 2019 has come on the back of a strong increase in financial assets held by credit institutions and investment funds (Chart 3). Overall financial system assets have grown by €11.5 trillion since end-2019, with Eurosystem assets contributing €4.9 trillion of this. Valuation effects were a main driver of the increase in total financial sector assets (Chart 3, left-hand panel) together with increased ECB asset purchases through the PEPP.

Of the various financial sub-sectors, banks and investment funds have recorded the strongest increase in their financial assets over the last two years. Banks’ total assets grew by €3.9 trillion, predominantly thanks to fiscal, monetary and prudential policy support allowing them to provide credit flexibly. Investment funds benefitted from strong inflows and valuation effects that increased their financial assets by €2.4 trillion.[46] Other financial institutions (OFIs) – mainly holding companies and funding vehicles channelling funding flows in corporate groups – was the only sub-sector that saw financial assets decrease (-€0.5 trillion).

Financial system assets now represent eight times nominal GDP. The sharp economic contraction in 2020 (the grey line in Chart 3, left-hand panel) coupled with an increase in the volume and value of financial sector assets, pushed the ratio of total financial system assets to GDP from 7.2 in 2019 to 8.0 in 2020. This increased further to 8.1 in 2021 as the volume and value of financial sector assets increased, but by less than nominal GDP, which returned to its 2019 level (Chart 3, middle panel).

Chart 3

Total assets of the euro area financial sector

Source: ECB.

Notes: The aggregated (non-consolidated) assets of sub-sectors include financial assets and exclude non-financial assets. Remaining other financial institutions include security and derivative dealers, financial corporations engaged in lending (such as leasing or factoring companies), specialised financial corporations (including venture capital companies, export/import financing companies and some central clearing counterparties), financial auxiliaries (including asset management companies, securities brokers, investment advisers, insurance brokers and exchanges) plus captive financial institutions and money lenders (including financial holding companies, funding vehicles of non-financial corporations – e.g. supporting their debt issuance – and other entities that channel financial flows within non-financial corporations).

Changes in the euro area financial structure highlight a softening of bank dominance and the increasing weight of investment funds (Chart 3, right-hand panel). In relative terms, investment funds further increased their role (up by 0.6 percentage points compared to 2019) and the share of credit institutions grew slightly (by 0.1 percentage points), whereas all other sub-sectors saw their weight decrease, specifically OFIs (down by 3.5 percentage points).

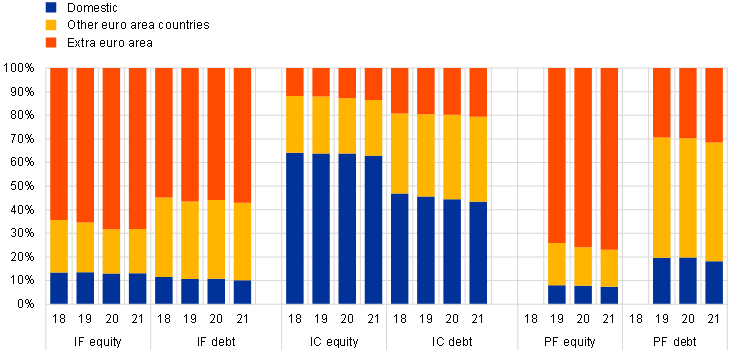

The non-bank sector has continued to gain importance for euro area real economy financing. Non-bank financial intermediaries – more narrowly defined as money market funds (MMFs), investment funds (IFs), insurance corporations (ICs), pension funds (PFs) and financial vehicle corporations (FVCs) – held a combined €31.7 trillion in financial assets by end-2021 and accounted for 37.3% of the total financial sector.[47]

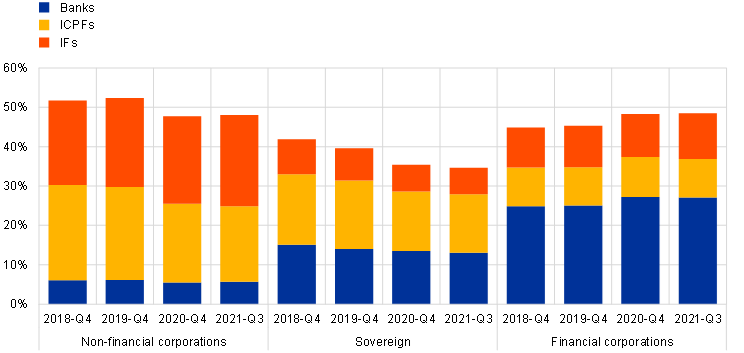

The non-bank sector has grown continuously over recent years and provides a significant share of total funding to the euro area real economy. IFs and ICPFs hold more than 40% of outstanding euro area NFC market debt (Chart 4) and bought the lion’s share of the record-high new issuance of NFC debt securities in the post-crisis recovery.[48] More generally, the ratio between credit granted by non-banks to NFCs to credit provided by both banks and NBFIs has almost doubled from around 15% to close to 30% since the global financial crisis. The relative importance of NBFI holdings of listed shares compared to those of banks and NBFIs, however, has remained stable at the high level of around 80% (see Box 2).

The assets of other financial intermediaries (OFIs) have decreased substantially, predominantly on account of reductions in their unlisted share holdings. OFIs’ aggregate assets decreased by 2.5% (Statistical Annex Chart 37), reflecting international companies’ restructuring of their off-shore activities due to changes in international tax regulations and exchange rate fluctuations.

Chart 4

Investor base of debt securities issued by EA issuers

(percentage of amounts outstanding)

Sources: Euro area accounts reports, SHS and ECB calculations.

Note: Excludes financial vehicle corporations and remaining other financial institutions (OFIs).

Despite multiple ongoing international and European initiatives, harmonised central bank statistics still do not provide sufficient coverage of the way fintechs are transforming business. For example, the statistics lack insights into fintechs’ implications for relationships with different economic sectors in general and the euro area financial system in particular. Developing sound statistics covering these critical players is essential to monitoring advances in the financial system. Valuable initiatives have been launched at the international and European levels to increase the availability of information and improve the conceptual framework for fintech. The plan for a new Data Gap Initiative under the auspices of the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors envisages the development of prospective frameworks and data collections on fintech and financial inclusion.[49] The ongoing revisions to the International Standard Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC)[50] and the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE)[51]– both relevant for the preparation of national accounts and other economic and business statistics – are considering how fintech developments should be treated, and whether it is necessary to identify fintech activities separately in their hierarchical structures.[52] Finally, the concepts and accounting standards for compiling national accounts (the System of National Accounts, SNA 2008)[53] and external sector statistics (the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Seventh Edition, BPM7)[54] are currently under revision; part of the review process is considering the treatment of fintech and crypto assets.

Box 2

Measuring market-based and non-bank financing of non-financial corporations in the euro area

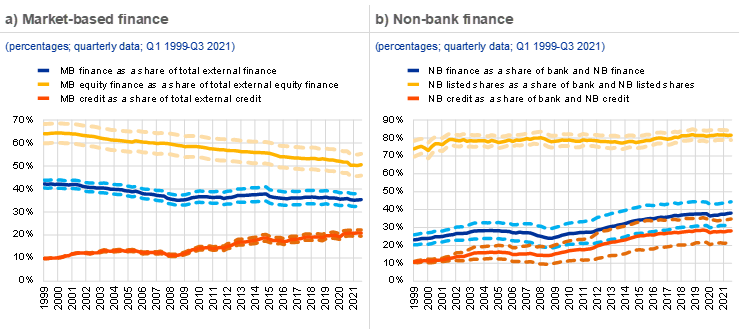

The importance of market-based credit and non-bank finance in the euro area has increased substantially in recent years. Total assets of the euro area non-bank financial sector have almost doubled to around €50 trillion over the last decade and now represent almost 55% of total euro area financial sector assets.[55] This trend is reflected particularly in the credit space by the greater use of marketable credit instruments such as debt securities issued by non-financial corporations (NFCs), while dynamics in the equity space differ. The outstanding amount of debt securities issued by euro area NFCs has roughly doubled over the past decade, growing from around €860 billion in January 2012 to around €1.6 trillion in December 2021.[56]

This box sheds light on these developments by designing and estimating two indicators of NFC financing: a market-based (MB) measure and a non-bank (NB) measure. The MB measure takes the instrument perspective: it computes the ratio of how much NFCs finance themselves by issuing marketable instruments (i.e. debt securities, securitised loans and listed shares) compared with non-marketable instruments (i.e. external loans and unlisted equity).[57] By contrast, the NB measure takes an entity perspective: how much financing do NFCs receive from non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) compared with their total financing from both NBFIs and banks, irrespective of the instrument used?[58] In addition, this box estimates these measures separately for credit and equity components. The two concepts of MB and NB finance are closely related, as NBFIs tend to hold a large share of marketable instruments. But they differ in scope, as the NB measure also includes the small but increasing amount of loans provided to NFCs by NBFIs. In addition, the NB measure considers only financing provided by banks and NBFIs, while the MB measure also covers financing provided by non-financial sectors such as NFCs, households and governments.

Since 2009, the relative importance of the NBFI sector in financing the real economy has increased significantly, whereas reliance on marketable instruments has not increased (Chart A). MB finance has in fact remained fairly constant at around 35% since 2009. However, this masks a doubling in MB credit alongside a significant decrease in MB equity, i.e. the share of listed equity over total external equity. By contrast, NB finance has increased significantly from 25% to close to 40%, driven in particular by a strong rise in NB credit and to a lesser extent by a slight increase in non-banks’ holdings of listed shares relative to banks’ holdings.[59]

Owing to data gaps, estimating the two measures requires several assumptions to be made. First, since there is no sectoral breakdown for financing received from non-euro area residents, the sectoral distribution of such financing is taken to be the same as in the euro area. Second, since the euro area sectoral breakdown for securities is only available since the fourth quarter of 2013, it has to be back-casted to previous quarters.[60] Third, information needed to exclude intra-group NFC financing is only partially available.[61] Fourth, the extent to which loans and equity granted and held by the other financial institutions sector (OFIs or “the OFI residual”) should be counted as external financing is unclear.[62] To tackle this, non-retained securitised loans are first separated out from loans granted by OFIs, with upper and lower bounds then calculated by either including or excluding all remaining loans and unlisted equity held by OFIs in the measures.[63] Finally, since the available equity data can be strongly driven by valuation effects, new time series are constructed: the outstanding amount in 1999 is taken as the starting point, and flows in the subsequent quarters are cumulated.[64]

Chart A

Market-based and non-bank financing of euro area NFCs, including their decomposition into credit and equity components

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts, balance sheet item statistics and financial vehicle corporation statistics) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Dotted lines represent the upper and lower bounds depending on whether the OFI residual is included as explained in the paragraph below. MB finance is defined as debt securities, non-retained securitised loans and listed shares over external loans and unlisted equity. MB equity is external listed shares over external unlisted equity. MB credit is debt securities and non-retained securitised loans over all external credit. NB finance is listed shares, (securitised) loans and debt securities held by NBFIs against those held by the total financial sector excluding central banks. NB equity is listed shares held by NBFIs against those held by the total financial sector. NB credit is credit held and granted by NBFIs against that provided by the total financial sector excluding central banks.