The future of central bank money

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, 14 May 2018

Slides from the presentationCentral bank balance sheets have received much attention in recent years, mostly reflecting their considerable expansion on the back of large-scale asset purchases and long-term lending operations. [1]

In my remarks this evening I would like to share some more general thoughts on the role of the central bank’s balance sheet in the economy. My focus will be on central bank liabilities – that is, money created by central banks to be used as a means of payment and store of value.

The development of private digital tokens based on the blockchain technology, which is the theme of one of the two Geneva reports that we will discuss tomorrow, has generated a debate over whether central banks should issue a new liability – their own digital currency – to the general public. While the Geneva report focuses on blockchain’s impact on finance, I will consider the potential broader impact on the economy of central banks issuing new forms of money. Since the general public already holds central bank liabilities in the form of banknotes and coins, this is clearly a question of how.

But I will also consider who. In an environment of excess liquidity and new regulatory requirements for financial market participants, broadening access to the liability side of central banks’ balance sheets to parties other than banks may help better align financial conditions with the central bank’s intended stance.

Central bank digital currencies

Who has access to the central bank balance sheet, and how, is a debate that has been going on for hundreds of years. In the early years of central banking, this discussion was mostly about the optimal provision of money as a means of payment. The banks of Amsterdam and Hamburg, for example, which are now considered as having performed key central bank functions as early as the beginning of the 17th century, were created to provide giro deposits as an efficient and stable method for merchants to pay each other, greatly facilitating trade.[2]

An anecdote from Sweden, where another early central bank was founded in the middle of the 17th century, demonstrates these benefits quite nicely. Coinage at that time was minted in copper but set to be the same value as silver. This meant so-called coins were the size of your dinner plates tonight. The largest one weighed just shy of 20 kilograms.

Clearly this was inconvenient for trade. Indeed, one tale tells of two thieves who tried to make off with 170 copper daler but couldn’t lift the coins above knee height.[3] The Bank of Stockholm addressed this problem by issuing the first modern banknotes.

More generally, central bank liabilities provided a convenient means of payment to allow clearing and establish trust in the financial system. But debate raged in the 18th and 19th centuries over the relative merits of different central bank liabilities. The universal nature of banknotes, and the possibility to use them in a decentralised way, eventually made them the more important central bank liability.[4]

But over time, technological advances, financial intermediation based on a stable bank-borrower relationship and the obvious inconveniences of currency – it can get lost, be destroyed or stolen – all led to banknotes gradually being superseded by bank deposits. Yet, repeated banking crises highlighted that commercial bank deposits were themselves vulnerable to runs, since banks’ assets are typically illiquid while their liabilities can be withdrawn at will.

This insecurity led central banks to gradually take on their role of lenders of last resort to avoid economically and socially disruptive banking crises, well before Henry Thornton (1802) and Walter Bagehot (1873) articulated their views on the subject.[5] But others, most notably James Tobin (1987), wanted to go further, allowing not only banks to deposit funds at the central bank, but also individuals.[6] Safety was his primary concern.

In many ways, this debate over the relative merits of banknotes and accounts, and over central banks and banks as main issuers of money, has once more returned.

With the recent fad about crypto assets, pioneered by bitcoin, the idea has been floated for central banks to issue their own digital currencies – let’s call them “universal reserves” – that would allow all individuals to hold central bank liabilities in the form of both banknotes and coins as well as electronic central bank reserves.[7]

What distinguishes the discussion today from previous discussions, however, are three new facts:

- The first is that we are seeing a dramatic decline in the demand for cash in some countries, in particular Sweden and Norway.

- The second is that central banks today could make use of new technologies that would enable the introduction of what is widely referred to as a “token-based” currency – one based on a distributed ledger technology (DLT) or comparable cryptographic technology.

- And the third “new” fact, at least from a long-term perspective, relates to the role of central banks in setting monetary policy, and more recently to the emergence of negative rates as a policy instrument and the consequences for the transmission of monetary policy.

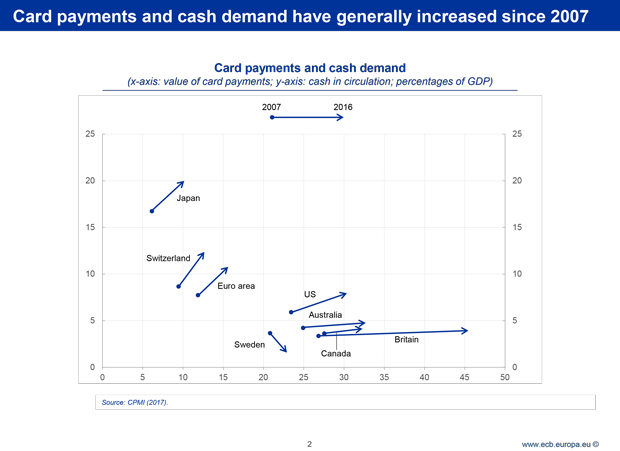

I would argue that, in most countries, the first fact – the disappearance of cash – is not a cause for imminent action. You can see this on my first slide. Demand for banknotes is still growing around the world, and in the euro area cash remains a popular means of payment.

The second fact is the subject of the first report that will be presented tomorrow: distributed ledger technologies. Universal reserves could be implemented in principle either as central bank deposits – this was Tobin’s original idea of “deposited currency accounts” – or as DLT-based digital tokens.

Digital tokens – call them “FedCoin”, “ECBCoin” or why not “BIScoin” – are different in two main ways. First, they would save the central bank the operational risks and costs related to administering individual central bank accounts for millions of households and companies. Second, they may share one of the key features of cash, namely that the identity of the holders would – at least in principle – not be known to the central bank.[8]

However, the technology is still immature, costly to maintain and possibly prone to vulnerabilities. Existing retail payment systems, on the other hand, are convenient, efficient and reliable and have earned public trust. Today they may be slower and costlier than schemes based on crypto assets, but with the introduction of 24/7 instant payments in many jurisdictions – and assuming that similar efforts can be made to improve the cost, timeliness and transparency of cross-border payments[9] – they appear to still be superior to what we have seen from crypto assets thus far. The same holds true, for the moment, for wholesale payment systems, even if distributed ledgers show more promising applications in that area.[10]

That being said, developing economies’ successful experience with mobile payment systems suggests that cash may be sidelined sooner rather than later, even in economies where it today reigns supreme.[11] Indeed, our own efforts to upgrade retail payment systems may even be accelerating this evolution.[12]

In a not so distant future, universal reserves could enable people to hold a central bank liability comparable to cash, without the risks associated with commercial money. The social consequences of such an evolution deserve a more thorough discussion. But one anecdote emphasises the risks of leaving the public sector exposed to private payment systems.

In 2010, two bitcoin enthusiasts agreed to exchange two large pizzas for the price of 10,000 bitcoins. In a forum one of them wrote: ”I'll pay 10,000 bitcoins for a couple of pizzas… like maybe two large ones so I have some left over for the next day.”[13] At that time, 10,000 bitcoins were worth about €32. Today, 10,000 bitcoins are worth more than €70 million. Last year, this would have been enough to buy Van Gogh’s 1889 painting “Laboureur dans un champ”. So, as it stands today, bitcoin is bad money and a poor payment system.

Universal reserves and the transmission of monetary policy

Much of the historical discussion on central bank liabilities developed at a time when monetary policy was quite different from how we know it today. Central banks now play a more active role in macroeconomic management, meaning that they would need to carefully consider the costs and benefits that issuing a digital currency would have for the conduct of monetary policy – the third fact I mentioned before.

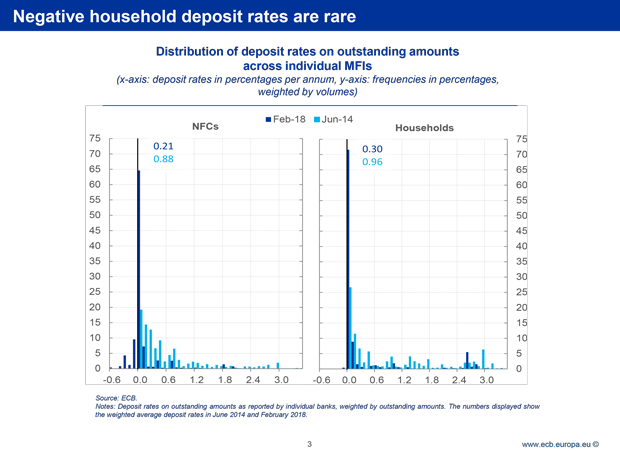

You can see the potential motivation for this on my next slide.

Although the Eurosystem has been charging an annual interest rate of -0.4% on banks’ excess reserves for more than two years now, almost no euro area banks have passed these negative rates on to their household clients. In some jurisdictions this is due to legal impediments, but in most cases it simply reflects banks’ long-run perspective – that is their efforts to maintain a sustainable source of profit and, hence, a stable deposit base.

This rigidity does not only blur the transmission of our policy rates. Empirical evidence suggests that it also weakens the bank lending channel. A decline in the policy rate typically lowers the cost of banks’ liabilities first, thus increasing their net worth and relaxing their financial constraints, which causes them to increase lending.[14] But if negative rates are not passed through, this channel will fail to develop to its full potential.

An interest-bearing central bank digital currency may help overcome these constraints. This does not actually require cash to be abolished, but rather that it no longer acts as an effective competitor for large transactions.[15]

Under these conditions the central bank could gain greater control over the transmission of interest rates to households and businesses. In a deep recession, it could reduce interest rates by more than is currently possible and stabilise economic activity more quickly, reducing the need for other non-conventional measures. And in an upswing, the ability to pay positive interest rates on digital currency would put increased upward pressure on deposit rates provided by banks.

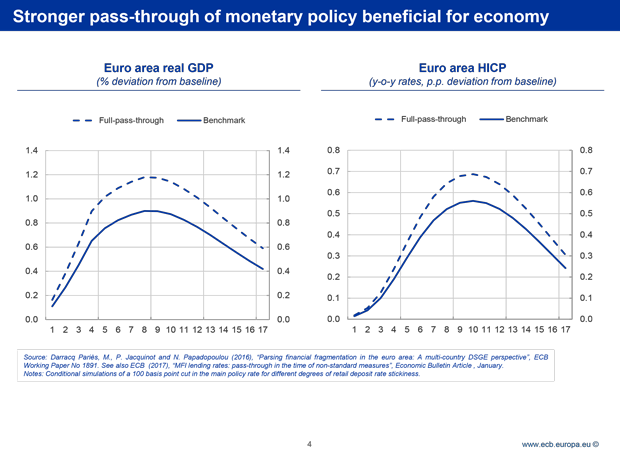

The potential effects on output and inflation could be sizeable.[16] You can see this on my next slide, where ECB staff have used a medium-scale structural macro-finance model to simulate the macroeconomic effects of a stronger pass-through of a conventional 100 basis point cut in our main refinancing rate.

The benchmark – the solid blue line – is how we would currently expect output and inflation to react, given the empirical evidence of banks’ sluggish pricing behaviour. The dashed line shows the effects we would observe under a full pass-through scenario. You can see that, at the peak, both output and inflation would increase by around 30% more than under the baseline scenario.

In the case of negative interest rates, however, the benefits might be less clear-cut. On the one hand, banks’ interest margins may be better protected by a higher pass-through to households, pushing down the economic lower bound (or “reversal rate”) at which negative rates are thought to become contractionary.[17] On the other hand, faced with very negative rates, households might start saving more rather than less. Given the downward rigidity in retail rates, and the fact that households often suffer from money illusion, household consumption planning with nominal negative interest rates is unchartered territory.

Digital bank runs and the future of financial intermediation

This brings me to the potential dark side of universal reserves.

Interest-bearing universal reserves would directly compete with bank deposits. In a systemic crisis, despite the protection provided by government deposit guarantee schemes, households and businesses could seek to hold their wealth in the riskless central bank liability rather than the riskier private sector one.[18] While this shift could also happen now between deposits and cash, a digital currency would make it cheaper and faster, making “digital bank runs” more frequent and more severe.

In the steady state, the risk is that households and firms find digital currency more convenient than bank deposits, depriving banks of a stable source of funding and undermining their social role at a time when some of their other functions, such as the provision of payment services, are already severely challenged by new entrants.[19]

In the euro area, for example, non-monetary financial institutions have considerably expanded their share of financial intermediation in recent years. In terms of total assets, their share increased from 43% in 2008 to 55% in early 2017.[20] Fintechs are also challenging the role of banks in providing credit.[21] In other words, maturity transformation still plays an important role, but it is no longer the sole preserve of banks.

This means that universal central bank reserves may accelerate the euro area’s journey towards a less bank-based economy.

I see two reasons why this could be problematic. First, in spite of recent regulatory initiatives, the externalities created by maturity mismatch in market-based finance aren’t nearly as well addressed as those created by banks.[22] Second, financial structures should be the outcome of market forces. They should be driven by consumer preferences and technological change, and constrained as needed by regulation, including antitrust law. In other words, central banks should, in principle, play no active role here.

So, before taking decisions that could potentially nudge the financial system away from traditional, deposit-based financial intermediation, we should carefully ponder the consequences from issuing universal reserves for both financial stability and the financial system’s ability to match savings and investment in an efficient manner.[23]

Safe asset scarcity and the dispersion of short-term interest rates

Either way, it’s likely that universal central bank reserves would fundamentally transform many aspects of today’s financial system. But there could be a case for a more incremental reform, consisting of widening access to central bank liabilities to a broader but limited range of financial market participants.

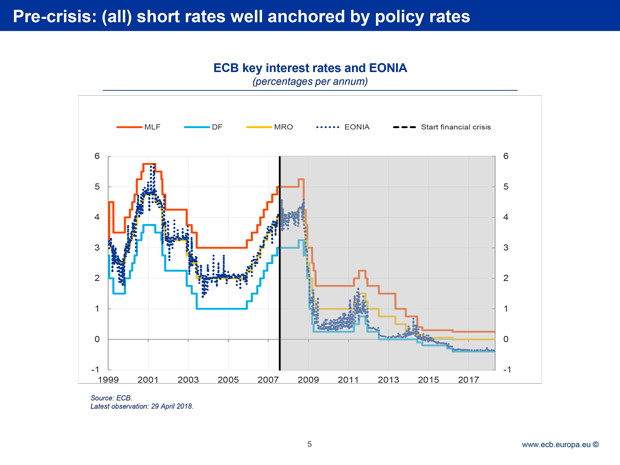

As you know, when central bank reserves are in short supply – that is, they are just sufficient to satisfy the demand for banknotes and other autonomous factors – access to central bank facilities by credit institutions has in the past ensured that very short-term interest rates were closely aligned with the interest rate at which the central bank provides reserves.[24]

You can see this for the euro area on my next slide. From the launch of the euro up to the global financial crisis, unsecured short-term interbank rates lay within the corridor bounded by the ECB’s marginal lending facility and deposit facility rates and were concentrated around our main policy refinancing rate.

This relationship did not fundamentally change in 2007 with the emergence of the financial crisis. But when we granted unlimited liquidity to our counterparties against sound collateral, and when we later started purchasing assets, an environment of excess reserves caused unsecured money market rates to converge towards the deposit facility rate.

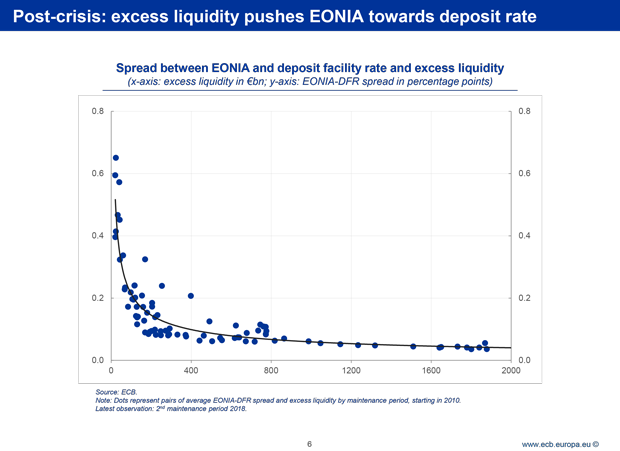

You can see this on my next slide. Whenever excess liquidity is large, the spread between the EONIA and the deposit facility rate narrows, as the latter is the rate that determines the marginal cost of interbank lending when there is excess supply of central bank reserves. This was fully in line with our policy intentions. Our policy framework was able to provide a hard floor, at our desired level, for the EONIA.

At the same time, the transmission of our policy intentions started to become less uniform as excess liquidity mounted.

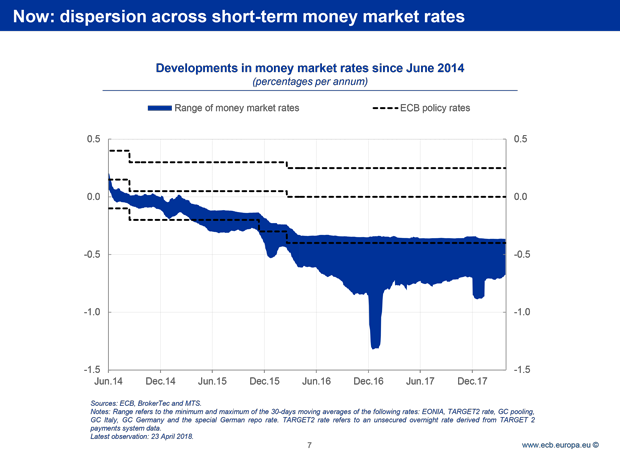

You can see this on my next slide. In the past, different short-term rates, such as unsecured money market rates or repo rates backed by either general or security-specific collateral, on average moved in tandem and the spread between them was typically very small and rather stable over time.

But as excess liquidity increased, these rates started to diverge. As you can see from the chart, most money market rates have remained below the ECB’s deposit facility rate, sometimes by a substantial margin.

Some of these divergences are transitory and have no broader implications for monetary policy. Regulatory “window-dressing”, for example, causes repo rates to decline on balance sheet reporting dates, but they typically bounce back quickly. You can see this clearly at year-ends, in particular in December 2016.

Other divergences, however, have proved more permanent and have sometimes been rising with the level of excess liquidity. The reason for this is that many of the ultimate holders of the securities we purchase under our asset purchase programme are either non-banks – typically, asset managers, pension funds, insurance companies or corporate treasurers – or banks located outside the euro area. And although central bank asset purchases in effect replace one safe asset with another – central bank reserves with government bonds – differences in who can hold these assets may result in persistent price effects.

In other words, while the deposit facility rate provides an effective floor for direct monetary policy counterparties (i.e. banks) and those with access to the facility, other financial market participants must look elsewhere for safe and liquid investments. Although banks are willing to accept cash from the latter and deposit it at the central bank, this service is not for free, as banks’ balance sheet capacity has become costly.[25]

This means that in an environment where the supply of safe assets shrinks and where demand for them increases, due to changes in regulation for example, safe and liquid short-term assets other than central bank reserves become scarce.[26]

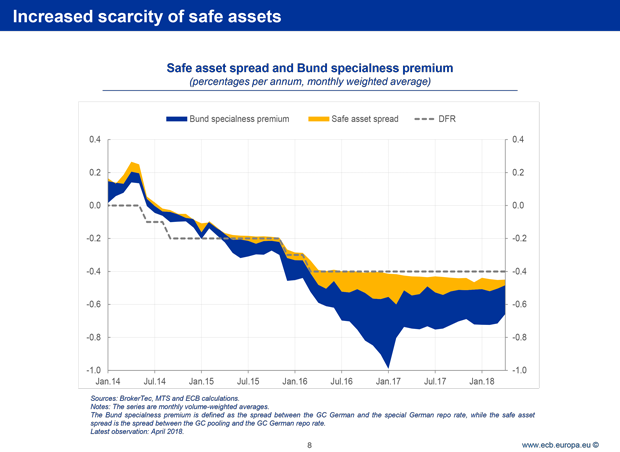

You can see this on my next slide. Next to central bank reserves, Bunds are typically considered the safest and most liquid financial instrument in the euro area. As a result, our purchases, together with the growing demand from non-counterparties, have caused the Bund’s “specialness” premium to widen noticeably over time.

The Governing Council’s decision in December 2016 to also accept cash as collateral in our securities lending facility successfully stopped the spread from widening further. But there remains a persistent and sizeable spread between unsecured interbank rates and repo rates backed by scarce safe collateral.

Such protracted dispersion of short-term rates may matter for three broad reasons.

- First, there may be a social cost.[27] Market allocation of funds requires the real costs of intermediation to have genuine price signals so lenders and borrowers can be matched for the lowest cost. When institutional arrangements create wedges between different short-term rates, funds may be inefficiently matched, potentially creating a deadweight loss.

- Second, the current arrangement under which credit institutions have privileged access to central bank facilities is the outcome of their historical monopoly role in collecting deposits and lending to the economy. To the extent that a growing and increasingly diverse range of market participants starts to offer similar services, structural disparities in their ability to place safe and liquid investments may become a source of concern.

- And third, the dispersion of short-term rates may affect the transmission of our monetary policy stance. In effect, it could make overall financial conditions looser or tighter than we intend.

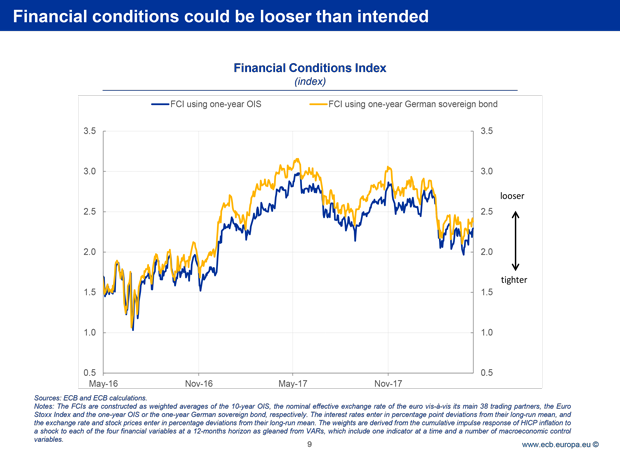

To demonstrate this, on my next slide I show so-called financial conditions indices, which are simple summary indicators of the monetary policy stance. They are weighted averages of developments in short and long-term interest rates, exchange rates and stock markets, with the weights determined by the variable’s importance for policy transmission.

You can see that such indicators would, at times, have pointed towards a measurably looser stance when using the one-year German sovereign bond as the short-term rate as opposed to the one-year overnight indexed swap rate that is typically used to calculate these measures.

Such differences, if persistent, may entail real economic effects.

The reason for this is that banks typically price their loans off market interest rates, and in some instances they use the prevailing sovereign yield curve. This could lead to banks pricing loans differently when short-term rates diverge, thereby affecting the ultimate borrowing conditions of households and firms.

In other words, it may well matter for banks whether the actual opportunity cost for issuing a short-term loan is -70 basis points, the year-to-date average of the yield of a three-month German Treasury bill, or -33 basis points, the current rate of the three-month EURIBOR. In fact, differences in sovereign rates across Member States were the key reason for the significant dispersion in bank lending rates that we observed in the midst of the euro area sovereign debt crisis.

None of this can be observed today, of course. Thanks to our unconventional policy measures, bank lending rates in the largest euro area countries have converged to a degree not seen before.

But the divergence between our key policy rates and market rates could become more important in the future once policy rates begin to normalise. Let me be clear: this is not a short-term concern. The Governing Council expects our key policy rates to remain at their present levels for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases.

But looking beyond, with our reinvestment policy ensuring continued excess reserves, there is a risk that, under the current framework, some short-term market rates would not respond fully to changes in our key interest rates or, even if they would, that a continued dispersion of short-term rates would adversely impact the transmission of our monetary policy stance.[28]

The case for widening access to central bank liabilities

One possible way to overcome this situation, if and when needed, would be to consider expanding access to the liability side of central bank balance sheets to other actors in financial markets.

There are various ways to do this. I will not discuss these options in detail today. But the important thing to note is that this could help tie the range of short-term rates more closely to our policy stance, mainly by relieving downward pressure on the “scarcity premium” of some safe assets.[29] For these reasons, some central banks have already successfully widened access, such as the Federal Reserve via its overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility.

In the euro area, some non-bank market players already have access to the liability side of our balance sheet via account facilities. Central counterparties (CCPs) from the European Economic Area, for example, can open a settlement account subject to the harmonised terms and conditions of the TARGET2 Guideline.[30]

CCPs often need to manage significant cash amounts that they receive as collateral from their clearing members. If they invest these cash amounts in the market, they need to largely collateralise the investments with high-quality liquid assets in accordance with prudential requirements. Allowing CCPs to leave their funds at the central bank may, therefore, have somewhat eased downward pressures on some market rates, including repo rates backed by the safest collateral.

Of course, any expansion beyond the current regime would have to respect the ECB’s Treaty obligations. Our deposit and marginal lending facilities are instruments of monetary policy and our rules for opening central bank accounts also take monetary policy needs into account. Extending them to other counterparties would have to be consistent with that objective.[31]

Before reaching this conclusion we need to carefully study whether allowing non-banks to leave deposits at the ECB overnight would, first, have a tangible effect on those short-term rates that are currently trading at a noticeable spread below our deposit facility rate and, second, whether and to which extent these rates are ultimately significant for the transmission of our monetary policy stance.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Technological advances, changes in the structure of the financial system and recent monetary policy developments all mean that, in the future, central banks will need to consider whether the current arrangements for accessing their balance sheets are optimal.

It doesn’t only matter how central bank money is created, but also to whom it is issued.

From today’s perspective, there are no clear benefits from allowing the general public to hold digital central bank reserves, in particular in economies where demand for cash remains robust, such as in the euro area. This assessment includes considerations related to the potential impact of central bank digital currencies on financial structures in general, and the stability of bank deposits in particular.

In the medium term, a more incremental reform could consist of giving a broader range of financial market participants access to the liability side of the central bank’s balance sheet, provided that this can help strengthen the transmission of monetary policy in an environment of excess liquidity.

Thank you.

[1] I would like to thank Fabian Eser and Christoph Ohlerich for their contributions to this speech and Ulrich Bindseil and Benjamin Sahel for their comments. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

[2] See, for example, Roberds, W. and F. Velde (2014), “Early Public Banks”, Working Paper No 2014-03, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago; Bindseil, U. (2018), “Pre-1800 central bank operations and the origins of central banking”, mimeo; and Ugolini, S. (2011), “What do we really know about the long-term evolution of central banking? Evidence from the past, insights from the present”, Norges Bank’s bicentenary project, Working Paper 2011/15.

[3] See Wetterberg, G. (2009), Money and Power, From Stockholm’s Banco 1656 to Sveriges Riksbank Today.

[4] In the 18th century, the size of the balance sheet of banknote-issuing central banks, such as the Bank of England or the Caisse d’ Escompte, easily surpassed that of their older cousins in Amsterdam and Hamburg, which continued to rely exclusively on deposits

[5] See, for example, Bindseil, op.cit.; and Schnabel, I. and H.S. Shin (2004), “Liquidity and contagion: the crisis of 1763”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 2, pp. 929-968.

[6] See Tobin, J. (1987), “The case for preserving regulatory distinctions”, Proceedings of the Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 167-83.

[7] For an overview, see Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Markets Committee (2018), “Central bank digital currencies”, Bank for International Settlements, March; and Cœuré, B. and J. Loh (2018), “Bitcoin not the answer to a cashless society”, op-ed published in the Financial Times, 13 March. The BIS report also discusses a second option of introducing a central bank digital currency, namely in the form of restricted-access digital settlement tokens for wholesale payment and settlement transactions.

[8] In reality, current private crypto assets only allow for pseudo-anonymity, as all transactions are publicly recorded. But users do not necessarily have to reveal their true identities.

[9] See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (2018), “Cross-border retail payments”, Bank for International Settlements, 16 February.

[10] See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Markets Committee, op. cit. Joint research by the ECB and the Bank of Japan has found that distributed ledger technologies are not (yet) mature enough for large wholesale payment systems. See Bank of Japan and ECB (2017), “Payment systems: liquidity saving mechanisms in a distributed ledger environment”, Report on the STELLA project.

[11] See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and World Bank Group (2016), “Payment Aspects of Financial Inclusion”, Bank for International Settlements, April.

[12] See, for example, “We don’t take cash’: is this the future of money?”, Financial Times, 10 May 2018.

[13] Source: Bitcoin Forum, 18 May 2010.

[14] See Heider, F., F. Saidi and G. Schepens (2018), “Life Below Zero: Bank Lending Under Negative Policy Rates”, mimeo, available on SSRN.

[15] For example, scalable deposit and withdrawal fees, as proposed by some academics, would allow cash to still be used for small, necessary transactions while penalising large holdings more severely. See Goodfriend, M. (2016), “The Case for Unencumbering Interest Rate Policy at the Zero Bound”, prepared for the 2016 Economic Policy Symposium Proceedings, Jackson Hole: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 26 August; Agarwal, R. and M. Kimball (2015), “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound”, IMF Working Paper No 15/224; and Rogoff, K. (2014), “Costs and Benefits to Phasing Out Paper Currency”, NBER Working Paper No 20126.

[16] This analysis does not consider any potential disintermediation of the banking sector as a result of the introduction of a central bank digital currency.

[17] See Cœuré, B. (2016), “Assessing the implications of negative interest rates”, speech at the Yale Financial Crisis Forum, Yale School of Management, New Haven, 28 July; and Brunnermeier, M. and Y. Koby (2018), “The Reversal Interest Rate”, Princeton University, mimeo.

[18] In this sense, considerations related to the introduction of universal reserves are also linked to the parallel discussion on the future size of central bank balance sheets, where some academics argue that central banks should keep balance sheets close to current levels in an effort to promote financial stability by providing a safe asset (see, for example, Greenwood, R., S. G. Hanson and J. C. Stein (2016), “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet as a Financial-Stability Tool”, paper prepared for the 2016 Economic Policy Symposium Proceedings, Jackson Hole: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City).

[19] For an illustration of this risk in relation to the Swiss “Vollgeld” initiative, see Jordan, T. (2018), “Why sovereign money would hurt Switzerland”, speech at the Swiss Institute of Banking and Finance at the University of St. Gallen, Zürich, 3 May.

[20] See, for example, ECB (2017), “Report on financial structures”, October.

[21] See Cœuré, B. (2017), “The known unknowns of financial regulation”, panel contribution at the conference on Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy IV, Washington D.C., 12 October.

[22] See Financial Stability Board (2017), “Assessment of shadow banking activities: risks and the adequacy of post-crisis policy tools to address financial stability concerns”, July.

[23] This includes a more thorough discussion on the design features of universal reserves that could potentially help mitigate a destabilising shift away from bank deposits.

[24] Interbank rates can also be steered towards the main refinancing rate in an environment of excess reserves. But this requires additional liquidity-absorbing operations.

[25] Moreover, investors are limited in what they can invest with banks due to their own risk control frameworks.

[26] See also Cœuré, B. (2017), “Bond scarcity and the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the Club de Gestion Financière d’Associés en Finance, Paris, 3 April; and Cœuré, B. (2017), “Asset purchases, financial regulation and repo market activity”, speech at the ERCC General Meeting on “The repo market: market conditions and operational challenges”, Brussels, 14 November.

[27] See also Duffie, D. and A. Krishnamurthy (2016), “Passthrough Efficiency in the Fed’s New Monetary Policy Setting”, paper prepared for the 2016 Economic Policy Symposium Proceedings, Jackson Hole: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

[28] It may be argued that overall financial conditions always and everywhere reflect a constellation of interest rates embedding different term and credit premia. But the central bank’s control of short-term interest rates is essential to signal its monetary policy stance and helps market participants form their interest rate expectations.

[29] See also D'Amico, S., R. Fan and Y. Kitsul (2013), “The Scarcity Value of Treasury Collateral: Repo Market Effects of Security-Specific Supply and Demand Factors”, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper No 2013-22; and Corradin, S. and A. Maddaloni (2017), “The importance of being special: repo markets during the crisis”, ECB Working Paper No 2065.

[30] Depending on the bilateral arrangements between the CCP and the national central bank holding the account, the CCP may be permitted to hold positive overnight balances on the settlement account. Such overnight balances have an interest rate of either 0% or the deposit facility rate, whichever is lower.

[31] Under Article 127(2) first indent of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts