Unconventional monetary policy and fixed income markets

Remarks by Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB,

at the Fixed Income Market Colloquium, Rome, 4 July 2017

Well-functioning fixed income markets are at the heart of modern market economies. There are several reasons for this:

- they provide information to market participants and policymakers concerning the state of the economy and how it is expected to develop;

- they signal monetary policy expectations and investors’ expectations regarding future inflation;

- they offer benchmarks for pricing other assets.

In times of unconventional monetary policy, fixed income markets acquire an extra dimension: they become key channels through which the central bank seeks to influence long-term interest rates directly – through expanded guidance about its intentions for future policy, or through purchases of long-dated securities – in an attempt to ease financial conditions beyond what would be feasible with conventional tools, and thereby support economic activity and the central bank’s inflation objective.

Is there a tension between these two functions of fixed income markets in times of unconventional monetary policy: as aggregators of information, and as a channel of additional stimulus?

In the ECB’s experience, this tension has been less than anticipated. First, as we started to offer forward guidance and, later, as we signalled the beginning of active interventions in long-dated securities, fixed income markets were still distorted, to a certain extent, by the illiquidity and excess risk aversion that had influenced price formation in those markets at the height of the sovereign debt crisis. Under those conditions, fragmentation of relative-value relationships across yield curves had made it harder to identify forward interest rates and break-even rates of inflation. In other words, the role of those markets as collectors and aggregators of information was already compromised. Our interventions contributed to restoring market functioning. In doing so, we eliminated the substantial noise that was blurring the information signals emanating from fixed income markets.

Second, fixed income markets don’t seem to have lost their capacity to discern and express their views on the creditworthiness of financial assets. The last few months have demonstrated that, despite the ECB’s continuing presence in the market as a large investor, market prices have tended to reflect investors’ evolving views about the prospective standing of sovereign issuers’ credit.

Building on these observations, in my remarks today I would like to outline the rationale behind our interventions in recent years and how effective they have been.

* * *

For some years, major central banks have been intervening in fixed income markets with the intention of providing substantial amounts of stimulus to their respective economies and delivering on their mandates. Their interventions ultimately rest on the same premise: when the overnight money market rate typically used by central banks as a policy instrument reaches a level that cannot be further reduced to any meaningful extent, the natural progression is to extend the maturity range of interest rates that the central bank seeks to influence.

This can be done in two ways, which strongly complement each other. First, by influencing expectations of short-term interest rates via signalling channels, and second, by central bank purchases of long-dated securities which crowd out private demand for such instruments, making them more expensive and thereby encouraging portfolio rebalancing. Both instruments have the same purpose – exerting downward pressure on long-term yields. This is why they complement each other and rely on one another to be effective. Asset purchases almost certainly enhance the credibility of a central bank’s signals that it will follow a certain course of action for setting policy rates in the future, as these purchases are a concrete demonstration of a desire to provide additional stimulus. So, the anchoring of rate expectations is reinforced by asset purchases. And, conversely, the net stimulus provided by asset purchases through compression of the term premia depends, in part, on expectations of how policymakers will adjust short-term interest rates in the future in response to the stronger real activity and inflation sparked by lower term premia. If short-term interest rate expectations are not well anchored throughout the life of the asset purchase programme and are allowed to creep upwards, then the entire exercise to ease financial conditions becomes self-defeating. This is why anchoring interest rate expectations is a key condition for asset purchases to deliver accommodative monetary policy.

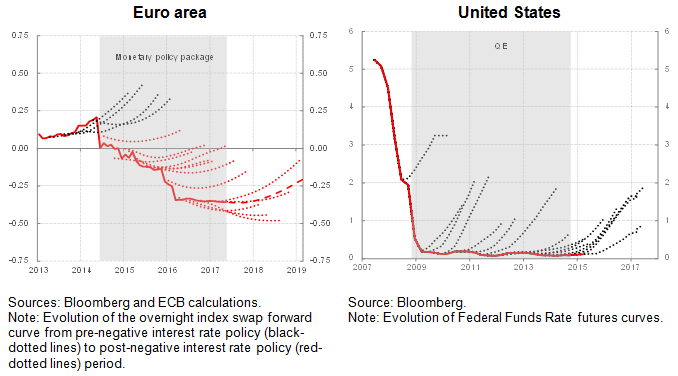

From this perspective, the ECB has been very effective in designing and implementing its programme. As demonstrated by the overnight index swap forward rate curve, once we launched our monetary policy package in mid-2014, the short-to-medium segment of the curve, which arguably reflects investors’ rate expectations most clearly, shifted down and became flatter (see Chart 1). This reaction is especially striking when compared to the US experience during the period in which the Federal Reserve carried out its large-scale asset purchases. One reason why interest rate expectations have been well-anchored in the euro area is that the introduction of the negative interest rate policy has been effective in making the signalling channel, which is implicit in our forward guidance, more compelling and credible.

Chart 1: Anchoring short-term interest rate expectations

Expectations of future short-term rates throughout periods of non-standard measures

(percentages per year)

Importantly, in order to anchor short and medium-term interest rates at levels that are close to the lower bound, this portion of the curve had to be insulated from flows of news that otherwise would have entailed an unwarranted change in the monetary policy stance. The conceptual basis for this is exactly the same as the one that, in ordinary times, justifies the tight control that central banks exert on the overnight rate. Ordinarily, the central bank “targets” the overnight interest rate, which implies that it seeks to protect that rate from shocks – say, originating in the interbank market for liquidity or elsewhere – that, if not offset, would nudge the monetary policy stance in directions that would not be appropriate, given the state of the economy. As I said before, in unconventional monetary policy times, as the overnight rate becomes increasingly constrained to the downside, the notion of the “operating target” is generalised to encompass a whole range of interest rates with longer maturities. Consequently, insulating those interest rates, to the extent possible, from the impact of external surprises that should not alter the stance becomes an important precondition for a successful reflation strategy.

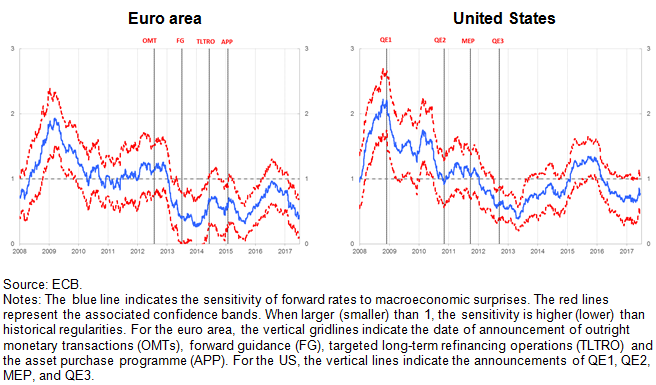

In this regard, over the past three years one could say that we have been effective in shielding short-to-medium term interest rates from shocks that could have weakened the stimulus that the euro area needed to consolidate the recovery (see Chart 2).

Chart 2 : Shielding short-to-medium term interest rates from news shocks

Sensitivity of euro area (1 year-in-2 year) forward rates to macroeconomic news

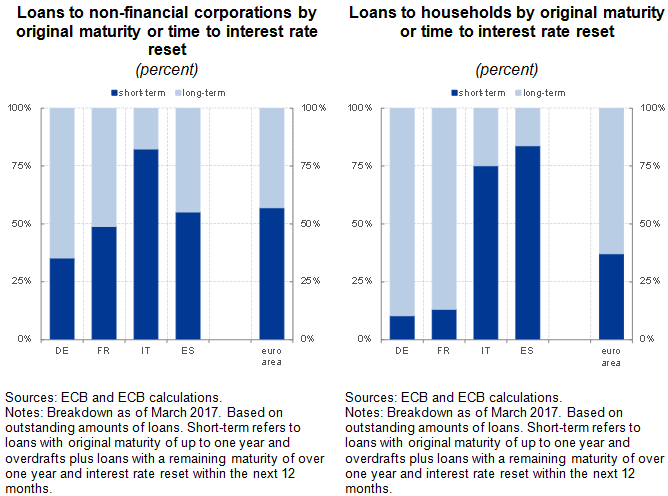

Anchoring the short and intermediate segments of the yield curve around levels consistent with a very accommodative monetary policy stance has been even more critical for us at the ECB than for other central banks engaging in similar policies. The reason for this reflects the unique structure of the euro area’s monetary policy transmission mechanism. Compared with the United States, for example, transmission in the euro area is much more reliant on banks. And short-to-medium term rates are very important benchmarks that euro area banks use for pricing loans, notably to non-financial corporations. One way to see the connection between euro area credit markets and different segments of the yield curve in the euro area is to look at the interest rate fixation periods for loans to non-financial corporations and households (see Chart 3). Interest rates on loans to non-financial corporations are, by and large, based on shorter-duration interest rates, even in countries in which the rate fixation period for bank credit is generally longer. As regards setting mortgage interest rates, the picture is more dispersed, with short and medium maturities being the relevant benchmark in some euro area countries, and long-term interest rates in others.

Chart 3: Maturity structure of euro area loans

From this perspective, the complementary nature of our instruments – with forward guidance anchoring the short-to-medium term segment of the curve, and the asset purchase programme acting on the long-term segment – has given our monetary policy strategy an extra edge over the last few years. It has made it more targeted and thus more impactful.

* * *

As the economic prospects brighten, higher expected returns on business investment will make borrowing conditions increasingly attractive. This, in and of itself, will reinforce accommodation and make sure that inflation sustainably converges towards our objective of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

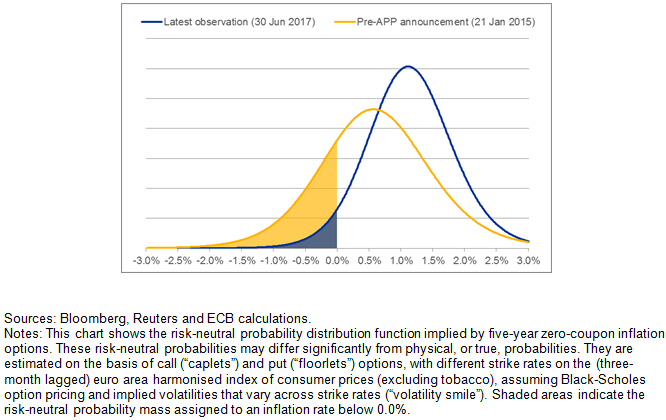

But our mission is not yet accomplished. We need patience and persistence. We need to be patient, because inflation convergence needs more time to show through convincingly in the data. The euro area’s economic environment is improving, and the fat negative tail to inflation expectations, which was so visible at the start of our asset purchase programme, has virtually disappeared (see Chart 4). This strengthens our confidence that headline inflation will gradually move towards the Governing Council’s objective. But measured inflation remains exceedingly volatile and metrics of underlying price pressures continue to be subdued. The entire distribution of inflation expectations still needs to shift a fair distance to the right.

Chart 4: Option-implied inflation expectations

Risk-neutral probability density function of euro area inflation over the next five years

And we need to be persistent, because the baseline scenario for future inflation remains crucially contingent on very easy financing conditions which, to a large extent, depend on the current accommodative monetary policy stance.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts