- SPEECH

The Euro Area's Exchange Rate Policy and the Experience with International Monetary Coordination during the Crisis

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECBat a conference entitled “Towards a European Foreign Economic Policy” organised by the European Commission

Brussels, 6 April 2009

Introduction

Ladies and gentlemen, it is a pleasure to be here today. The title of today’s conference “Towards a European foreign economic policy” could hardly be more topical. Indeed, the world is facing challenges not seen for decades – challenges that are truly global. The solutions will thus need to be global too.

Inevitably, the political power and economic weight of individual states and regions will matter when designing these global solutions. If Europe wants to punch in proportion to its economic weight, moving towards a common foreign economic policy is essential. I have expressed my preference for such a policy on various occasions.

In the area of exchange rate policy – the topic of my speech today – the euro area has already achieved unity. It speaks with one voice. Exchange rate policy is the exclusive competence of the Community. Hence, the individual Member States can no longer act autonomously in this field.

At the same time, in its resolution of 1997, the European Council stated that “exchange rates should be seen as the outcome of all other economic policies”. This represents a general feature of exchange rate policies, as the exchange rate cannot be determined by one single actor. It always depends on the decisions and actions of at least two parties. Indeed, any bilateral exchange rate depends on the actions and policies of both sides. Moreover, this rate can also be influenced by the actions and policies of third countries.

As a consequence, exchange rate policy is by nature international and needs to operate in a context of international cooperation. The euro area’s exchange rate policy cannot be seen in isolation from those of the US, Japan, China, and many others.

The international dimension of exchange rate policy and its implications for global economic stability came sharply into focus during the 1930s, when a series of competitive devaluations plunged the world into an economic depression. For this reason, the Bretton Woods conference assigned a central role to the IMF in the monitoring of exchange rate policies. Given the deepening integration of the world economy over the last decade, the IMF decided in 2007 to strengthen its surveillance of exchange rate developments, in particular to ensure that exchange rate policies do not jeopardise the stability of the world economy.

Today I intend to cover four items: the implications of the single currency for exchange rate policy, the institutional arrangements for the euro area’s exchange rate policy, exchange rate developments during the crisis and, finally, some other dimensions of international monetary cooperation.

A single currency – a single exchange rate policy

What did the creation of the euro mean for exchange rate policy? Prima facie, the answer is straightforward. Having a single currency automatically implies having a single exchange rate and thus also a single exchange rate policy. Yet the repercussions of EMU go beyond these ‘automatic’ consequences.

Prior to EMU, Europe consisted of open and, for the most part, small economies. Because of the very large size of the external sector compared with the national economy, the exchange rate played a very important role in the economic performance of these countries. The move to monetary union implied the creation of a new economic entity –‘euroland’ – which is much bigger and much more closed than its component states. This obviously reduces the importance of the exchange rate for ‘domestic’ economic developments.

In addition, monetary union – by definition – did away with nominal exchange rates between its participants. As a result, gone are the days when an economic or financial crisis could also trigger an exchange rate crisis.

By setting up a bigger and less open economic entity and by eliminating intra-area exchange rates, the euro acts as a shield against external turbulence.. The economic crisis has clearly demonstrated this. In rough financial waters, it pays off to be on a large, solid and stable ship rather than on a small vessel. Size matters in a global world. Allow me therefore to make a bold point: the euro has arguably been the best exchange rate policy decision which Europe has ever taken.

Institutional arrangements for exchange rate policy in the euro area

This brings me to my second topic: the institutional arrangements for the euro area’s exchange rate policy. In describing these arrangements, we should distinguish between three categories of countries: EU countries which do not take part in ERM II, EU countries which are part of ERM-II, and non-EU countries.

First, consider the EU countries which do not take part in ERM II. As EU Member States, these countries are subject to the Treaty. And the Treaty is crystal clear: each country must treat its exchange rate policy as a matter of common interest. [1] This obligation should not be taken lightly. In fact, it should be taken very seriously. The question arises whether the single market can function smoothly when the exchange rate is allowed – or even encouraged – to depreciate sharply. Using the exchange rate as an instrument to gain a competitive advantage over others may fuel resentment and stoke protectionist pressures. It falls upon the Commission and the Council to ensure respect for this Treaty provision.

Second, consider the EU countries which do take part in ERM II. ERM II is an exchange rate arrangement that links the currencies of some EU Member States outside the euro area with the single currency. The framework helps to ensure that euro area candidates orient their policies towards stability and sustainable convergence. By simulating some of the economic conditions which exist within a monetary union, ERM II also functions as a ‘training room’ which prepares and helps prospective euro area entrants on their road towards adopting the euro.

Finally, with respect to non-EU countries, the euro area has adopted a flexible exchange rate regime. The external value of the euro vis-à-vis the currencies of third countries is thus determined by the market. By adopting this line, the euro area has continued the policy towards third countries pursued by its component countries prior to EMU. The rationale behind this decision is twofold. First, the absence of an exchange rate commitment allows the ECB to focus squarely on its euro area objective, which is the preservation of price stability. Second, the creation of the euro implied the creation of a bigger and less open economic entity – the euro area – in which the exchange rate plays a much less influential role. Accordingly, it would have been nonsensical to subject the euro area’s monetary policy to an external requirement – namely an exchange rate target – rather than internal requirements. The euro area was not alone in adopting a flexible exchange rate regime. Most mature economies and some emerging economies also pursue a floating exchange rate regime.

This begs an important question: if you leave it to the market to determine exchange rates, does this mean that there is no role to be played by policy-makers at all? The answer is clearly no. Also countries with a floating exchange rate conduct an exchange rate policy. There are three reasons for this.

First, exchange rate markets are prone to episodes of overshooting and undershooting. Public intervention – in the form of public statements or even outright interventions in FX markets – may thus be warranted.

Second, inadequate macroeconomic or structural policies in a neighbouring country may provoke substantial exchange rate movements that have a detrimental impact on the euro area. Again, public intervention may be warranted.

And third, not all countries have adopted a floating exchange rate regime. These countries may sometimes take steps to prevent the necessary adjustment of their exchange rates, which in turn impacts on economic developments in the euro area. Also here, public intervention may be warranted.

This leads me to another question: does the euro area have the instruments and procedures it needs to effectively implement its exchange rate policy? Here, the answer is clearly yes. The euro area is fully equipped to implement an effective exchange rate policy. Such a policy requires four main ingredients:

first, monitoring and assessing exchange rate markets and developments;

second, discussing market developments with the other major partners;

third, making public statements; and

fourth, intervening in the foreign exchange markets.

In practice, the role of the main actors, typically governments and central banks, depends on the precise architecture of foreign exchange policies, as I will explain. The central bank has to be involved, given its economic and technical expertise, but also because any intervention must be consistent with the monetary policy stance. Finance ministries are often involved because they own the foreign reserves. Moreover, the success of exchange rate policies also depends on supportive domestic policy action. Indeed, regardless of the precise design of competences, all institutional arrangements in this policy field provide for a close interaction between governments and central banks. Let’s now consider these four elements in greater detail.

Monitoring and assessing exchange rate markets and developments. This is not an easy job. Indeed, there is no fully reliable compass for assessing whether an exchange rate is out of line with fundamentals. Moreover, there is no single indicator for exchange rate developments. Rather, the indicator to be chosen depends on what we want to find out. Bilateral exchange rates shed light on the relative movements of the economies of the two countries. Yet for many other questions – such as overall competitiveness developments – we need to have a look at the effective exchange rate. In the euro area, exchange rate developments are regularly monitored and assessed by the ECB. These assessments are shared, as appropriate, with euro area finance ministers and the Commission in the Eurogroup. Since the start of the euro, there have been no disagreements at the technical level either on the assessment or on the action to be taken.

Discussions with the other major partners. This is key, since the effectiveness of policy action critically depends on it being coordinated with other relevant countries. The euro area conducts such discussions at three levels. First, in the context of the G7, the Presidents of the Eurogroup and of the ECB represent the euro area and are closely involved in the relevant deliberations. Second, discussions on exchange rates also take place at the IMF. Here, the potential for the euro area to speak with one voice has not yet been fully exploited. A third forum for discussing exchange rate issues is in the context of bilateral relations. Progress has also been made on this front, notably by setting up a forum for discussion with the Chinese authorities.

Public verbal interventions. Statements of this kind are sometimes made on exchange rates in the context of the G7. Both the Eurogroup and ECB representatives make a major contribution to the preparation of the relevant communiqués. The views expressed by the two representatives have always been consistent and ensured an effective message.

Interventions in foreign exchange markets. The euro area is fully equipped to conduct – if necessary – such interventions. It did so, very effectively, in the autumn of 2000. This instrument is in the hands of the ECB, which can assess when and how to use it in the light of the prevailing market conditions and its monetary policy stance.

To sum up, the euro area has all the necessary instruments to implement an effective exchange rate policy for the euro. Is there scope for improvement? I see three areas where further progress should be made.

First, there is a need for verbal discipline when making statements on exchange rates. Especially in the early years of EMU, public statements on exchange rate developments were too frequently made by individual policy-makers who were not mandated to speak on behalf of the euro area. At times, this has undermined the credibility and effectiveness of the euro area’s exchange rate policy. Only the President of the ECB and the President of the Eurogroup should comment on the exchange rate of the euro. The authorities which are not mandated to speak should heed the adage: ‘silence is golden’.

Second, policy-makers should take into account the potential implications of their domestic policies on exchange rate developments.

Third, the euro area should speak with one voice on exchange rate issues in all international institutions. This holds in particular for the IMF, which since 2007 has been enhancing its surveillance of exchange rate policies. Even though a single currency implies a single exchange rate, the euro area representatives in the IMF Executive Board do not always sing from the same hymn sheet when discussing exchange rate developments in other major countries. It is my conviction that a unified representation of the euro area countries at the IMF would strengthen the exchange rate policy of the euro.

Exchange rate developments during the crisis

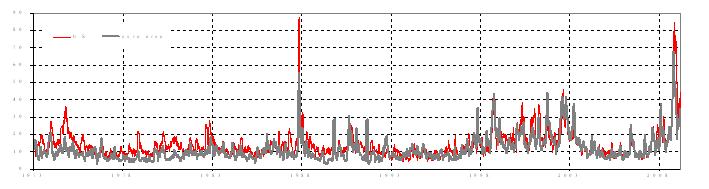

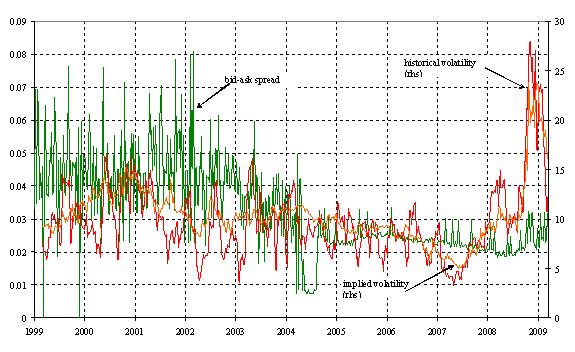

Let me now turn briefly to exchange rate developments since the outbreak of financial turbulence in the summer of 2007. During the last year and a half, foreign exchange markets have witnessed sharp swings in all major bilateral rates. Foreign exchange volatility – both realised and implied – has reached historical levels (see Fig. 1). More recently, the situation seems to have improved as realised volatility eased substantially. Yet the markets’ perception of risk still remains elevated compared with longer term averages. [2]

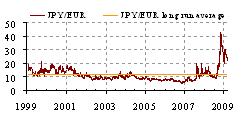

Despite the extremely volatile environment, the spot foreign exchange market seems to be functioning normally. Looking at the euro/dollar bilateral rate, bid-ask spreads (expressed as percentages of the spot rate) have remained largely unaffected by the rise in realised and implied volatilities (see Fig. 3), and broadly in line with their averages since 2004. Nonetheless, some tensions have emerged in the forward foreign exchange market. The US dollar funding needs have led to tensions in global money markets [3] and forced many institutions to convert euros into dollars through FX swaps. In addition, tensions have not remained confined to the shortest horizons, but also spread to longer maturities, as banks have realised that the financial crisis might last longer than anticipated. [4]

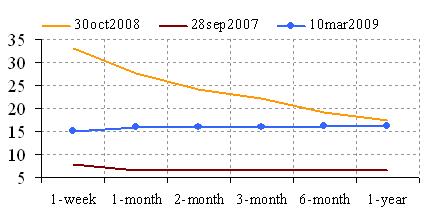

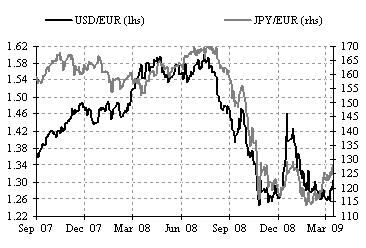

Turning to exchange rate movements, until the summer of 2008, the US dollar weakened against the euro, while the Japanese yen remained broadly stable. This reflected the market perception that the turbulence originated in the United States (see Fig. 4).

Subsequently however, and especially after the Lehman collapse, the euro weakened both against the US dollar and the Japanese yen. The dollar benefited from increasing risk aversion worldwide as well as from temporary factors associated with a widespread shortage of dollar liquidity in financial markets. The yen for its part was boosted by falling policy interest rates worldwide and rising financial volatility. Combined, these factors led to a massive unwinding of the carry trade positions that had been established in the low-volatility environment before the summer of 2007.

On 27 October of last year the G7 issued a joint statement warning about disorderly developments in the foreign exchange of the yen. The Japanese currency stabilised thereafter.

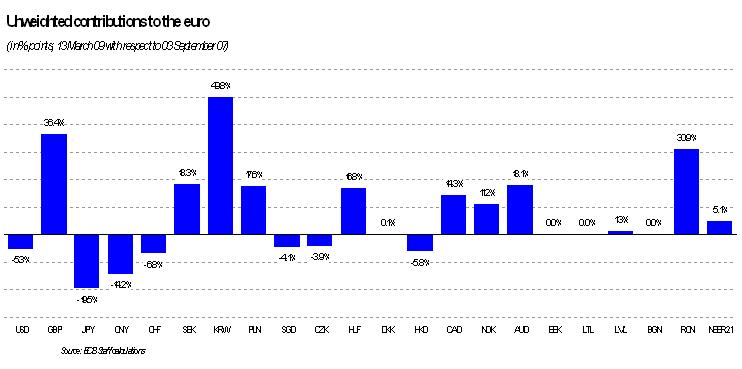

Overall, the euro did not record exceptional movements in nominal effective terms. It appreciated by around 5% [5] between September 2007 and March 2009. This appreciation stemmed from significant gains vis-à-vis the pound sterling and other central and eastern European currencies, and was balanced by the euro’s depreciation against the Japanese yen, the Swiss franc and the US dollar (see Fig. 5). Notably, in its last report on the World Economic Outlook, the IMF considered the real effective exchange rate of the euro to be on the strong side of medium-term fundamentals. [6]

Looking more closely at the euro-dollar exchange rate, some observers have expressed their surprise at the appreciation of the dollar against the euro since mid-2008. Some considered this appreciation to be at odds with the US-related origin of the crisis, especially the weaknesses in the US financial system, and the persistent – albeit gradually improving – US current account deficit.

It is said that the recent dollar appreciation can be traced back in part to the markets' perception of the international status of the dollar, playing the role of safe haven in periods of heightened risk aversion. The strong correlation between rising volatility and US dollar strengthening at a daily frequency points in this direction. The dollar appreciation at the end of 2008 is consistent with a significant rise in net portfolio inflows into the US (in particular for short-term liabilities, including T-bills). [7]

Tensions have also been visible between the currencies of some of the new EU Member States; indeed, the currencies of most of those countries weakened significantly vis-à-vis the euro. Beyond country-specific factors, this reflected the sharp deterioration in economic activity and outlook and, most notably, a reversal of capital flows, as a result of heightened global risk aversion and increased home bias. The functioning of ERM II was overall not adversely impaired, despite the exceptional rise in foreign exchange volatility.

Other dimensions of international monetary coordination

Apart from exchange rate policy, there are other important aspects of international monetary coordination which have come to the fore in the current crisis. On top of their regular exchanges of information and views, central bankers have engaged in unprecedented joint actions to provide liquidity, reduce financial market strains, and counter negative spillover effects on the real economy. For example, on 8 October 2008 the ECB cut interest rates simultaneously with six other central banks, against a backdrop of lower inflationary pressures.

Another example can be found in the area of liquidity management. A key tool in this respect has been the US dollar Term Auction Facility, in which the ECB agreed with the US Federal Reserve to grant loans in dollars to euro area banks. These USD liquidity- providing operations have increased over time in terms of size and number of participants, with a substantial number of central banks now participating. The Eurosystem has also entered into an agreement with the Swiss National Bank in order to facilitate the provision of liquidity denominated in Swiss francs to euro banks. Finally, the Eurosystem has signed agreements with the central banks of several European countries in order to improve the provision of euro liquidity to their banking sectors.

Since the start of the crisis, we have therefore achieved a level of trust and cooperation within the central banking community that some would have considered unthinkable a couple of years ago. As the ECB President put it a couple of weeks ago, global cooperation by central banks is now mirroring the globalisation of finance.

Conclusions

To conclude, the euro area has an exchange rate policy and it has been implementing it over the last ten years, with full cooperation between the authorities in charge, including over the recent months.

International monetary coordination has gone beyond exchange rates, and involved several aspects of central banking, including on one occasion a coordinated interest rate change. Such coordination is aimed at the specific circumstances of the crisis and has helped to restore confidence in financial markets. Having said that, financial and economic conditions do differ across the major countries, and we should not expect that coordination means uniformity of action. Monetary policy in the different areas of the world needs to take into account the specificities related in particular to the shocks that affect the economies and the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. When these specificities are appropriately taken into consideration, the actions of the various monetary authorities appear overall quite homogeneous and consistent.

Appendix:

Figure 1: Developments in volatility

Panel A: realised volatility

Equity markets

euro/dollar exchange rate

Panel B: implied volatilities

|

|

|

Source: Bloomberg, Thomson Financial Datastream and ECB staff calculations.

Note: daily data, % annualised. Last observation 10 March 2009.

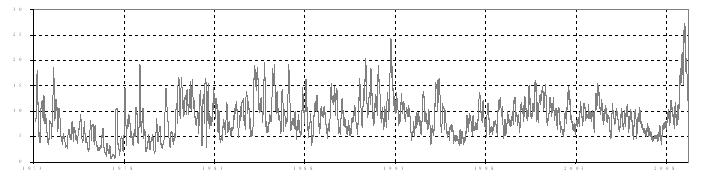

Figure 2: Developments in the term structure of the euro/dollar rate volatility

Note: The chart shows the implied volatilities, at selected dates, taken from at-the-money options on the euro/dollar rates, at the six options’ maturities reported on the x-axis.

Figure 3: euro/dollar rate: bid-ask spread and volatilities

Note: weekly data; last observation is 16 March 2009; the bid-ask spread is expressed as a percentage of the spot rate. Implied and realised volatilities are expressed as percentages in annualised terms.

Figure 4: Developments in main bilateral rates

Note: daily data since 1 Sep. 2007; last observation 17 March 2009.

Figure 5: Changes in the nominal effective and in selected bilateral rates of the euro

-

[1] Article 124.2 TEC.

-

[2] Analysing options’ maturities (see Fig. 2 for the euro/dollar rate) reveals that the increase in the perception of risk was concentrated over the shorter horizons (one to six months), while it remained more contained at the one-year horizon. Since the beginning of 2009, shorter-term expectations of exchange rate volatility have been significantly scaled down, signalling a return to ‘normal’ market conditions.

-

[3] With a widening of the spread between interbank interest rates and overnight index swap (OIS) rates.

-

[4] Empirical evidence (BIS, QR, March 2008) shows that the FX swaps were a key channel through which the financial turmoil spread from money markets to longer term cross-currency swap markets.

-

[5] Vis-à-vis the currencies of 21 important trading partners of the euro area

-

[6] IMF, World Economic Outlook Report (October 2008), p. 54.

-

[7] Source: US Department of the Treasury, Treasury International Capital System, http://www.ustreas.gov/tic/

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts