- Speech

- Helsinki, 2 July 2019

Monetary Policy and Below-Target Inflation

Speech by Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Bank of Finland conference on Monetary Policy and Future of EMU

I would like to thank the Bank of Finland for inviting me to speak at this conference in Helsinki today.[1]

In my contribution, I wish to share some thoughts on the conduct of monetary policy in a low-inflation environment. This is a global topic that generates similar challenges for most of the central banks represented at this event. To a significant extent, this sequence of low inflation rates reflects the prolonged adjustment dynamics that characterise the aftermath of a major global financial crisis, together with a substantial downward shift in the realisation of shocks to inflation that we have observed in recent years. At the same time, regardless of the underlying origins of the current low inflation environment, some observers may be tempted to query whether and how central banks will meet their inflation objectives, especially under conditions in which monetary accommodation is already quite extensive.

To address these concerns in respect of the euro area, I will demonstrate the effectiveness of the policy instruments that we have deployed to ensure that inflation climbs to meet our objective over the medium term. As will be explained in the analysis, my assessment is that the evidence shows that our package of monetary policy measures has been an effective response to the environment that the ECB has faced in recent years. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the policy toolkit means that we can add further monetary accommodation if it is required to deliver our objective.

Finally, especially when inflation deviates from its objective for an extended period, central banks ‒ including the ECB ‒ should adopt clear communication strategies that leave no doubt about their absolute commitment to meeting the inflation objective over the medium term.

The ECB’s instruments and tools

Excellent accounts of the history of ECB monetary policy are provided by Hutchinson and Smets (2017), Hartmann and Smets (2019) and Rostagno et al. (forthcoming). As a summary device, Chart 1 shows some key interest rates and developments in excess liquidity in recent years. The chart underlines the primary role of the deposit facility rate – which has been in negative territory since 2014 – in anchoring the key EONIA market interest rate in a world in which the money market operates in conditions of excess liquidity. From mid-2014 onwards, net liquidity provision from refinancing operations and asset purchases has markedly increased. In part, this expansion of liquidity provision depended on banks choosing to take up funding support in refinancing operations, especially conventional longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) and, more recently, targeted LTROs (TLTROs). However, the expansion during 2014-18 was dominated by our asset purchase programme (APP).

EONIA, key ECB interest rates and excess liquidity

(lhs: € bn; rhs: percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB.Notes: Daily data. Excess liquidity is computed as the sum of credit institutions’ central bank liquidity holdings with the Eurosystem in their current accounts and deposit facility minus their reserve requirements. EONIA stands for the euro overnight unsecured interbank rate, DFR for the deposit facility rate and MLF for the marginal lending facility.Last observation: 25 June 2019.

In recent years, the ECB has deployed an innovative, multi-pronged approach in the design of its policy stance. While it is always possible to envisage a wider range of instruments, the current policy mix includes four elements: (i) pushing the policy rate into negative territory, (ii) forward guidance on the future policy path, (iii) the APP, and (iv) TLTROs. Importantly, these measures work as a package, with significant complementarities across the different instruments.

I will outline the effectiveness of these four measures. Doing so shows the capacity of our policy framework to provide the monetary accommodation required to return inflation to the medium-term goal, even when the policy rate is no longer in conventional positive territory. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these tools also provides leeway for further easing if it is required.

Negative policy rate (deposit facility rate)

The 2014 decision by the ECB to push the relevant policy rate (the deposit facility rate) into negative territory was a crucial policy innovation. Subsequent cuts have taken the deposit facility rate to its current level of minus 40 basis points.

An important mechanism that reinforces the impact of negative interest rates relates to the way expectations about the future path of monetary policy are reflected in market interest rates. [2] At any point in time, a wide range of future interest rate paths is conceivable and market participants assign probabilities to different parts of this distribution. The yield and forward curves observed in the market are the probability-weighted averages of these possible paths, aggregated across market participants.

A perceived binding lower bound on monetary policy rates skews the predictive distribution upward, since it truncates the distribution of conceivable future short-term rates from below: as the overnight interest rate reaches the lower bound, interest rate paths that would have embodied expectations of a further cut at a higher level of the actual overnight rate are, by definition, eliminated from the set of conceivable outcomes; conversely, rates above the lower bound receive a higher relative weight and the expected value of interest rates is mechanically pushed up.[3]

While longer-term yields are likely to decline even as the central bank cuts the short-term rate towards its lower bound, the truncated asymmetric distribution of expected future short-term rates means that they decline by less than they would away from the lower bound. The resultant tightening bias, in turn, can be quite costly, since it tends to arise in situations of strong and persistent disinflationary pressures and in the wake of a previous sequence of sizeable rate cuts.

A policy of negative interest rates mitigates this tightening bias. In particular, the observation that a central bank is prepared to take interest rates to levels below zero induces a re-evaluation of technical feasibility constraints. A salient feature of this re-evaluation is the disappearance of the qualifier “zero” in the economic debate on lower bound constraints. Via this re-evaluation, negative rates loosen the perceived lower bound on the future distribution of short-term interest rates.[4]

Through this mechanism, negative interest rates have a marked impact on transmission, particularly in the euro area, as they push down the short and medium segment of the risk-free curve, which for the most part is the segment of the curve that determines the pricing of loans to non-financial corporations. It follows that control of this segment of the curve directly influences the level of lending rates.

To illustrate the effectiveness of negative policy rates, ECB staff undertook a counterfactual exercise. They constructed the forward curve that would prevail in a scenario without either the negative interest rate policy or the forward guidance on the future path of the policy rates. As shown in Chart 2, the forward curve derived from the overnight index swap curve would be pinned at a higher level and would be distinctly steeper (the dashed blue line on the right) than the forward curve that we observe today (the red curve).

Expectations of future short-term rates, observed and counterfactual under no NIRP

(percentage per annum)

Sources: Bloomberg, Rostagno et al. (2019).Notes: The chart shows the evolution of the OIS forward curve from pre-policy package (dashed black line) to post-policy package (red line), together with risk neutral option-implied distributions (EURIBOR 3m – spread adjusted), as well as a shifted counterfactual forward curve (dashed blue line) and the risk-neutral option-implied distribution. The counterfactual distribution and forward curve is constructed by anchoring the current distribution at zero and subsequently assuming that without NIRP, all probability mass that is observed below zero after shifting would proportionally redistribute to zero.

While this mainly serves as an illustration, as it is based on a number of assumptions and input parameters, it is indicative of the sort of tighter interest rate constellations that the euro area economy would face in the absence of this important policy tool. Our negative policy rate thus contributes substantially to providing monetary accommodation. At the same time, it is also clear that there may be negative side effects.[5] Accordingly, the Governing Council will continue to assess the case for mitigating measures, which is especially relevant if further rate cuts are envisaged.

Forward guidance on interest rates

Our interest rate forward guidance with its state-contingent and date-based legs has become the principal tool for adjusting the monetary policy stance, especially following the end of net asset purchases. The state-contingent leg expresses the anchor of our policy-setting expectations: policy rates will not be raised until we are sufficiently confident that inflation will reach levels that we consider most consistent with the ECB’s price stability objective. This, in turn, allows interest rate expectations to adjust dynamically in a data-dependent manner, which results in automatic easing if the convergence path is delayed.

Through the date-based leg, the Governing Council affects interest rate expectations by expressing its views about the rate path in the near term that, given the outlook for inflation, is most conducive to reaching the objective over the medium term. This removes unnecessary uncertainty about the policy orientation over horizons that are not stretching too far into the future and prevents an unwanted weakening of the monetary policy stimulus.

The evidence shows that our enhanced forward guidance has been effective. The state-contingent element is clearly understood by investors and is influencing their expectations. Since the second half of 2018, when we enhanced our forward guidance on interest rates (and especially since the monetary policy meeting of the Governing Council in March 2019), the reassessment by investors of information regarding the outlook has led them to expect a somewhat longer horizon over which rates are more likely than not to remain unchanged. Accordingly, the EONIA forward curve has shifted down substantially over recent months (see Chart 3).

EONIA, forward curve estimates from OIS

(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.Latest observation: 24 June 2019.

In light of this endogenous adaptability of the state-contingent leg through investor behaviour, occasional gaps may emerge vis-à-vis the date-based leg, since the latter can only be recalibrated at each Governing Council monetary policy meeting. In March and June 2019, the Governing Council assessed that the risks to price stability warranted a recalibration of the date-based leg, thereby conveying the Governing Council’s updated assessment of the direction that the ECB’s key interest rates will have to follow. The Governing Council now expects to keep policy rates unchanged “at least through the first half of 2020”.

It should be fully understood that a change to the date-based leg is not intended to ratify market views. Rather, it provides information on the Governing Council’s assessment of the rate path that, given the evolving state of the economy, we view as the likeliest to be realised. Finally, the inherent flexibility in our forward guidance framework always allows for additional enhancements to ensure that inflation remains on a sustained adjustment path.

APP

The significant stock of assets purchased through the APP and the subsequent reinvestments once net purchases ended in December 2018 have been providing substantial monetary accommodation to the euro area. My colleague Benoît Cœuré recently provided a thorough assessment and Chart 4 and Chart 5 illustrate the contribution of the APP to the easing of financial conditions through the reduction of yields.[6] According to those estimates, after the last recalibration of the APP in June 2018, the ten-year bond yield would have been around 95 basis points higher in the absence of the APP. Moreover, this impact is quite persistent.

Asset purchases work through a variety of mechanisms. Of particular importance is the duration channel. By absorbing duration risk from the market, investors require less risk compensation, which pushes down term premia and yields. The duration channel is complemented by the signalling channel through which asset purchases can affect the expected path of short-term policy rates.[7] Importantly, the bonds we have purchased will remain on our balance sheet for a long time and we continue to reinvest maturing principals (Chart 4). A meaningful stock effect will therefore continue to prevail and will exert substantial downward pressure on yields (Chart 5), particularly at the longer end of the curve.

The reinvestment horizon is linked to the forward guidance on policy rates: we now say that we will “continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the asset purchase programme for an extended period of time past the date when we start raising the key ECB interest rates […]”. This means that any recalibration of the date-based leg of forward guidance by construction extends the period over which investors expect the ECB to continue reinvesting in full; this prolongs the favourable liquidity conditions and reinforces the downward effect of our rate forward guidance on long-term rates by suppressing term premia (see Chart 5).

Projected evolution of the PSPP portfolio of the four largest euro area countries in maturity-adjusted terms

(€bn ten-year equivalents)

Source: Based on Eser, Lemke, Nyholm, Radde, Vladu (2019).Notes: For selected dates, corresponding to recalibrations of the APP, the figure shows the projected evolution of the government bond holdings for the four largest euro area countries in terms of ten-year equivalents.

Estimated effect of APP recalibration vintages on euro area ten-year term premium

(basis points)

Source: Based on Eser, Lemke, Nyholm, Radde, Vladu (2019).Notes: For selected dates, corresponding to recalibrations of the APP, the figure shows the impact of the APP through the duration channel on the term premium component of the ten-year sovereign bond yield (averaged across the four largest euro area countries) over time. Estimates are based on a no-arbitrage term structure model incorporating the relative bond supply held by price-sensitive investors (“free-float”).

If warranted by our policy assessment, net purchases under the APP could be restarted in the future.[8] In the event of any resumption of net purchases, associated revisions to the framework of forward guidance would have to be considered in order to make sure that the different instruments continue to be tightly linked and that their synergies are maximised.

TLTROs

The Governing Council recently decided to start a third series of TLTROs (TLTRO III) to help preserve favourable bank lending conditions and support the smooth transmission of monetary policy. The generous borrowing conditions offered to banks should not only provide a backstop to the banking system but also lower aggregate funding costs, which contributes to the overall accommodative monetary policy stance.

The funding cost relief is direct for those banks that switch from more expensive options to TLTRO financing. However, there is also an indirect channel that benefits the entire banking system: while looking ahead banks will have to step up their issuance in order to satisfy regulatory requirements, the TLTRO programme will help avoid cliff effects by allowing banks drawing TLTRO funds to cancel or postpone plans to issue bonds in the market. This reduction in the supply of securities relative to what we would see in the absence of TLTRO III creates a scarcity channel that puts further downward pressure on bank bond yields, resulting in funding cost relief across the board. The upshot of cheaper bank funding is higher credit volumes and lower lending rates to the wider economy via the bank lending channel.[9]

Impact of TLTRO on lending rates (upper chart) and lending volumes (lower chart)

(percentage points, deviations from September 2014)

Sources: ECB iMIR and ECB calculations.Notes: NFC lending rates are on outstanding loans to non-financial corporations weighted by volume. The chart shows average rates across bidders and non-bidders in deviation from rates in September 2014. “Vulnerable countries” are Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovenia. “Other countries” are all the remaining euro area countries.

Impact of TLTRO on lending volumes

(notional stock, September 2014=1)

Sources: ECB iBSI and ECB calculations.Notes: The chart shows the notional stock of loans to NFCs across bidders and non-bidders relative to September 2014. “Vulnerable countries” are Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal and Slovenia. “Other countries” are all the remaining euro area countries.

In fact, our experience with previous TLTROs (TLTRO I and II) was that these operations had a significant effect on funding costs, particularly in more vulnerable euro area countries. Moreover, the lower funding costs were passed through to customers. Particularly in vulnerable countries, banks that participated in TLTROs cut their lending rates by more than their non-participating peers (see Chart 6).

The policy package

In assessing the impact of our policy package, we must also take into account that the instruments were designed to be complementary and mutually reinforcing. Overall, the transmission of our suite of measures to the financial system has been very effective. This is in no small part due to the strong complementarities between instruments, which ensure that all segments of the yield curve are influenced, thereby easing financial conditions more broadly (see Chart 7).

Let me give two examples to illustrate the role played by complementarities in our policy design. First, the negative interest rate policy has supported the portfolio rebalancing channel of the APP by encouraging banks to lend to the broad economy instead of holding onto liquidity.[10] At the same time, the extra liquidity from the APP has dampened volatility at the short end of the curve.

Second, the APP and its reinvestments have supported our enhanced forward guidance via the signalling channel.[11] Asset purchases provide a strong signal that policy rates will remain low for an extended period of time. This effect is reinforced by the sequencing of our instruments, which is embedded in the structure of our forward guidance. At the same time, our forward guidance on rates reinforces the APP and reinvestments, since it anchors the short end of the risk-free curve and thereby ensures that the stimulus from the APP and the reinvestments is not offset.

Impact of ECB non-standard measures on the term structure of interest rates 2014-18

(percentage points per annum)

Source: Rostagno et al. (2019).

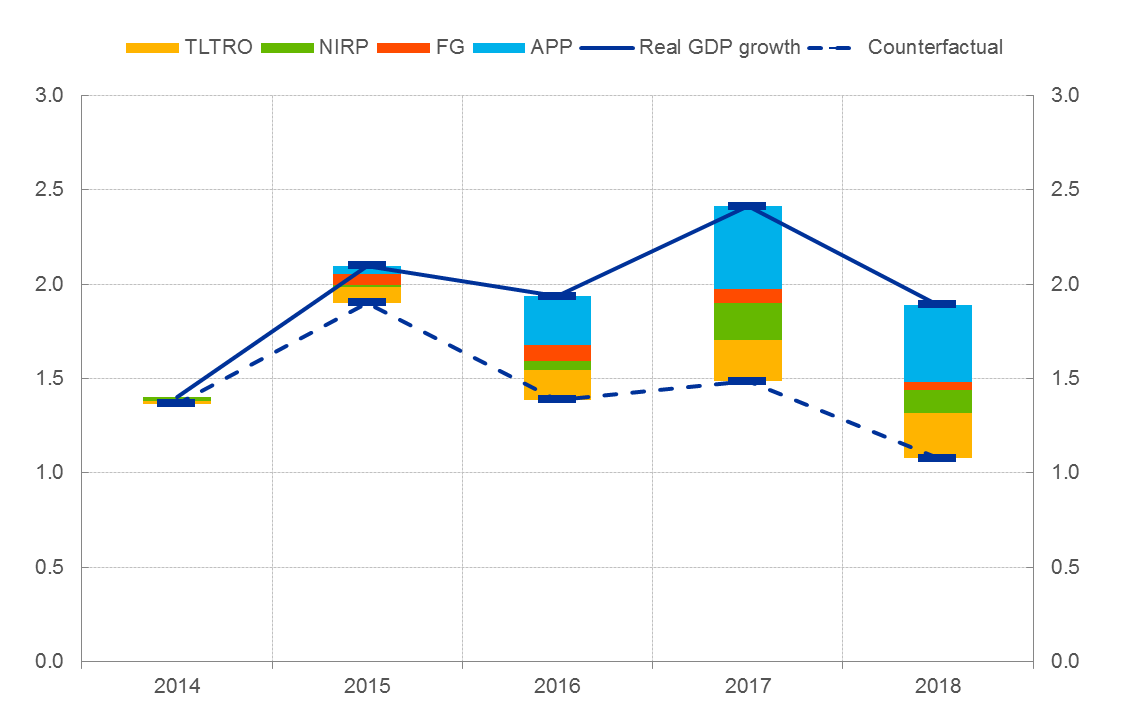

The improved financing conditions have made a considerable contribution to the macroeconomic performance of the euro area. A counterfactual exercise undertaken by ECB staff shows that growth and inflation would have been notably lower in the absence of our non-standard measures (see Chart 8 and Chart 9). [12]

Contribution of ECB non-standard measures to real GDP growth 2014-18

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Source: Rostagno et al. (2019).

Contribution of ECB non-standard measures to HICP inflation 2014-18

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Source: Rostagno et al. (2019).

That said, as the Governing Council has emphasised many times, in order to reap the full benefits from our monetary policy measures, it is important that other policy areas make a more decisive contribution. In particular, growth-enhancing and vulnerability-reducing measures would combine to improve confidence in the long-term potential of the euro area economy, which is a central factor in determining assessments of steady-state real interest rates. Moreover, the aggregate cyclical stance of fiscal policy plays an important role in determining the amplitude and duration of economic fluctuations. As noted by President Draghi in his Sintra speech, a cyclically-appropriate aggregate fiscal stance may be more easily achieved through a well-designed central fiscal capacity.

Let me now turn to the importance of effective communication in maintaining focus on the inflation objective, especially during phases of extended deviations.

Central bank communication

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union establishes price stability as the primary objective of the ECB. The ECB strategy makes the primary objective of price stability operational through the medium-term orientation of monetary policy. This medium-term orientation provides the necessary flexibility to combat excessive volatility in output and inflation in responding to shocks.

The medium term refers to a time span that is long enough to be consistent with a central bank’s capacity to control inflation, taking into account the typical transmission lag. The horizon should be short enough for the public to be able to assess the performance of the central bank in delivering its inflation goal. At the same time, too long a span of time obstructs accountability.

However, the definition of the medium term cannot be reduced to a fixed interval: it must be interpreted as state-dependent. A demand shock that pushes inflation away from its desired level and output away from potential in the same direction calls for a policy horizon as short as the typical transmission lag: the policy response to such a shock is faster and stronger than otherwise. By contrast, if the economy is hit by persistent supply-side shocks, for example, the medium-term interval can stretch well beyond the standard transmission lag of monetary policy. Furthermore, a medium-term orientation implies that inflation can deviate from our aim in both directions, so long as the path of inflation can be expected to converge back to the objective.

Maintaining a medium-term orientation is facilitated by a credible commitment to the inflation goal, such that inflation expectations remain well anchored even during a prolonged phase of inflation deviation. One piece of evidence on how expectations are formed is provided by a recent special questionnaire in the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF), in which participants were asked about the factors that inform their longer-term expectations, meaning four or five years ahead.[13] The responses indicated that trends in inflation emerged as a substantial driving factor, and it is fair to assume that such trends build to a very large extent on historical and thereby backward-looking data on actual inflation. However, the ECB’s inflation objective has remained the most important factor informing the longer-term expectations of SPF participants. Given that trends in actual inflation have clearly weakened in recent years, the role of the inflation objective as an anchor of expectations has been brought more strongly to the fore.

One sign of this is the looser association in recent times of longer-term inflation expectations with the average of actual inflation calculated cumulatively over the history of monetary union (Chart 10). While this average ‒ and the same holds for averages taken over shorter time spans ‒ has come down over the period of low inflation, longer-term expectations have declined to a much lesser extent. This suggests that participants have not been overly extrapolative in forming their expectations about inflation.

Euro area HICP inflation and inflation expectations

(y-o-y percentage change)

Sources: ECB, Consensus Economics, Thomson Reuters, ECB calculations.Note: BEIR (break-even inflation rate) is defined as the yield spread between nominal and inflation-linked bonds. ILS stands for inflation-linked swaps, a financial asset which hedges against the risk of inflation. SPF (Survey of Professional Forecasters) and Consensus Economics denote the expected long-term inflation expectations (in five years and in six to ten years, respectively) as inferred from the average point estimate of both surveys. All series except the survey series are quarterly averages.Last observation: 2019 Q2.

Maintaining the medium-term inflation goal as the guideline for households, firms and market participants in forming expectations also requires a consistent communication strategy, especially when the near-term track record of inflation outcomes has deviated from the objective. In part, this communication strategy is anchored by our forward guidance on policy measures, so that everyone understands that the conditional future policy path supports convergence to the aim. It is also supported by demonstrating agility, with the central bank communicating that it stands ready to adjust its policy measures at any time to avoid undue delay in returning to the inflation goal and combat any adverse shock to inflation dynamics.

It is also crucial to the successful anchoring of inflation expectations that the central bank shows it is a learning organisation that is committed in its search for the most effective policy tools in delivering its mandate. This general principle is especially relevant during phases when economic and financial conditions pose new challenges and require novel policy responses. Whether through innovations such as the Outright Monetary Transactions programme during the sovereign debt crisis or through the package of innovative policy measures that have been launched in recent years, the ECB has shown itself to be creative and proactive in responding to new challenges.

In common with other central banks, the ECB must always be open to new ideas and new methods, drawing from internal and external research and examples of best practice from around the world. Of course, not all new ideas withstand sustained scrutiny, but the exploration of new methods and formulations is essential for successful performance. For instance, albeit with an orientation to the specific conditions of the US economy, the academic contributions to the June conference at the Federal Reserve of Chicago show the vibrancy of current international research on meeting the challenges of low inflation. Some of these themes were also identified in President Draghi’s recent Sintra speech. There should be no doubt that the ECB is committed to ensuring that our monetary policy is built on frontier-level and robust theoretical and empirical analysis.

Conclusions

Together with the extended nature of macro-financial adjustment in the wake of a major financial crisis, we have seen a substantial downward shift in the realisation of shocks to inflation in recent years. In the context of the euro area, the ECB has been active and creative in deploying non-standard measures, in addition to extending the range for the policy rate into negative territory. Our assessment is that this policy package has been effective and further easing can be provided if required to deliver our mandate.

At the same time, an extended phase of below-target inflation poses a communication challenge in maintaining focus on the medium-term inflation goal. It is obvious that it is easier to demonstrate commitment to the target if the actual track record of inflation outcomes corresponds more closely to the declared objective. Accordingly, it is essential that a central bank shows consistency in its monetary policy decisions by proactively responding to shocks that might delay convergence to the target or move inflation dynamics in an adverse direction. To this end, especially in a world of non-standard measures and an essential role for forward guidance, it is also vital that a central bank demonstrates that it is always seeking the most effective methods to deliver on its mandate.

References

Albertazzi, Ugo; Altavilla, Carlo; Boucinha, Miguel and Di Maggio, Marco (2018), “The Incentive Channel of Monetary Policy: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Liquidity Operations”, mimeo, First Annual RTF Workshop, Frankfurt am Main.

Altavilla, Carlo; Canova, Fabio and Ciccarelli, Matteo (2016), “Mending the Broken Link: Heterogeneous Bank Lending and Monetary Policy Pass-Through”, Journal of Monetary Economics, forthcoming.

Benetton, Matteo and Fantino, Dadvide (2018), “Competition and the Pass-Through of Unconventional Monetary Policy: Evidence From TLTROs”, Banca d’Italia Working Paper No 1187.

Bottero, Margherita; Minoiu, Cameli; Peydro, José-Louis;, Presbitero, Andrea and Sette, Enrico (2019), “Negative Monetary Policy Rates and Portfolio Rebalancing: Evidence from Credit Register Data,” IMF Working Paper WP/19/44.

Brunnermeier, Markus and Koby, Yann (2018), “The reversal interest rate”, NBER Working Papers 25406, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cœuré, Benoît (2019), “The effects of APP reinvestments on euro area bond markets”, closing remarks at the ECB’s Bond Market Contact Group meeting, 12 June 2019.

Demiralp, Selva; Eisenschmidt, Jens and Vlassopoulos, Thomas (2019), “Negative interest rates, excess liquidity and retail deposits: banks’ reaction to unconventional monetary policy in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2283, ECB.

Draghi, Mario (2019), “Twenty Years of the ECB’s monetary policy”, ECB Forum on Central Banking, Sintra, 18 June 2019.

ECB (2019a), “Twenty years of the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1.

ECB (2019b) “Taking stock of the Eurosystem’s asset purchase programme after the end of net asset purchases”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

Eser, Fabian; Lemke, Wolfgang; Nyholm, Ken; Radde, Sören and Vladu, Andreea Liliana (2019), “Tracing the impact of the ECB’s asset purchase programme on the yield curve”, Working Paper Series, ECB, forthcoming.

Hartmann, Philipp and Smets, Frank (2019), “The first twenty years of the European Central Bank: monetary policy”, Working Paper Series, No 2219, ECB.

Hutchinson, John and Smets, Frank (2017), “Monetary Policy in Uncertain Times: ECB Monetary Policy Since June 2014”, The Manchester School, Vol. 85.

Lemke, Wolfgang and Vladu, Andreea Liliana (2017), “Below the zero lower bound: a shadow-rate term structure model for the euro area,” Working Paper Series, No 1991, ECB.

Rostagno, Massimo; Altavilla, Carlo; Carboni, Giacomo; Lemke, Wolfgang; Motto, Roberto; Saint-Guilhem, Arthur and Yiangou, Jonathan (2019), “A Tale of two Decades: The ECB’s Monetary Policy at 20”, forthcoming.

Ruge-Murcia, Francisco (2006), “The expectations hypothesis of the term structure when interest rates are close to zero”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 53(7), pages 1409-1424.

- [1]I would like to thank John Hutchinson for his contribution to this speech.

- [2]Another important mechanism through which negative interest rates provide stimulus is by enhancing the velocity of circulation of bank reserves.

- [3]For a formal documentation of the bias arising under the zero lower bound, see Ruge-Murcia (2006).

- [4]For a formal treatment of how a relaxation of the lower bound affects future rate distributions and the yield curve, see Lemke. and Vladu (2017). For an example of a study that uses loan-level data to confirm that NIRP works through a portfolio rebalancing channel and also incentives banks to rebalance their portfolios from liquid assets to credit, see Bottero, Minoiu, Peydro, Polo, Presbitero and Sette (2019).

- [5]For example, see Brunnermeier and Koby (2018).

- [6]See Cœuré (2019).

- [7]For a more in-depth discussion of those channels and an empirical assessment, see ECB (2019b).

- [8]See Draghi (2019).

- [9]For some examples, see the following studies: Albertazzi, Altavilla, Boucinha, and Di Maggio (2018); Altavilla, Canova, and Ciccarelli (2016); and Benetton and Fantino (2018).

- [10]See Demiralp, Eisenschmidt, and Vlassopoulos (2019).

- [11]See Altavilla, Carboni, and Motto (2015).

- [12]The macroeconomic impact reported in Rostagno et al. (2019) is broadly comparable with that in ECB (2019b) over a comparable period.

- [13]For more details, see ECB (2019a).

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts