Overview

The near-term outlook for economic activity in the euro area has sharply deteriorated and is surrounded by very high uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic, which started in China and has recently spread to Italy and to other countries, implies a significant negative shock, which is expected to have a strong adverse impact on euro area activity, at least in the short term, affecting both supply and demand. The deterioration of activity in China and in other affected countries implies weaker euro area export growth and disruptions to global supply chains. The recent sharp corrections in global stock markets are expected to lead to a deterioration in consumer and business confidence. Moreover, strict containment measures will adversely affect the supply side of the economy and also have significant negative implications for demand, affecting certain sectors disproportionately (e.g. tourism, transport, and recreational and cultural services).

The full impact of the COVID-19 shock is, at this stage, very difficult to assess. Staff finalised the baseline euro area projections on 28 February, taking into account information available at that point and on the basis of assumptions with a cut-off date of 18 February. However, information that has become available in the course of March regarding a faster spread of COVID-19 in the euro area and globally, which was accompanied by strong declines in financial markets and oil prices, is not captured in the projections. As a result, the projections are surrounded by notable downside risks, especially in the short term. Furthermore, the extent, severity and duration of lockdown measures compound the downside risks to the near-term outlook.

Although the duration and severity of the COVID-19 outbreak is surrounded by high uncertainty, the baseline assumes that the virus will be contained in the next few months, allowing for a normalisation of growth in the second half of 2020. Beyond the near term, the very favourable financing conditions, some dissipation of global uncertainty, the associated gradual recovery in foreign demand and noticeable fiscal easing, should all support a recovery in growth. Overall, real GDP growth is projected to decline to 0.8% in 2020 from 1.2% in 2019, before increasing to 1.3% in 2021 and 1.4% in 2022. Compared with the December 2019 projections, growth has been revised down by 0.3 percentage points for 2020 and by 0.1 percentage points for 2021, mainly on account of the COVID-19 outbreak.

HICP inflation is expected to decline slightly from 1.2% in 2019 to 1.1% in 2020 and to rise over the remainder of the projection horizon to 1.6% by 2022. The dip in the profile of HICP inflation in the course of 2020 reflects negative rates in HICP energy inflation on account of declines in oil prices up to the cut-off date, which partly stemmed from concerns about the global outlook due to COVID-19. Beyond the impact on the oil price, the implications of the spread of COVID-19 for inflation are surrounded by considerable uncertainty. It is assumed in the projections that the downward pressures on prices related to weaker demand in 2020 are largely offset by upward effects related to supply disruptions, although this assessment is subject to clear downside risks. Over the medium term, HICP inflation excluding energy and food should be supported by the gradual recovery in activity, relatively robust wage growth in a context of tight labour markets, and recovering profit margins. In addition, rising non-energy commodity prices and import prices should contribute to the increase in HICP inflation excluding energy and food. Compared with the December 2019 projections, the projection for HICP inflation is unrevised.[1]

In the context of the high uncertainty surrounding the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, related model-based adverse scenarios have been prepared (see Box 3). The materialisation of these scenarios would imply, compared with the March 2020 projections, lower GDP growth in 2020 between 0.6 percentage points and 1.4 percentage points, while inflation would be lower between 0.2 percentage points and 0.8 percentage points, depending on the severity of the scenario and the model used. It should be noted that in these scenarios, monetary and fiscal policy do not react. Including such policy reactions could significantly mitigate the effects in these scenarios.

1 Real economy

Euro area real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2019 came in at 0.1%, weaker than had been expected in the December 2019 projections. Beyond temporary factors, such as calendar effects related to the timing of the Christmas holidays and strikes in France, the weaker outturn mainly reflected continued underlying weakness in the manufacturing sector likely due to adverse global factors.

Chart 1

Euro area real GDP

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, seasonally and working day-adjusted quarterly data)

Notes: The ranges shown around the projections are based on the differences between actual outcomes and previous projections carried out over a number of years. The width of the ranges is twice the average absolute value of these differences. The method used for calculating the ranges, involving a correction for exceptional events, is documented in “New procedure for constructing Eurosystem and ECB staff projection ranges”, ECB, December 2009, available on the ECB’s website.

Sentiment indicators across sectors – based on surveys conducted before the recent outbreak of COVID-19 in the euro area – had improved in January and February 2020, likely reflecting some dissipation of global uncertainties. The Economic Sentiment Indicator compiled by the European Commission continued to improve, from a level well below its long-term average to a level close to it. Consumer confidence improved markedly in February, after being flat in January, and climbed above its long-term average. The Purchasing Managers’ Indices have also improved in the first two months of 2020, with manufacturing data rising to slightly below the growth threshold of 50, while the indices for the services and construction sectors remain above 50. Overall, the latest indicators, based on surveys conducted before the recent outbreak of COVID-19 in the euro area, would have suggested a small pick-up in growth in the first half of 2020.

Despite the rather favourable signals from sentiment indicators available at the end of February, the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak implies very weak growth in the near term. Lower import demand from China, amplified by global supply chain disruptions, and, importantly, the more recent outbreaks in Italy and other euro area countries are assumed to continue over the coming months before the virus is contained. As a result, activity in the first half of 2020 will be affected not only because of the impact of strict containment measures (such as temporary factory closures, travel restrictions, and the cancellation of mass gatherings and large-scale events) but also because of an expected adverse impact on confidence. From a sectoral perspective, services -- especially tourism, transport and recreational and cultural services -- are expected to be particularly affected. Continued underlying weakness in manufacturing, as seen in late 2019, will also hold back activity in early 2020. Growth is expected to recover from the second half of 2020 onwards, based on the assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic is contained.

Over the medium term, the baseline assumes a gradual dissipation of global headwinds, allowing the fundamental factors supporting euro area expansion to regain traction (see Chart 1 and Table 1). In particular, the baseline assumes an agreement on future EU-UK trade relations by the end of 2020 and no further trade protectionist measures globally (beyond those already announced). Thus, the current level of global policy uncertainty will gradually decline, allowing the fundamentals driving growth to regain traction and support activity in 2021 and 2022. Financing conditions are expected to remain very accommodative and the ECB’s monetary policy measures will continue to be transmitted to the economy. More specifically, the technical assumptions imply that nominal long-term interest rates increase only modestly from their current record low levels over the projection horizon. Growth in private consumption and residential investment should also benefit from relatively robust wage growth. Euro area exports are expected to benefit from the projected recovery in foreign demand. Finally, the fiscal stance is expected to loosen in the period 2020-21 (see Section 3).

Nevertheless, the fading out of some tailwinds should reduce growth momentum towards the end of the projection horizon. Labour force growth is expected to slow, mostly reflecting labour supply constraints, partly related to demographic factors, in some countries. Moreover, after several years of expansionary fiscal policy, the euro area fiscal stance is expected to turn broadly neutral in 2022.

Table 1

Macroeconomic projections for the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Note: Real GDP and components, unit labour costs, compensation per employee and labour productivity refer to seasonally and working day-adjusted data.

1) The ranges shown around the projections are based on the differences between actual outcomes and previous projections carried out over a number of years. The width of the ranges is twice the average absolute value of these differences. The method used for calculating the ranges, involving a correction for exceptional events, is documented in New procedure for constructing Eurosystem and ECB staff projection ranges, ECB, December 2009, available on the ECB’s website.

2) Including intra-euro area trade.

3) The sub-index is based on estimates of actual impacts of indirect taxes. This may differ from Eurostat data, which assume a full and immediate pass-through of tax impacts to the HICP.

4) Calculated as the government balance net of transitory effects of the economic cycle and temporary measures taken by governments.

Turning in more detail to the components of GDP growth, private consumption growth is expected to be relatively resilient over the projection horizon. In the short term, despite continued growth in real wages and the positive effects of fiscal loosening in some countries, the expected impact of COVID-19 and a likely drop in confidence should lead to a pick-up in the saving ratio and therefore to a weaker outlook for private consumption than previously expected. Over the projection horizon, private consumption growth should be supported by favourable financing conditions and ongoing wage growth. Nominal bank lending rates are projected to decline slightly further in 2020, before increasing modestly in 2021-22. Given that bank lending rates and bank lending volumes to households are projected to increase only moderately in the coming years, gross interest payments are expected to remain at low levels and, therefore, continue to support private consumption.

Box 1

Technical assumptions about interest rates, exchange rates and commodity prices

Compared with the December 2019 projections, the technical assumptions include lower oil prices, a weaker effective exchange rate and lower long-term interest rates. The technical assumptions about interest rates and commodity prices are based on market expectations, with a cut-off date of 18 February 2020. Short-term rates refer to the three-month EURIBOR, with market expectations derived from futures rates. The methodology gives an average level for these short-term interest rates of -0.4% over the entire projection horizon. The market expectations for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields imply an average level of 0.1% for 2020, 0.2% for 2021 and 0.3% for 2022.[2] Compared with the December 2019 projections, market expectations for short-term interest rates have been revised down by about 10 basis points for 2022, while euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields have been revised down by around 20 basis points for 2020 to 2022.

As regards commodity prices, on the basis of the path implied by futures markets by taking the average of the two-week period ending on the cut-off date of 18 February 2020, the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil is assumed to decline from USD 64.0 in 2019 to USD 56.4 in 2020 and to ease to USD 55.4 by 2022. This path implies that, in comparison with the December 2019 projections, oil prices in US dollars are lower over the entire horizon. The prices of non-energy commodities in US dollars are estimated to have declined in 2019 but are assumed to rebound over the subsequent years.

Bilateral exchange rates are assumed to remain unchanged over the projection horizon at the average levels prevailing in the two-week period ending on the cut-off date of 18 February 2020. This implies an average exchange rate of USD 1.09 per euro over the period 2020-22, which is slightly lower than in the December 2019 projections. The effective exchange rate of the euro (against 38 trading partners) has depreciated by 1.1% since the December 2019 projections. The euro’s weakness is broad-based, as it depreciated against all major currencies.

Technical assumptions

Recent market developments since the cut-off date would imply a significant revision of the technical assumptions: the euro has appreciated while financial markets and oil prices have strongly declined, reflecting, inter alia, the spread of COVID-19. The euro has lately strengthened vis-à-vis the US dollar, following the unexpected rate cut by the Federal Reserve; in sovereign debt markets, yields for certain debt instruments (such as ten-year German government bonds) fell strongly reflecting a combination of growth concerns and flight to safety, while the spread vis-à-vis corresponding yields in other euro area countries widened significantly. At the same time, the oil price fell strongly, not only reflecting intensified concerns about the global growth implications of the spread of COVID-19 but also recent disagreements among the OPEC+ participants.

Given these developments, staff macroeconomic models have been used to provide mechanical estimates for the impact on growth and inflation from the changes in the oil price and exchange rate assumptions between the cut-off date for the technical assumptions of 18 February and 9 March (taking the average of the ten working days up to and including that date). The mechanical estimates presented below are provided as an indication of the order of magnitude with which more recent developments in the oil price and the exchange rate could affect the risks surrounding the projections. However, these mechanical estimates should not be interpreted as providing an alternative to the projections presented in the rest of this publication.

1) The mechanical impact of an updated path for oil prices

Oil price futures based on the ten working day average up to and including 9 March stood at USD 49.4 per barrel in the second quarter of 2020, which is 13.1% below the baseline assumption for that quarter. Thereafter, the oil price futures, as of 9 March 2020, entail a gradual increase to USD 52.7 per barrel in 2022, which is 5.2% below the baseline assumption for that year. Using the average of the results from staff macroeconomic models, this path would have a marginal upward impact on real GDP growth in 2020 and 2021, while HICP inflation would be 0.3 percentage points lower in 2020, slightly lower in 2021 and 0.1 percentage points higher in 2022.

2) The mechanical impact of an updated path for the exchange rate of the euro

As regards the euro exchange rate, the baseline assumes an exchange rate of USD 1.09 per euro. The average exchange rate of the ten working days up to and including 9 March was USD 1.11 per euro, which is 1.7% above the baseline assumption. The euro appreciated also against other major currencies, implying that the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro rose by 2.0% since the cut-off date for the baseline. Using the average of the results from staff macroeconomic models, real GDP growth would be dampened by about 0.1 percentage points in both 2020 and 2021, while HICP inflation would be 0.1 percentage point lower in 2020 to 2022.

Growth in housing investment is expected to continue, albeit at a more moderate pace. In the short term, an expected adverse impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on confidence, coupled with a slowdown in the number of building permits granted, suggest a moderating expansion of housing investment over the next few quarters. Housing investment growth is projected to remain moderate in 2021-22, as adverse demographic trends in some countries are expected to dampen housing investment.

Business investment is expected to remain subdued in the short term, before gradually gathering pace over the projection horizon. Business investment will be muted in the first half of 2020. Adverse cyclical effects associated with weak external demand, elevated policy uncertainty mainly in the export-oriented manufacturing sector and the adverse impact of the COVID-19 outbreak are expected to result in a significantly muted growth rate for business investment in 2020, implying a notable downward revision compared with the December 2019 projections. Beyond 2020, however, as uncertainty is assumed to dissipate, a number of favourable fundamentals are expected to support business investment. First, as economic activity recovers, firms will strengthen their investment so that their productive capital stock expands and catches up with demand. Second, financing conditions are expected to remain very supportive over the projection horizon. Third, profit margins are expected to improve, which should support investment growth. Finally, the leverage ratio of non-financial corporations (NFCs) has declined over recent years and NFCs’ gross interest payments have declined to record low levels.

Box 2

The international environment

The international projections were finalised on 18 February, prior to the global spread of COVID-19 beyond China and the subsequent reaction of financial markets. This box first describes the international projections included in the baseline. It then discusses the more recent developments since this cut-off date and their possible implications.

a) The global outlook (with a cut-off date of 18 February)

In 2019, global real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) declined to 2.9%, its slowest pace since the Great Recession. This slowdown was rather broad-based as global manufacturing output declined markedly amid increasing global uncertainty arising from the recurrent escalation of trade tensions, which led firms to postpone investment and consumers to delay purchases of durable goods. In addition, several emerging economies were hit by idiosyncratic shocks, which further accentuated decelerating global activity last year. At the same time, a number of key advanced and emerging economies deployed demand-stimulating policies, thereby limiting the pace and depth of the global growth slowdown.

The slowdown in global trade was even more pronounced. Annual growth of global imports (excluding the euro area) fell to 0.3% in 2019, significantly below the figure of 4.6% recorded in the previous year. A confluence of negative factors shaped these developments, including the rise in protectionism – raising trade uncertainty – and a turn in the global tech cycle, which weighed especially on those Asian economies closely integrated through supply chains.

At the turn of the year, signs of stabilisation in activity and trade had emerged. The projected bottoming out of global activity in the third quarter of 2019 was broadly confirmed by the data. Information available for the fourth quarter provided further support that global activity had been stabilising at rather subdued levels, as embedded in the December 2019 projections. However, growth in global imports and euro area foreign demand turned out to be much stronger in the second half of 2019 than expected in the December 2019 projections, owing largely to buoyant import growth in key emerging market economies, particularly China and Turkey. Survey data, available at the time when the projections were prepared, provided further evidence of a bottoming out of global activity, as the global composite output Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) (excluding the euro area) rose in January 2020, supported by better readings for both the manufacturing sector and the services sector. Moreover, the conclusion of the “Phase-one” trade agreement between the United States and China provided some respite from trade tensions, as both countries reduced tariffs on their bilateral trade and China committed to purchasing a substantial value of goods and services from the United States over the next two years. This partial de-escalation also supported equity prices, which also contributed to more favourable financing conditions in advanced economies and emerging markets.

The global outlook baseline, finalised on 18 February, had asserted that the COVID-19 outbreak would lead to a modest delay in the recovery in global activity. At the time of the cut-off date for the March 2020 projections for the international environment, on 18 February 2020, the baseline assumed that the prevailing outbreak would shave 1.5 percentage points off quarterly real GDP growth in China in the first quarter of 2020, followed by a rebound in the second and third quarters, as production was expected to return to normal levels. These projections were based on the assumption made at the time, namely that the COVID-19 outbreak would be largely confined to China, and that the rapidly falling new infection rates suggested only temporary – albeit significant – disruptions to economic activity in China.

The global recovery is expected to gain only modest traction. Growth in global activity (excluding the euro area) is projected to be 3.1% this year, slightly above an estimated 2.9% for 2019. Over the medium term, global growth is projected to increase slightly to 3.5% and 3.4% in 2021 and 2022 respectively, but to remain below its long-term average of 3.8%. The medium-term gradual pick-up in global growth hinges on the projected recovery in a number of emerging economies, which are expected to gradually recover from recent recessions or sharp growth slowdowns. However, the recovery path for this group of emerging market economies remains fragile amid external headwinds, which together with domestic political instability could derail the recovery prospects.

The international environment

(annual percentage changes)

1) Calculated as a weighted average of imports.

2) Calculated as a weighted average of imports of euro area trading partners.

The global medium-term trade outlook remains subdued by historical standards, as the trade elasticity of income is expected to remain below its “new normal” of unity.[3] This reflects a confluence of factors, including higher tariff rates than those enacted to date and elevated policy uncertainty. Global (excluding the euro area) import growth is expected to pick up gradually from 0.3% in 2019 to 1.4% in 2020, before accelerating to 2.6% and 2.7% in 2021 and 2022 respectively. Euro area foreign demand is projected to increase by 1.6% this year, before accelerating to 2.5% and 2.6% in 2021 and 2022 respectively. Compared with the December 2019 projections, euro area foreign demand has been revised upwards for 2020. However, this revision relates mainly to the statistical carry over effects of upside data surprises in the second half of 2019 and, to a limited extent, higher bilateral imports by the United States and China resulting from lower tariffs implemented in the context of the “Phase-one” trade deal. As the trade deal mostly supports bilateral trade between the two countries, however, benefits for euro area exports are likely to be limited; in fact, trade diversion effects may even weigh on euro area exports. Looking beyond the impact of these factors, the projected euro area foreign demand remains broadly unchanged from the December 2019 projections.

b) Developments regarding the global COVID-19 outbreak since the cut-off date for the finalisation of the global projections

The COVID-19 outbreak is still unfolding and its geographical and economic impact is evolving rapidly. While, as explained above, at the time of the cut-off date for the international projections on 18 February 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak was seen as largely being confined to mainland China, over the following weeks, it became clear that pronounced downside risks associated with the length, severity and geographical dispersion of the unfolding pandemic had already started to materialise.

Recent incoming data on China signal notable downside risks to the projections for the activity and trade of this country. The National Bureau of Statistics manufacturing headline PMI for China fell sharply to 35.7 in February, from 50.0 in the previous month, which represents the largest monthly decline since the start of the survey in 2005. Moreover, the business activity PMI in the non-manufacturing sector declined from 54.1 in January to 29.6 in February, a level far below that recorded during the Great Recession. These PMI readings signal sharp contractions across broad segments of China’s economy. In part, this is driven by the extension of business closures after the Chinese New Year in early February and restrictions on travel and transportation across China’s provinces. While in many regions of China business operations were allowed to resume over the course of February, logistical and operational difficulties have delayed the normalisation of production levels. These production delays, if protracted, will induce risks of disruption in global supply chains. High frequency indicators, such as the daily coal consumption of major electricity producers and data on traffic congestion, among others, suggest that in early March economic activity remained significantly below comparable levels in previous years. Overall, for the first quarter, the evidence points to an economic impact of COVID-19 on China that was more severe and more persistent than anticipated in the March 2020 baseline at the cut-off date for the international projections on 18 February. Finally, lower domestic demand in China also has adverse repercussions on its trading partners.

Since late February, the COVID-19 outbreak has spread significantly outside China. By early March, the virus had spread to over 80 countries. Geographically dispersed countries such as South Korea, Iran and Italy each faced significant independent outbreaks. An increasing number of countries are taking strict measures to contain the spreading of the virus, which will have a significant impact on activity in these countries, and possible knock-on effects on global value chains. At the same time, economic policy measures are increasingly being taken to compensate for the adverse impact of the pandemic on growth, including monetary policy easing by the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England.

Overall, the more adverse and more lasting than envisaged impact of COVID-19 in China and a much faster spreading of the virus globally clearly point to downside risks to the projections for the global outlook. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on global activity and trade is significantly more adverse than anticipated in mid-February. This deterioration in the global and trade outlook has been partially reflected in the baseline for the euro area, via judgement.

Euro area export growth is projected to remain subdued in the first half of 2020 and to strengthen gradually over the rest of the projection horizon. Export growth is projected to be particularly weak in the first half of 2020, as a result of waning demand in China and other Asian economies, as well as supply side disruptions triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak. Apart from the direct impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on travel and transport services, trade is also expected to be affected by domestic and international supply chain disruptions. A recovery in trade is projected in the second half of this year and the pace of expansion of exports will improve in line with the path of foreign demand (see Box 2), implying broadly stable export market shares over the projection horizon. Overall, the contribution of net trade to real GDP growth is projected to be broadly neutral over the projection horizon.

Employment growth is projected to be subdued in the course of 2020, largely reflecting the notably weak activity in the short term. Employment growth will recover in the course of 2021 as activity gains momentum. Over the medium term, employment growth in the euro area is projected to remain muted, as labour supply is expected to limit employment expansion.

Growth in the labour force is expected to moderate over the projection horizon. The labour force is expected to continue to expand, reflecting the projected net immigration of workers (including the expected integration of refugees) and ongoing increases in the participation rate. Nevertheless, these factors are projected to fade over the projection horizon and the adverse impact of population ageing on labour force growth is expected to increase, as older cohorts leave the workforce in higher numbers than younger cohorts enter it.

The unemployment rate is expected to rise slightly in the course of 2020 and then be broadly stable over the remainder of the projection horizon at around 7½%. Heterogeneity in labour markets will continue to persist as unemployment rates are expected to continue to exhibit substantial differences in 2022 across euro area countries.

Labour productivity growth is projected to recover over the projection horizon. With the COVID-19 outbreak expected to adversely affect growth more than employment, labour productivity should be very subdued in the first half of 2020. Over the rest of the horizon, productivity growth is expected to pick up as activity regains momentum, while labour input growth is expected to slow. In 2022 growth in labour productivity per person employed should slightly exceed its pre-crisis average of 1.0.[4]

Compared with the December 2019 projections, real GDP growth has been revised down by 0.3 percentage points for 2020 and 0.1 percentage points for 2021. The downward revision to activity for 2020 reflects a small carry-over effect from the weaker than expected outturn for growth in the fourth quarter of 2019, a more prolonged than previously expected weakness in the manufacturing sector and, notably, the expected adverse impact of the COVID-19 outbreak. Lower growth in 2020 implies some negative carry-over to 2021.

Box 3

Scenario: Impacts on the euro area economy from an intensification of the COVID-19 pandemic, both globally and within the euro area

In the context of the high uncertainty surrounding the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, this box presents two scenarios in case of an intensification of the crisis beyond what is contained in the current baseline. The first “mild” scenario considers the implications of a more persistent COVID-19 outbreak for China and the euro area. The second “severe” scenario builds on the first, with some additional shocks to financial markets and oil prices. Both scenarios are evaluated using two core ECB macroeconomic models.[5]

In both scenarios, the epidemic in China extends into the second quarter of 2020. Consequently, the recovery is delayed to the second half of the year, giving rise to notable global supply chain disruptions. This contrasts with the baseline for China, in which it is assumed that the outbreak peaks in the first quarter of 2020, such that the decline in economic growth is concentrated in the first quarter of 2020 and the economy recovers from the second quarter onwards. The scenario also entails notably lower imports than assumed in the baseline for the first quarter of 2020. Moreover, the supply chain disruptions lead to an additional supply shock in China which increases CPI headline inflation. It is also assumed that the prolonged effort to contain the epidemic has adverse effects on confidence, increases uncertainty and results in a hike in the risk premia in China. Overall, the weaker global outlook for China and for other global economies implies lower euro area foreign demand (by 0.3% in 2020) and lower oil prices (by 14%).

In addition, in both scenarios, the spread of COVID-19 in the euro area is assumed to widen significantly. To capture this, a number of specific adverse shocks have been assumed for the euro area. Financial markets react negatively to the deterioration of the situation, causing a sudden increase in risk premia (by 20 basis points), adversely affecting the financing conditions of firms and households. A supply-side shock reflects potential supply-chain disruptions. In addition, shocks have been applied to reflect the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on euro area employment, tourism and travel expenditure, as well as on the consumption of transport and recreational and cultural services.

In the severe scenario, additional financial shocks are added together with a further decline in the oil price. The severe scenario includes the same shocks as in the mild scenario, but these are supplemented with an additional increase in credit spreads (by 80 basis points in 2020), a 10% decline in both equity prices and housing wealth and an additional fall in oil prices (by 20%).

Under the mild scenario, compared to the March 2020 projections, the negative impact on euro area GDP growth would be between 0.6 percentage points and 0.8 percentage points in 2020. The impact on inflation would be lower by around 0.2 percentage points, as downside impacts stemming primarily from declines in oil prices are partially offset by the upward impact from supply-side shocks.

Under the severe scenario, compared to the March 2020 projections, the negative impact on euro area GDP growth would be between 0.8 percentage points and 1.4 percentage points in 2020, while inflation would be between 0.4 percentage points and 0.8 percentage points lower in the same year. The further weakening in real economic activity in this scenario is mainly driven by the strong widening of credit spreads and the deterioration in financial wealth. While the assumed heightened financial stress has only marginal effects on inflation, its drop largely reflects the strong permanent fall in the oil price.

It should be noted that in both scenarios, monetary and fiscal policy do not react. Including such policy reactions could significantly mitigate the effects in both scenarios.

2 Prices and costs

HICP inflation is expected to decrease slightly from 1.2% in 2019 to 1.1% in 2020, reflecting dampening effects from energy prices, and to pick up gradually thereafter to 1.6% by 2022 (see Chart 2). The weaker headline inflation rate in 2020, compared with 2019, reflects a notable drop in HICP energy prices given weak developments in oil prices (up to the time of the cut-off date for the technical assumptions), partly on account of the COVID-19 outbreak. HICP energy inflation is expected to remain negative throughout the year and to turn positive only in the second quarter of 2021, as the oil price futures curve flattens and also in view of some upward effects from energy-related indirect tax increases. While the impact of the weaker demand outlook related to the COVID-19 outbreak should also put downward pressure on non-energy prices, this is expected to be largely offset by upward effects related to supply disruptions. Developments in food commodity prices are assumed to continue to contribute to HICP food inflation, but the effect gradually decreases over the projection horizon, implying a slightly declining profile for HICP food inflation starting in mid-2020. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to hover around 1.2-1.3% in the course of 2020 and to strengthen gradually to 1.4% in 2021 and 1.5% in 2022. On the domestic side, the envisaged recovery in activity is expected to support the strengthening in HICP inflation excluding energy and food over the projection horizon. The pick-up in this measure of inflation will also be supported by relatively robust wage growth and a recovery in profit margins. On the external side, rising non-energy commodity prices and import prices should contribute to the envisaged strengthening in HICP inflation excluding energy and food over the projection horizon.

Chart 2

Euro area HICP

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Notes: The ranges shown around the central projections are based on the differences between actual outcomes and previous projections carried out over a number of years. The width of the ranges is twice the average absolute value of these differences. The method used for calculating the ranges, involving a correction for exceptional events, is documented in “New procedure for constructing Eurosystem and ECB staff projection ranges”, ECB, December 2009, available on the ECB’s website.

Growth in compensation per employee is projected to moderate in 2020 and to pick up in 2021 and 2022, as activity gathers pace and labour markets remain tight. Growth in compensation per employee was dampened in 2019 by the impact of the conversion of a tax credit into a permanent cut to employers’ social security contributions in France (CICE[6]). The slowdown in economic activity also contributed to the weakening in compensation per employee growth in the course of 2019. While the weaker economic developments are seen as continuing to weigh on growth in compensation per employee in 2020, the rebound in economic activity and continued tight labour markets are expected to contribute to higher compensation per employee growth in 2021 and 2022.

Growth in unit labour costs is projected to decrease until the beginning of 2021 and to strengthen slightly over the remainder of the projection horizon. The declining profile in unit labour cost growth until the beginning of 2021 is explained by the weakening in compensation per employee growth combined with the envisaged strengthening in labour productivity growth, as GDP growth gradually strengthens. Thereafter the broadly flat developments in labour productivity growth, together with the envisaged increases in compensation per employee growth, imply a slight strengthening in unit labour cost growth in the course of 2021 and 2022.

Having been squeezed over the past two years, profit margins are expected to recover slightly in 2021 and 2022. The cyclical weakening in economic activity, the increase in wage growth and the stronger oil price developments in 2018 weighed on profit margin developments over the past two years. Improvements in domestic and foreign demand are envisaged to support profit margins in 2021 and 2022.

External price pressures are expected to be weak in 2020 and strengthen thereafter. This profile in import price developments is strongly affected by movements in oil prices, with the slope of the oil price futures curve implying a larger negative growth rate in 2020 but smaller negative rates in 2021 and 2022. The positive import price inflation rate over the projection horizon reflects also upward price pressures from both non-oil commodity prices and underlying global price developments more generally.

Compared with the December 2019 projection, the outlook for HICP inflation is unrevised over the projection horizon. Downward effects on headline inflation in 2020 from lower oil price assumptions are broadly offset by higher food commodity price assumptions. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is broadly unrevised in 2020, as the impact of weaker demand is largely offset by some expected upward impacts on prices due to supply side disruptions from the spread of COVID-19. For the remainder of the horizon, inflation is unrevised.

3 Fiscal outlook

The euro area fiscal stance[7] is assessed to be expansionary over 2020-21 and broadly neutral in 2022. The projected loosening of the fiscal stance over 2020-21 stems mostly from higher spending, in particular transfers, as well as from cuts in direct taxes and social security contributions. In 2022 the fiscal stance is projected to be broadly neutral. Compared with the December 2019 projections, the fiscal stance is expected to be marginally more expansionary in 2020 and 2021.[8]

The euro area budget balance is projected to decline steadily over 2020-21 and to stabilise in 2022, while the debt ratio remains on a downward path. The decline in the budget balance stems from the expansionary fiscal stance. This is partly compensated for by lower interest expenditure, while the positive contribution of the cyclical component to the budget balance declines in 2020-21. The favourable dynamics of the government debt ratio over the projection horizon are driven by the favourable interest rate-growth differential. By contrast, the support from the primary balance fades away in 2021-22, when it is projected to turn negative.

The March 2020 fiscal projections show higher budget deficits in 2020-22 than the equivalent projections in the December 2019 exercise. While the assessment of the budget balance for 2019 remains unchanged, for the period 2020-22 the balance is expected to be noticeably lower than entailed in the December 2019 projection exercise, owing to a stronger decline in the primary balance. From a surplus of 0.9% of GDP estimated for 2019, the euro area primary balance is projected to register a small deficit in 2021 and 2022, while in the previous exercise there was still a small surplus until the end of the projection horizon. This revision is due both to a slightly more expansionary stance and to a worsening of the cyclical component. The debt ratio is projected to be on a higher path than in the December 2019 projections, also owing to the lower primary balance.

Box 4

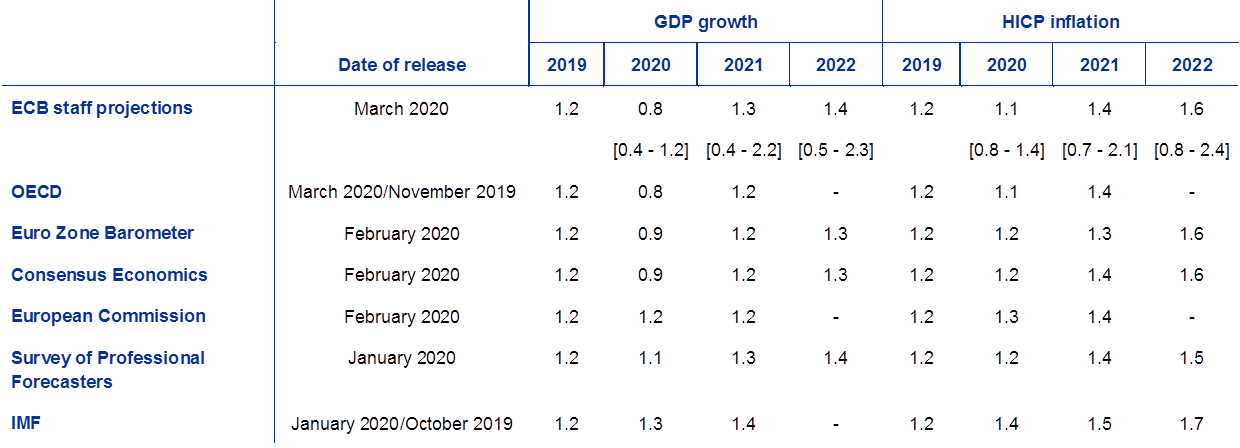

Forecasts by other institutions

A number of forecasts for the euro area are available from both international organisations and private sector institutions. However, these forecasts are not strictly comparable with one another or with the ECB staff macroeconomic projections, as they were finalised at different points in time. They are also based on different assumptions about the likely spread of the COVID-19 virus. Additionally, these projections use different (partly unspecified) methods to derive assumptions for fiscal, financial and external variables, including oil and other commodity prices. Finally, there are differences in working day adjustment methods across different forecasts (see the table).

The staff projections for real GDP growth and HICP inflation are broadly within the range of forecasts from other institutions and private sector forecasters. The projections for growth and inflation for 2020 are lower than those of other forecasters, with the exception of the OECD, which is the only institution to have published an update (for real GDP growth) after the outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy (on 2 March).

Comparison of recent forecasts for euro area real GDP growth and HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: OECD Economic Outlook, November 2019 for the HICP and March 2020 for GDP; MJEconomics for the Euro Zone Barometer, February 2020; Consensus Economics Forecasts, February 2020; European Commission Economic Forecast, Winter 2020; ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters, 2020 Q1; IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2019 for the HICP and January 2020 for GDP.

Notes: The ECB staff macroeconomic projections and the OECD forecasts both report working day-adjusted annual growth rates, whereas the European Commission and the IMF report annual growth rates that are not adjusted for the number of working days per annum. Other forecasts do not specify whether they report working day-adjusted or non-working day-adjusted data.

© European Central Bank, 2020

Postal address 60640 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Website www.ecb.europa.eu

All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

For specific terminology please refer to the ECB glossary (available in English only).

PDF ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-20-001-EN-N

HTML ISSN 2529-4466, QB-CE-20-001-EN-Q

- The cut-off date for technical assumptions, such as for oil prices and exchange rates, was 18 February 2020 (see Box 1). The macroeconomic projections for the euro area were finalised on 28 February 2020.

The current macroeconomic projection exercise covers the period 2020-22. Projections over such a long horizon are subject to very high uncertainty, and this should be borne in mind when interpreting them. See the article entitled “An assessment of Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections” in the May 2013 issue of the ECB’s Monthly Bulletin. See http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/index.en.html for an accessible version of the data underlying selected tables and charts. - The assumption for euro area ten-year nominal government bond yields is based on the weighted average of countries’ ten-year benchmark bond yields, weighted by annual GDP figures and extended by the forward path derived from the ECB’s euro area all-bonds ten-year par yield, with the initial discrepancy between the two series kept constant over the projection horizon. The spreads between country-specific government bond yields and the corresponding euro area average are assumed to be constant over the projection horizon.

- See, for example, IRC Trade Task Force, “Understanding the weakness in global trade – What is the new normal?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 178, ECB, September 2016.

- The average between 1999 and 2007.

- See Coenen, G et al “The New Area-Wide Model II: an extended version of the ECB’s micro-founded model for forecasting and policy analysis with a financial sector”, ECB Working Paper No. 2200, November 2018 and Angelini, E. et al “Introducing ECB-BASE: The blueprint of the new ECB semi-structural model for the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No 2315, September 2019.

- As the CICE-related decrease in compensation per employee and unit labour costs is largely offset by a corresponding increase in profit margins, the impact on price setting is expected to be limited.

- The fiscal policy stance is measured as the change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance net of government support to the financial sector.

- The fiscal assumptions embedded in the March 2020 projections do not include measures in response to the COVID-19 outbreak that have been announced in Italy and several other euro area countries since 28 February.

- 12 March 2020